Applying 50 MPa of pressure serves as the critical mechanical driving force required to transform loose LLZTO powder into a solid, high-density electrolyte. This uniaxial force physically compresses the powder particles, inducing rearrangement and plastic deformation to mechanically close the gaps between them. By acting simultaneously with the rapid heating of the Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) process, this pressure accelerates densification and ensures the final ceramic is free of microscopic voids.

The Core Insight Heat alone is often insufficient to create a structurally sound solid-state electrolyte. The application of 50 MPa pressure is the deciding factor that eliminates porosity, creating the dense physical barrier necessary to prevent battery failure.

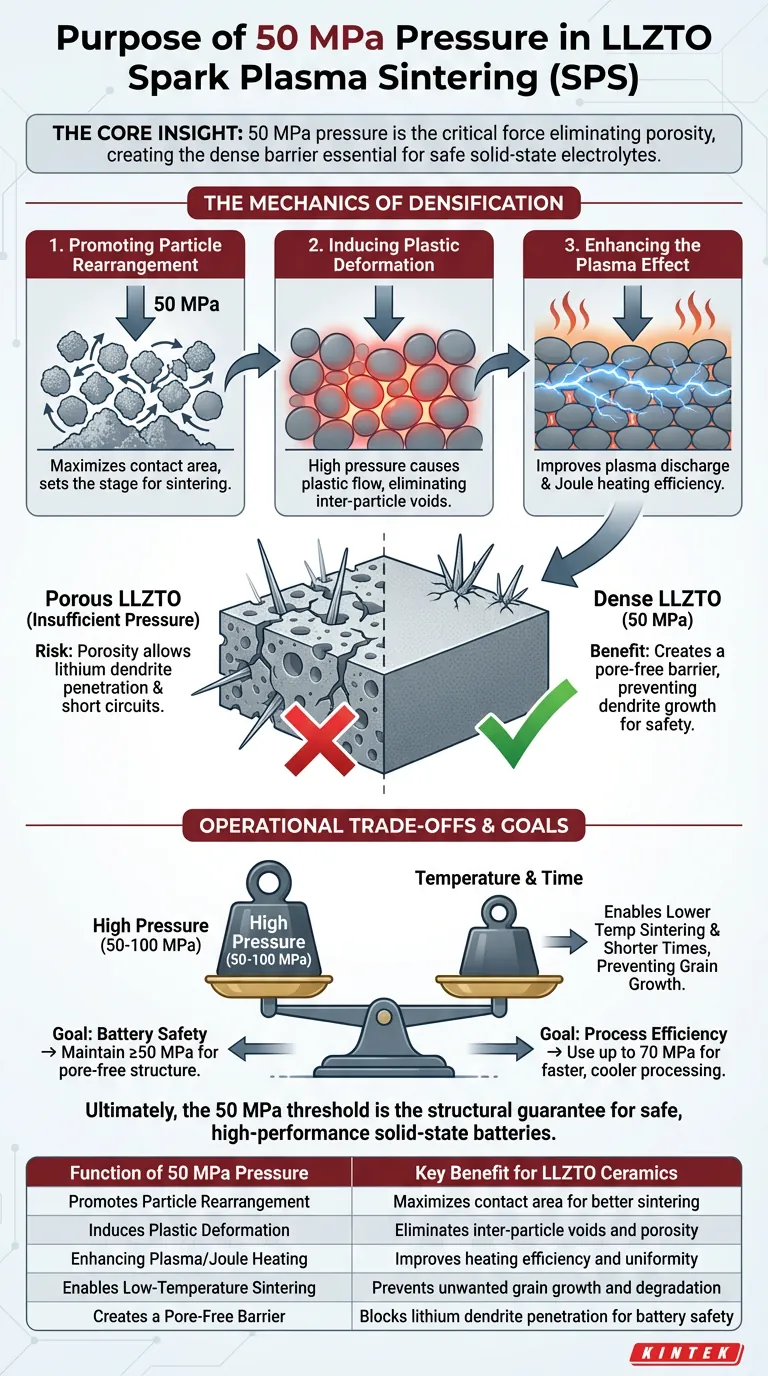

The Mechanics of Densification

Promoting Particle Rearrangement

Before the ceramic particles bond chemically, they must be packed as tightly as possible.

The application of 50 MPa forces the loose powder particles to shift and rotate, locking them into a tighter configuration. This initial rearrangement maximizes the contact area between particles, setting the stage for successful sintering.

Inducing Plastic Deformation

As the temperature rises, the ceramic particles soften.

Under the influence of high mechanical pressure, these particles undergo plastic flow, effectively squishing together to fill the interstitial spaces. This deformation is essential for eliminating the stubborn "inter-particle voids" that would otherwise remain as pores in the final product.

Enhancing the Plasma Effect

The pressure does more than just squeeze the material; it improves the electrical efficiency of the process.

Higher pressure promotes better contact between particles, which significantly enhances the plasma discharge and Joule heating effects generated by the pulsed current. This synergy ensures that heat is generated efficiently and uniformly throughout the sample.

Why Density Matters for LLZTO

Creating a Pore-Free Barrier

The primary goal of processing LLZTO is to create a solid electrolyte for batteries.

Any residual porosity in the ceramic acts as a pathway for failure. By maintaining 50 MPa, you effectively "close out" these pores, achieving a density that approaches the theoretical maximum for the material.

Preventing Lithium Dendrite Penetration

The most critical deep need for this process is safety and longevity.

A porous ceramic allows lithium dendrites (needle-like metal growths) to penetrate the electrolyte and cause short circuits. The high density achieved through this pressure creates a robust physical barrier that blocks dendrite growth, ensuring the battery remains safe and functional.

Understanding the Operational Trade-offs

Pressure vs. Temperature Balance

One of the distinct advantages of applying high pressure (50–100 MPa) is that it alters the thermal requirements of the process.

High pressure acts as a substitute for extreme heat. It allows you to achieve high-density nanoceramics at relatively low temperatures and in shorter timeframes. If you were to reduce the pressure, you would likely need to increase the temperature or sintering time, which could lead to unwanted grain growth or material degradation.

The Risk of Insufficient Pressure

Failing to maintain adequate pressure (e.g., dropping below the 50–70 MPa range) compromises the densification kinetics.

Without this mechanical driving force, the solid-state reactions may not complete efficiently. This leaves behind residual porosity, rendering the LLZTO pellet mechanically weak and susceptible to dendrite penetration.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To optimize your LLZTO sintering process, align your pressure parameters with your specific performance objectives:

- If your primary focus is Battery Safety: Maintain a minimum of 50 MPa to ensure a pore-free structure that effectively blocks lithium dendrite penetration.

- If your primary focus is Process Efficiency: Utilize high pressure (up to 70 MPa) to maximize Joule heating, allowing for shorter sintering times and lower processing temperatures.

Ultimately, the 50 MPa threshold is not just a processing parameter; it is the structural guarantee that your ceramic electrolyte will perform safely in a solid-state battery.

Summary Table:

| Function of 50 MPa Pressure | Key Benefit for LLZTO Ceramics |

|---|---|

| Promotes Particle Rearrangement | Maximizes contact area for better sintering |

| Induces Plastic Deformation | Eliminates inter-particle voids and porosity |

| Enhances Plasma/Joule Heating | Improves heating efficiency and uniformity |

| Enables Low-Temperature Sintering | Prevents unwanted grain growth and degradation |

| Creates a Pore-Free Barrier | Blocks lithium dendrite penetration for battery safety |

Need to optimize your LLZTO sintering process for maximum density and safety? KINTEK specializes in advanced lab press machines, including automatic and heated lab presses perfect for Spark Plasma Sintering applications. Our equipment provides the precise, high-pressure control (50-100 MPa) essential for producing dense, reliable solid-state electrolytes. Contact our experts today to discuss how our presses can enhance your battery research and development.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Machine

- Automatic Lab Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine

- Laboratory Hydraulic Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

- Electric Split Lab Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine

- Warm Isostatic Press for Solid State Battery Research Warm Isostatic Press

People Also Ask

- What feature of the hydraulic portable press helps monitor the pellet-making process? Discover the Key to Precise Sample Preparation

- What are the key steps for making good KBr pellets? Master Precision for Flawless FTIR Analysis

- How does a hydraulic press aid in XRF spectroscopy? Achieve Accurate Elemental Analysis with Reliable Sample Prep

- What are the limitations of hand-operated presses? Avoid Sample Compromise in Your Lab

- What are the advantages of using a hydraulic press for pellet production? Achieve Consistent, High-Quality Samples