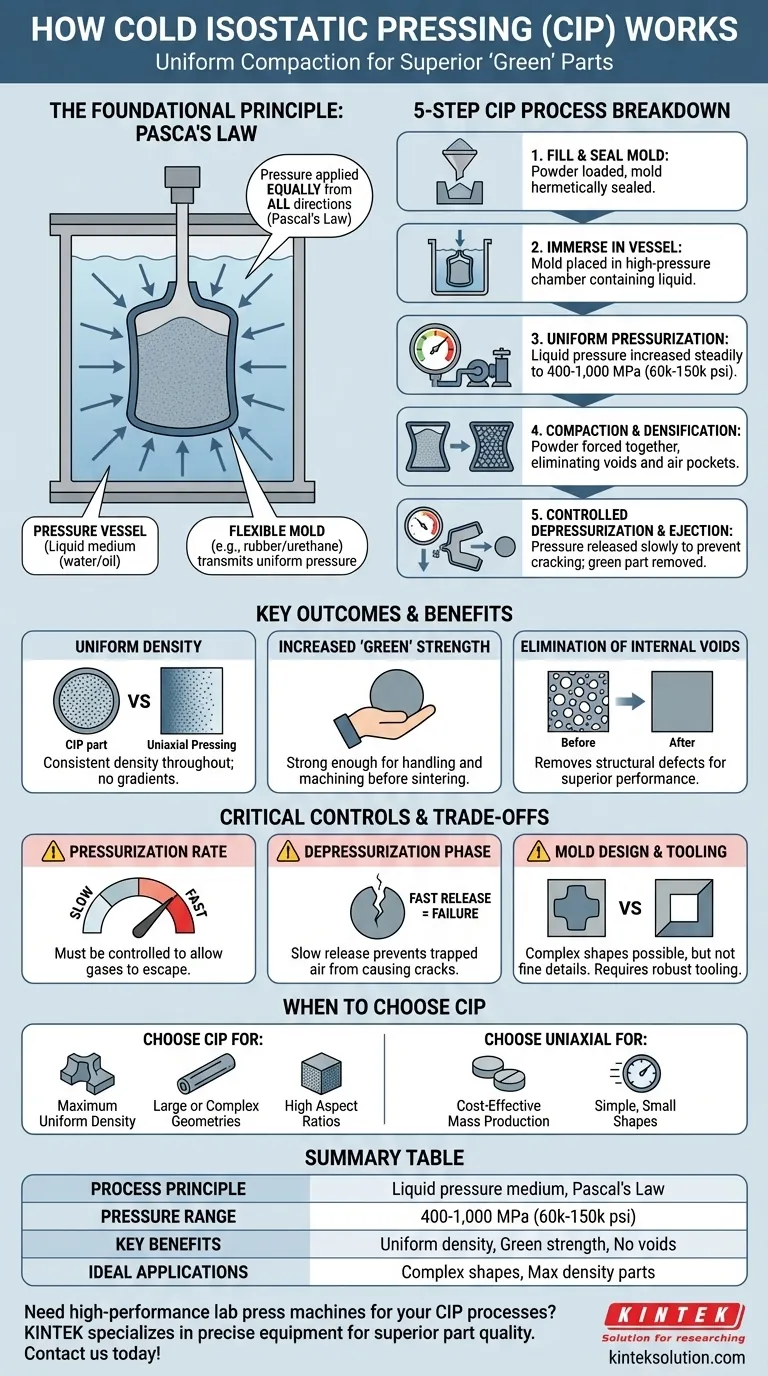

In essence, Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP) is a manufacturing method that uses a liquid to apply extreme, uniform pressure to a powdered material sealed inside a flexible mold. This process compacts the powder into a solid object with consistent density and improved strength before it undergoes final processing, like sintering. It is fundamentally different from traditional pressing, which applies force from only one or two directions.

The core principle of CIP is its use of a liquid pressure medium to exploit Pascal's Law. This ensures pressure is applied equally from all directions, eliminating the internal voids and density variations that plague other compaction methods and resulting in a superior, highly uniform "green" part.

The Foundational Principle: Why "Isostatic" Matters

To understand CIP, you must first understand the concept of "isostatic" pressure. It is the key differentiator and the source of the process's primary benefits.

Harnessing Pascal's Law

The process is built on Pascal's Law, a fundamental principle of fluid mechanics. This law states that pressure exerted on a confined, incompressible fluid is transmitted equally in all directions throughout the fluid.

By submerging the component in a liquid like water or oil within a sealed vessel, the applied pressure is not directional. It pushes inward on every single surface of the mold with identical force, which is impossible to achieve with a mechanical press.

The Role of the Flexible Mold

The powder is held within a sealed, flexible mold made of an elastomer like rubber, urethane, or PVC. This mold acts as the barrier between the powder and the pressure fluid.

Because the mold is flexible, it perfectly transmits the uniform hydraulic pressure from the liquid directly to the powder it contains, ensuring the powder itself is compacted isostatically.

A Step-by-Step Breakdown of the CIP Process

The CIP cycle is a controlled and precise sequence designed to transform loose powder into a dense solid.

Step 1: Mold Filling and Sealing

The process begins by filling the flexible mold with the desired powder. The mold defines the initial shape of the component. Once filled, it is hermetically sealed to prevent the pressurizing fluid from infiltrating the powder.

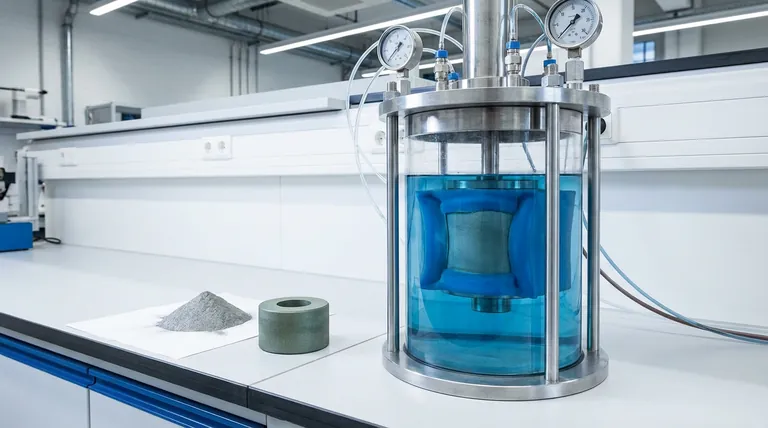

Step 2: Immersion in the Pressure Vessel

The sealed mold is then placed into the chamber of a high-pressure vessel. This chamber is filled with a liquid medium, typically water or a specialized oil, which will serve to transmit the pressure.

Step 3: Uniform Pressurization

The vessel is sealed, and pumps increase the pressure of the liquid to extreme levels, typically between 400 and 1,000 MPa (60,000 to 150,000 psi). The pressure is applied steadily to ensure it permeates the system evenly.

Step 4: Compaction and Densification

Under this immense, uniform pressure, the powder particles are forced together. Air pockets and voids between the particles collapse, and the material compacts into a solid form with a density approaching its theoretical maximum. The part is now referred to as a "green" compact.

Step 5: Controlled Depressurization and Ejection

After a set holding time, the pressure is slowly and carefully released. The mold, containing the newly densified part, is removed from the vessel. The part is then ejected from the mold, now strong enough for handling and subsequent manufacturing steps.

Key Outcomes: The Properties of a CIP'd Part

The unique nature of isostatic pressure yields parts with distinct advantages over those made with conventional pressing.

Uniform Density

Because pressure is applied from all sides, the resulting component has a highly uniform density throughout its structure. This is a critical advantage over uniaxial (single-direction) pressing, which often creates density gradients, with the areas farthest from the press punch being less dense.

Increased "Green" Strength

The interlocking of powder particles during compaction gives the "green" part significant mechanical strength. While not yet in its final, hardened state, it is robust enough to be handled, machined, or transported to the next stage, which is typically a high-temperature sintering furnace.

Elimination of Internal Voids

The primary mechanism of CIP is the elimination of porosity. By squeezing the material from every angle, the process effectively removes the voids that can become structural defects in the final product, leading to superior performance and reliability.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Critical Controls

While powerful, CIP is a technical process where control is paramount to success. Mismanagement of its variables can lead to failed parts.

The Importance of Pressurization Rate

Applying pressure too quickly can trap air within the powder, leading to defects or preventing full densification. A controlled, steady rate of pressurization is essential for allowing gases to escape and ensuring the part compacts uniformly.

The Critical Depressurization Phase

Releasing pressure too rapidly is a common cause of part failure. Any residual air trapped in the part's microscopic pores will be at extremely high pressure. A sudden drop in external pressure causes this trapped air to expand violently, which can cause cracks, delamination, or even catastrophic failure of the green part.

Mold Design and Tooling

The flexible molds allow for complex shapes but have limitations. They cannot easily produce sharp external corners or extremely fine details. Furthermore, the high pressures require robust and therefore expensive pressure vessels and tooling.

When to Choose Cold Isostatic Pressing

Deciding to use CIP depends entirely on the geometric complexity and performance requirements of your final component.

- If your primary focus is achieving maximum uniform density: CIP is the superior method, as it eliminates the density gradients inherent in uniaxial pressing.

- If your primary focus is producing large or complex shapes: CIP provides a significant advantage for parts with high aspect ratios (long and thin) or intricate geometries that are difficult or impossible to produce in a rigid die.

- If your primary focus is cost-effective mass production of simple shapes: Traditional uniaxial die pressing is often a more economical and faster choice for smaller, simpler components like tablets or bushings.

Ultimately, Cold Isostatic Pressing is an essential tool for creating high-performance material preforms where internal uniformity and structural integrity are paramount.

Summary Table:

| Key Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Process Principle | Uses liquid pressure medium and Pascal's Law for uniform compaction |

| Pressure Range | 400 to 1,000 MPa (60,000 to 150,000 psi) |

| Key Benefits | Uniform density, increased green strength, elimination of internal voids |

| Ideal Applications | Complex shapes, high aspect ratios, parts requiring maximum density |

| Critical Controls | Controlled pressurization and depressurization to prevent defects |

Need high-performance lab press machines for your CIP processes? KINTEK specializes in automatic lab presses, isostatic presses, heated lab presses, and more to meet your laboratory needs. Our equipment ensures precise pressure control and uniform compaction for superior part quality. Contact us today to discuss how we can enhance your material processing and boost efficiency!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electric Lab Cold Isostatic Press CIP Machine

- Electric Split Lab Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine

- Automatic Lab Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine

- Manual Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine Pellet Press

- Lab Polygon Press Mold

People Also Ask

- What are the technical advantages of using a cold isostatic press (CIP) for electrolyte powders?

- What advantages does electrical Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP) have over manual CIP? Boost Efficiency and Consistency

- What is the specific function of a Cold Isostatic Press (CIP)? Enhance Carbon Inoculation in Mg-Al Alloys

- How does the dry bag process in Cold Isostatic Pressing work? Speed Up Your High-Volume Powder Compaction

- Why is Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP) preferred over simple uniaxial pressing for zirconia? Achieve Uniform Density.