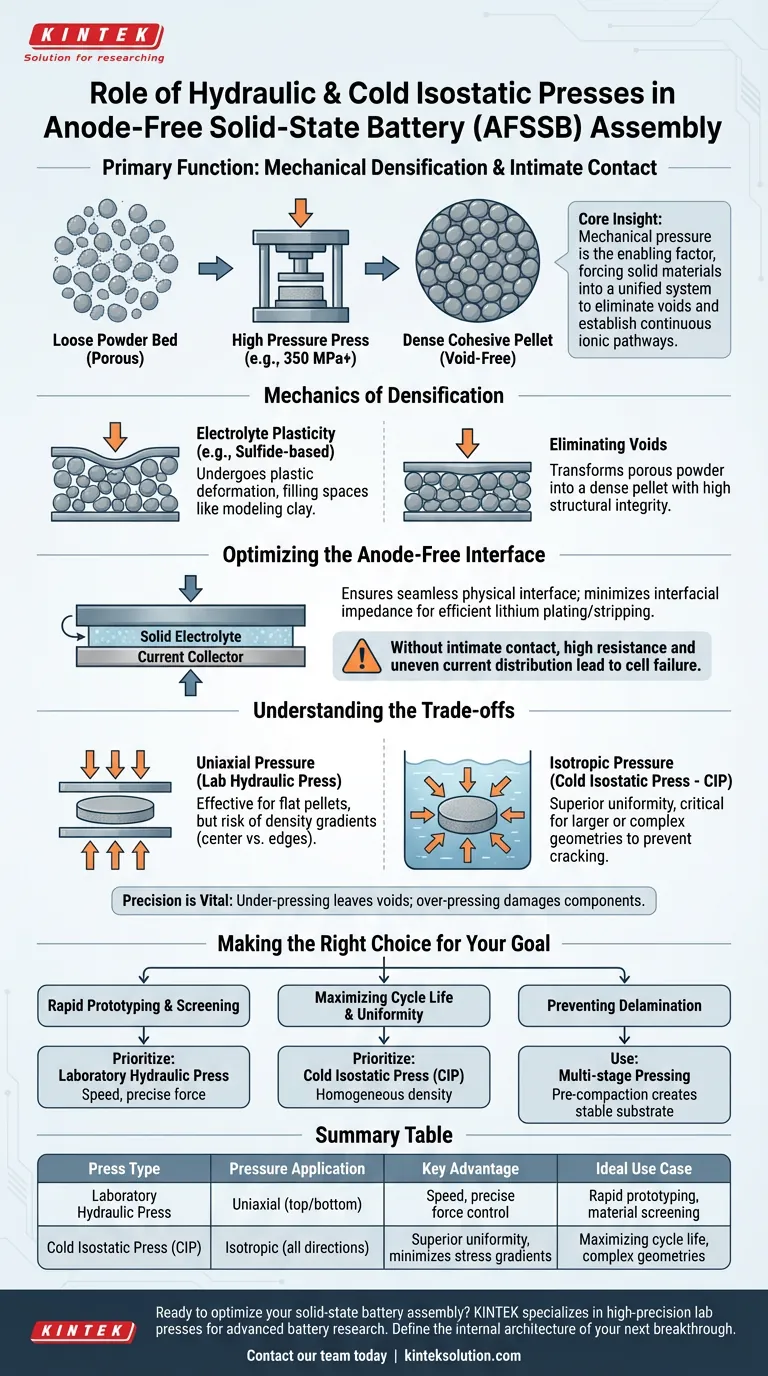

The primary function of a laboratory hydraulic press or cold isostatic press in assembling anode-free solid-state batteries (AFSSBs) is to mechanically densify the solid electrolyte through plastic deformation and establish intimate, void-free contact between the cell layers. By applying high pressure (often several hundred MPa) at room temperature, these presses eliminate porosity and reduce interfacial resistance, creating the continuous physical pathway necessary for ionic transport.

Core Insight: In the absence of liquid electrolytes to "wet" the components, mechanical pressure becomes the enabling factor for battery chemistry. It forces solid materials to behave like a unified system, minimizing the impedance that otherwise prevents the efficient plating and stripping of lithium on the current collector.

The Mechanics of Densification

The central challenge in solid-state battery assembly is ensuring that solid particles touch each other sufficiently to allow ions to pass.

Leveraging Electrolyte Plasticity

Certain solid electrolytes, particularly sulfide-based materials, possess unique ductility at room temperature.

When compressed by a hydraulic press, these materials undergo plastic deformation. They do not merely pack together; they physically deform to fill spaces, much like modeling clay.

Eliminating Voids

A loose powder bed is full of microscopic gaps (voids) that block ion movement.

The application of high pressure—such as 350 MPa or higher—collapses these voids. This transforms a porous powder into a dense, cohesive pellet with high structural integrity.

Optimizing the Anode-Free Interface

In an anode-free architecture, there is no pre-existing lithium anode; lithium must plate directly onto the current collector.

Ensuring Critical Contact

The press ensures a seamless physical interface between the solid electrolyte and the current collector.

Without this "intimate contact," the connection is spotty. This leads to high resistance and uneven current distribution, which ruins the battery's ability to cycle.

Minimizing Interfacial Impedance

High-quality physical contact correlates directly with low interfacial impedance.

By removing the physical gaps between layers, the press lowers the barrier for charge transfer. This allows for stable electrochemical measurements and efficient lithium deposition.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While pressure is essential, how it is applied matters immensely.

Uniaxial vs. Isotropic Pressure

A standard laboratory hydraulic press applies uniaxial pressure (from top and bottom). While effective for flat pellets, it can sometimes create density gradients where the center is denser than the edges.

A Cold Isostatic Press (CIP) applies pressure from all directions (isotropically). This ensures superior uniformity throughout the electrolyte body, which is critical for larger or complex cell geometries to prevent cracking.

The Risk of Over- or Under-Pressing

Insufficient pressure leaves voids, creating "dead spots" where ions cannot travel, leading to immediate cell failure.

Conversely, excessive or uneven pressure can damage delicate separators or cathode composites. Precision in applying force (e.g., exact tonnage control) is vital to avoid crushing the structural integrity of the cell components.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The choice between pressing methods and pressure levels depends on your specific experimental targets.

- If your primary focus is rapid prototyping and material screening: Prioritize a Laboratory Hydraulic Press for its speed and ability to apply precise, uniaxial force to standard coin or pellet cells.

- If your primary focus is maximizing cycle life and pellet uniformity: Prioritize a Cold Isostatic Press (CIP) to achieve homogeneous density and minimize internal stress gradients within the electrolyte layer.

- If your primary focus is preventing delamination: Use multi-stage pressing, applying a pre-compaction pressure to the first layer to create a stable substrate before adding and pressing subsequent layers.

Ultimately, the press is not just an assembly tool; it is a parameter that defines the internal architecture and electrochemical efficiency of your final battery cell.

Summary Table:

| Press Type | Pressure Application | Key Advantage | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Hydraulic Press | Uniaxial (top/bottom) | Speed, precise force control | Rapid prototyping, material screening |

| Cold Isostatic Press (CIP) | Isotropic (all directions) | Superior uniformity, minimizes stress gradients | Maximizing cycle life, complex geometries |

Ready to optimize your solid-state battery assembly? The precision and uniformity of your pressing process are critical to achieving low interfacial resistance and long cycle life. KINTEK specializes in lab press machines, including automatic lab presses, isostatic presses, and heated lab presses, designed to meet the exacting demands of advanced battery research. Let our expertise help you define the internal architecture of your next breakthrough. Contact our team today to discuss your specific application requirements!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic Lab Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine

- Electric Lab Cold Isostatic Press CIP Machine

- Electric Split Lab Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine

- Lab Isostatic Pressing Molds for Isostatic Molding

- Manual Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine Pellet Press

People Also Ask

- Why is a cold isostatic press (CIP) required for the secondary pressing of 5Y zirconia blocks? Ensure Structural Integrity

- Why is Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP) used for copper-CNT composites? Unlock Maximum Density and Structural Integrity

- Why is a Cold Isostatic Press (CIP) necessary for Silicon Carbide? Ensure Uniform Density & Prevent Sintering Cracks

- Why is a Cold Isostatic Press (CIP) required for Al2O3-Y2O3 ceramics? Achieve Superior Structural Integrity

- What are the typical operating conditions for Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP)? Master High-Density Material Compaction