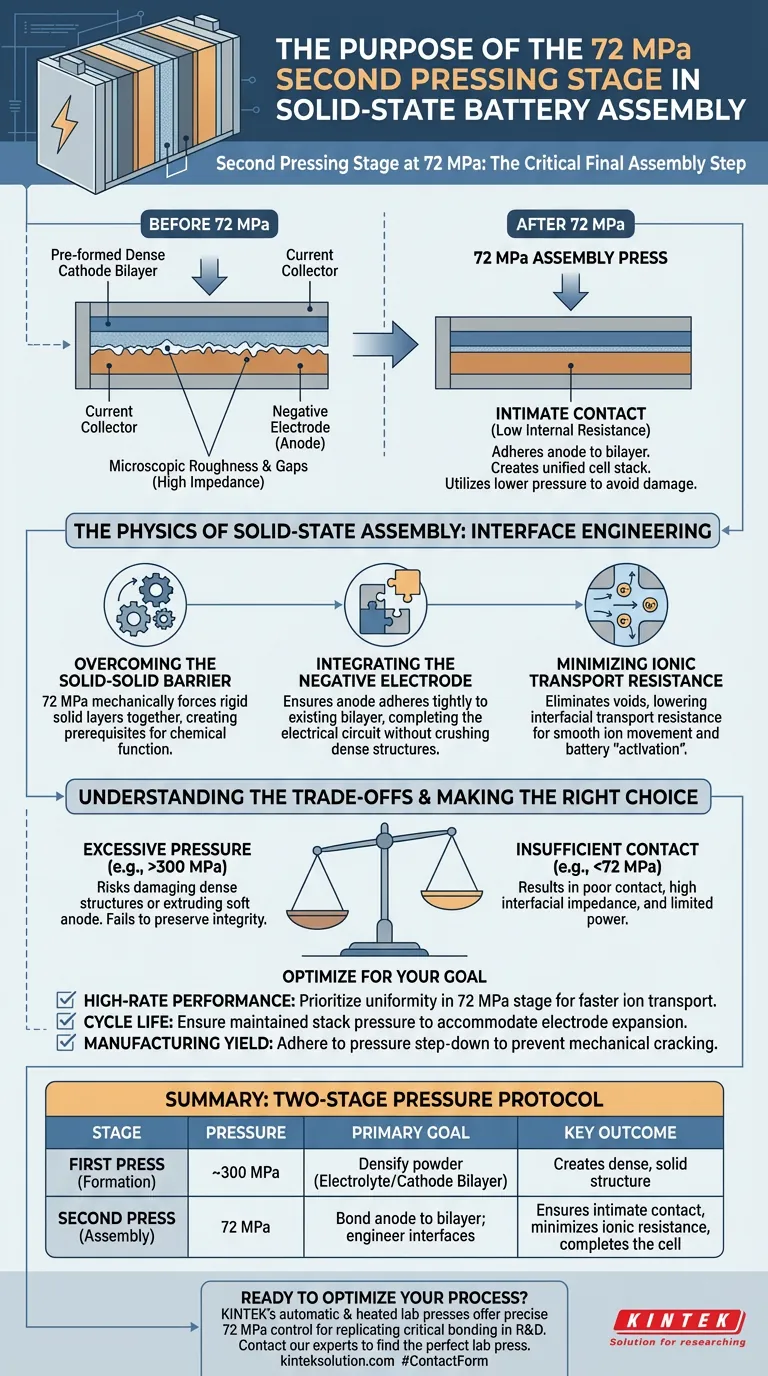

The second pressing stage at 72 MPa acts as the critical final assembly step for the solid-state battery cell. Its specific purpose is to adhere the negative electrode (anode) to the previously formed electrolyte/cathode bilayer and current collector. This creates a unified cell stack with uniform interfacial contact, utilizing a lower pressure than the initial formation stage to avoid damaging the dense structures already created.

While the primary high-pressure stage densifies the material powders, this secondary stage is focused on interface engineering. It eliminates microscopic voids between the solid layers to ensure low internal resistance, allowing the battery to function as a single, cohesive electrochemical unit.

The Physics of Solid-State Assembly

Overcoming the Solid-Solid Barrier

Unlike traditional batteries where liquid electrolyte flows into every crevice, solid-state batteries face a physical barrier. The interfaces between the cathode, solid electrolyte, and anode are rigid.

Without sufficient external force, these surfaces suffer from microscopic roughness and gaps. The 72 MPa pressing stage mechanically forces these solid layers together to create "intimate" physical contact, which is a prerequisite for chemical function.

Integrating the Negative Electrode

The assembly process is often sequential. Reference data indicates that the electrolyte and cathode are often pre-formed into a bilayer under significantly higher pressures (e.g., 300 MPa) to achieve maximum density.

The second stage introduces the negative electrode. Applying 72 MPa ensures this final component adheres tightly to the existing bilayer, completing the electrical circuit without crushing or deforming the dense ceramic or composite separator formed in step one.

Minimizing Ionic Transport Resistance

The ultimate goal of this pressure application is to reduce impedance. Any gap between layers acts as a roadblock for lithium or sodium ions moving through the cell.

By eliminating these voids, the secondary press lowers the interfacial transport resistance. This allows ions to move smoothly across the solid boundaries, which is essential for "activating" the battery and enabling high-rate performance.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Danger of Excessive Pressure

It is vital to distinguish between the two pressing stages. While the initial formation might utilize pressures up to 300 MPa to eliminate porosity in the powder, applying that same force during the final assembly is risky.

Excessive pressure at this stage can damage the dense structures formed earlier or extrude the softer anode material. The reduction to ~72 MPa is a calculated balance: high enough to bond the layers, but low enough to preserve structural integrity.

The Cost of Insufficient Contact

Conversely, failing to reach the pressure threshold results in "poor contact," a primary failure mode in solid-state systems. If the pressure drops too low, the interfacial impedance spikes.

This results in a battery with high internal resistance, severely limiting its ability to deliver power and reducing the overall efficiency of the electrochemical reaction.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The application of pressure is not just a manufacturing step; it is a variable that dictates the final characteristics of the cell.

- If your primary focus is High-Rate Performance: Prioritize uniformity in the 72 MPa stage to ensure minimized resistance, allowing for faster ion transport during rapid discharge.

- If your primary focus is Cycle Life: Ensure the assembly setup allows for maintained stack pressure (e.g., via clamped casings) to accommodate the volumetric expansion and contraction of electrodes over time.

- If your primary focus is Manufacturing Yield: strictly adhere to the pressure step-down protocol (high pressure for formation, lower pressure for assembly) to prevent mechanical cracking of the electrolyte layer.

Success in solid-state assembly relies on treating the secondary press not as a mere compaction step, but as the moment the components become a system.

Summary Table:

| Stage | Pressure | Primary Goal | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Press (Formation) | ~300 MPa | Densify powder materials (electrolyte/cathode bilayer) | Creates a dense, solid structure |

| Second Press (Assembly) | 72 MPa | Bond anode to bilayer; engineer interfaces | Ensures intimate contact, minimizes ionic resistance, completes the cell |

Ready to optimize your solid-state battery assembly process? The precise pressure control of KINTEK's automatic lab presses and heated lab presses is essential for replicating the critical 72 MPa bonding stage in your R&D. Our specialized equipment helps you achieve the uniform interfacial contact needed for high-performance, long-cycle-life batteries. Contact our experts today to find the perfect lab press for your research goals and ensure your components become a functional system.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Electric Lab Cold Isostatic Press CIP Machine

- Carbide Lab Press Mold for Laboratory Sample Preparation

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

People Also Ask

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in solid-state battery research? Enhance Pellet Performance

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in sulfide electrolyte pellets? Optimize Battery Densification

- What are the advantages of using a laboratory hydraulic press for catalyst samples? Improve XRD/FTIR Data Accuracy

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in FTIR characterization of silver nanoparticles?

- Why is a laboratory hydraulic press necessary for electrochemical test samples? Ensure Data Precision & Flatness