At its core, Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique used to identify chemical substances. It works by passing infrared light through a sample and measuring which specific frequencies of light are absorbed, creating a unique spectral "fingerprint" for the molecules within it.

Identifying the composition of an unknown material can be a critical challenge. FTIR spectroscopy solves this by rapidly and non-destructively revealing the chemical bonds—the fundamental building blocks—present in a sample, thereby determining its molecular identity.

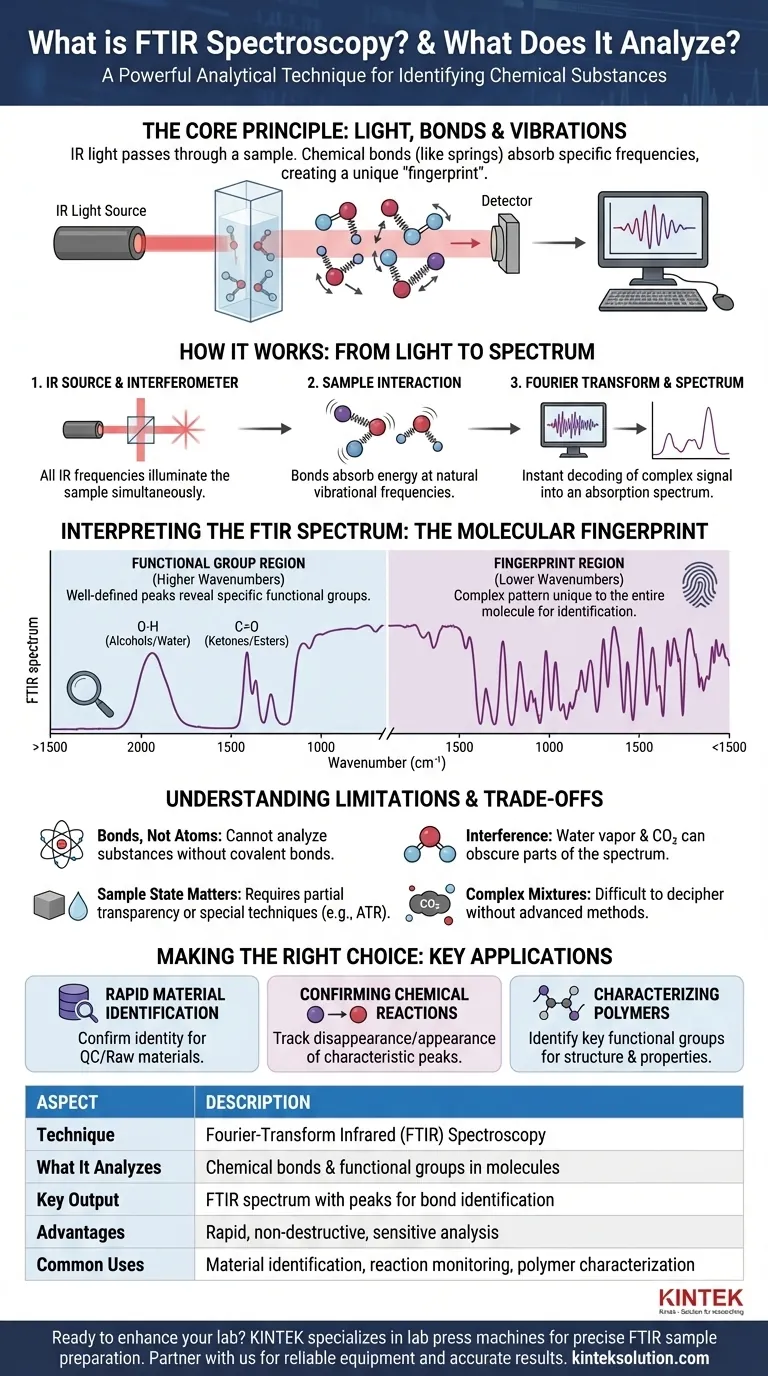

How FTIR Works: From Light to Spectrum

To understand what FTIR analyzes, you must first understand its mechanism. The process translates the interaction between light and matter into a detailed chemical map.

The Role of Infrared Light

The key to the technique is the use of infrared (IR) light. This region of the electromagnetic spectrum has the perfect amount of energy to excite the natural vibrations of chemical bonds in most molecules.

Molecular Vibrations: Bonds as Springs

Imagine the chemical bonds between atoms as tiny springs. Just as different springs have different stiffnesses, different types of chemical bonds (like a carbon-oxygen double bond, C=O, or an oxygen-hydrogen single bond, O-H) vibrate at their own characteristic frequencies.

When IR light with a frequency that exactly matches a bond's natural vibrational frequency hits the molecule, the bond absorbs that energy.

From Absorption to a Spectrum

An FTIR spectrometer measures this absorption. It plots the amount of light absorbed versus the frequency (or wavenumber) of the light.

The result is an FTIR spectrum: a graph with distinct peaks. Each peak corresponds to a specific type of chemical bond that absorbed the IR light, revealing the functional groups present in the sample.

The "Fourier-Transform" Advantage

Modern instruments use a mathematical method called a Fourier Transform. Instead of scanning one frequency at a time, the spectrometer shines all IR frequencies on the sample simultaneously. The resulting complex signal is then instantly decoded by the Fourier Transform into the familiar absorption spectrum. This makes the analysis incredibly fast and sensitive.

Interpreting an FTIR Spectrum: The Molecular Fingerprint

An FTIR spectrum provides two critical layers of information for chemical identification. It is often split into two main areas for analysis.

The Functional Group Region

Typically found at higher wavenumbers (above 1500 cm⁻¹), this region contains clear, well-defined peaks that correspond to specific functional groups.

For example, a strong, broad peak around 3300 cm⁻¹ is a classic indicator of an O-H group (found in alcohols and water), while a sharp, intense peak near 1700 cm⁻¹ signals a C=O group (found in ketones, aldehydes, and esters). This allows an analyst to deduce parts of the molecule's structure.

The Fingerprint Region

The area at lower wavenumbers (below 1500 cm⁻¹) is known as the fingerprint region. The combination of many single-bond vibrations here creates a complex pattern of peaks that is unique to the molecule as a whole.

While difficult to interpret peak by peak, this region is extremely powerful for identification. By comparing a sample's fingerprint region to a database of known spectra, you can confirm its identity with very high confidence.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Limitations

While powerful, FTIR is not a universal solution. Understanding its limitations is crucial for proper application.

It Identifies Bonds, Not Atoms

FTIR sees the bonds between atoms (C-H, N-O, etc.), not the individual atoms themselves. Therefore, it cannot analyze substances without covalent bonds that vibrate, such as individual atoms (e.g., Argon) or simple ionic salts (e.g., NaCl).

Sample State Matters

The sample must be at least partially transparent to IR light for a measurement to occur. This can make analyzing very thick or highly absorbing materials difficult without special techniques like Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR), which allows for the analysis of solid and liquid surfaces.

Water and CO₂ Can Interfere

Water vapor and carbon dioxide are naturally present in the atmosphere, and both absorb IR light strongly. This can obscure parts of the sample's spectrum. A "background" spectrum is always collected and subtracted to minimize this interference.

Poorly Suited for Complex Mixtures

While FTIR excels at identifying pure substances or simple mixtures, analyzing a complex mixture with many components is challenging. The individual spectra overlap, creating a convoluted result that is difficult to decipher without advanced statistical methods.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

FTIR is a versatile tool, but its application depends on your analytical objective.

- If your primary focus is rapid material identification: Use FTIR to match a sample's "fingerprint" against a spectral library to confirm identity, often for quality control or verifying raw materials.

- If your primary focus is confirming a chemical reaction: Use FTIR to track the disappearance of a reactant's characteristic peaks and the appearance of new peaks corresponding to the product's functional groups.

- If your primary focus is characterizing a polymer or organic compound: Use FTIR as a primary screening tool to identify the key functional groups present, which provides critical clues about the material's structure and properties.

Ultimately, FTIR spectroscopy empowers you to translate the invisible vibrations of molecules into a clear, actionable chemical signature.

Summary Table:

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Technique | Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy |

| What It Analyzes | Chemical bonds and functional groups in molecules |

| Key Output | FTIR spectrum with peaks for bond identification |

| Advantages | Rapid, non-destructive, sensitive analysis |

| Limitations | Cannot analyze atoms without covalent bonds; sensitive to sample state and interference |

| Common Uses | Material identification, reaction monitoring, polymer characterization |

Ready to enhance your laboratory's analytical capabilities? KINTEK specializes in lab press machines, including automatic lab presses, isostatic presses, and heated lab presses, designed to support precise sample preparation for techniques like FTIR spectroscopy. By partnering with us, you'll benefit from reliable equipment that ensures accurate results, improves efficiency, and meets diverse lab needs. Contact us today to discuss how our solutions can drive your research forward!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Lab Infrared Press Mold for Laboratory Applications

- Lab Infrared Press Mold for No Demolding

- Lab XRF Boric Acid Powder Pellet Pressing Mold for Laboratory Use

- Square Lab Press Mold for Laboratory Use

- Manual Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine Pellet Press

People Also Ask

- What technical factors are considered when selecting precision stainless steel molds? Optimize Fluoride Powder Forming

- Why are precision laboratory molds essential for forming basalt-reinforced lightweight concrete specimens?

- How does a prismatic composite mold ensure the quality consistency of pressed briquettes? Precision Molding Solutions

- How do high-hardness precision molds affect NiO nanoparticle electrical testing? Ensure Accurate Material Geometry

- Why is a tungsten carbide (WC) die required for hot-pressing all-solid-state battery stacks? Ensure Viable Densification