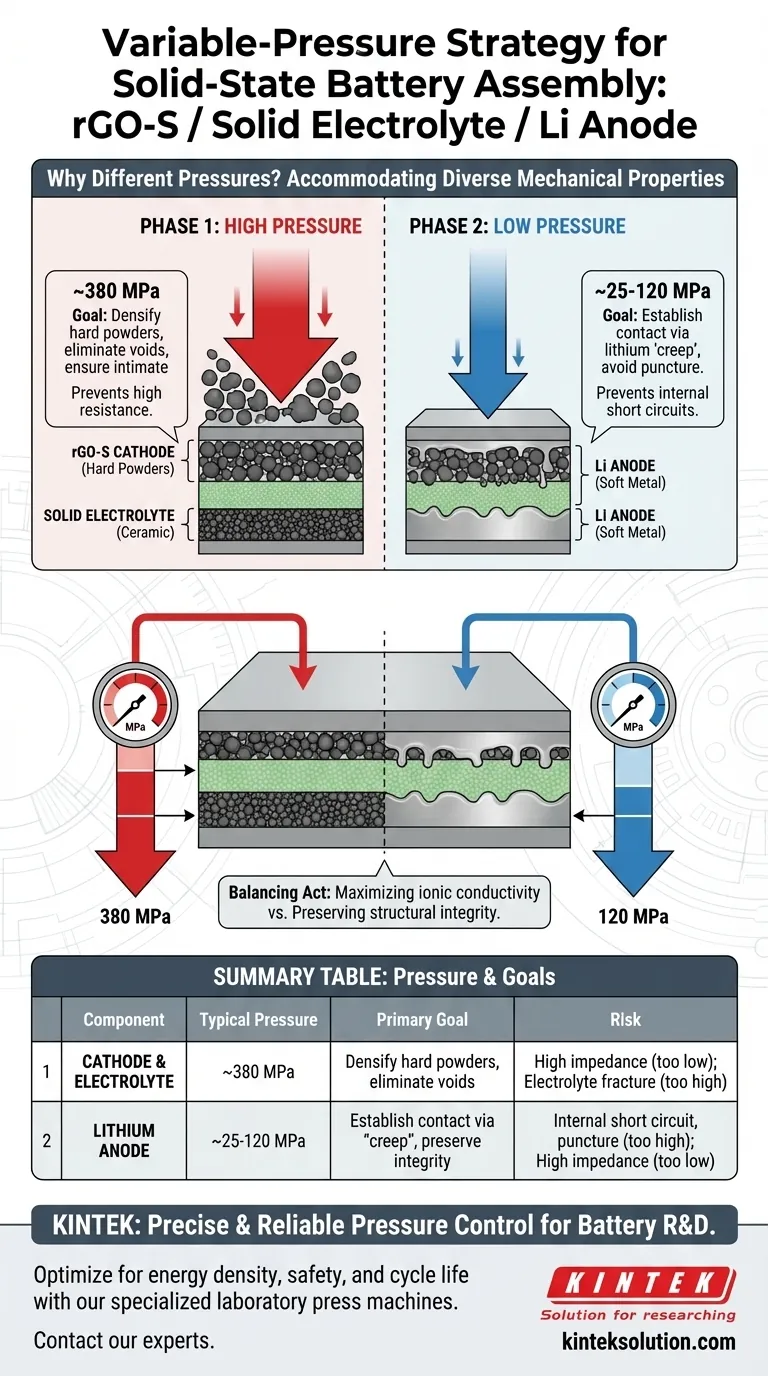

Different pressures are required to accommodate the vastly different mechanical properties of the battery components. High pressure (typically around 380 MPa) is necessary to densify the hard cathode and solid electrolyte powders into a cohesive layer. In contrast, a significantly lower pressure (around 120 MPa) is applied to the lithium anode to avoid deforming the soft metal or puncturing the electrolyte layer.

The assembly of solid-state batteries is a balancing act between maximizing ionic conductivity and preserving structural integrity. A variable-pressure strategy ensures intimate solid-solid contact at the rigid cathode interface while preventing short circuits at the delicate lithium anode interface.

The Challenge of Solid-Solid Interfaces

The "Contact Problem"

Unlike liquid electrolytes that naturally flow into pores, solid-state batteries rely on solid-to-solid contact.

Reducing Interfacial Resistance

If particles merely touch loosely, the contact area is small, leading to high resistance. Pressure forces particles together, increasing the active area for lithium ions to pass through.

Phase 1: High Pressure for Cathode and Electrolyte

The first stage of assembly often involves the Reduced Graphene Oxide-Sulfur (rGO-S) cathode and the solid electrolyte.

Densifying Hard Powders

The electrolyte and cathode materials are typically ceramic or composite powders. They are hard and rigid.

Eliminating Voids

To create a conductive pathway, you must apply immense pressure (e.g., 380–400 MPa). This crushes the powder into a dense, pore-free pellet, eliminating air voids that would otherwise block ion transport.

Ensuring Mechanical Bonding

High pressure creates a robust mechanical bond between the cathode and the electrolyte. This intimate interface is critical for rate performance and cycle life.

Phase 2: Lower Pressure for the Lithium Anode

Once the lithium metal anode is introduced, the pressure strategy must change drastically.

The Plasticity of Lithium

Lithium metal is extremely soft and malleable. It behaves plastically, meaning it deforms permanently under stress.

The "Creep" Effect

Because lithium is soft, it naturally "creeps" or flows into microscopic surface irregularities. Therefore, it requires much lower pressure (e.g., 25–120 MPa) to establish good contact compared to hard ceramic powders.

Preventing Catastrophic Failure

If you applied the same high pressure (380 MPa) to the lithium, you would squeeze the metal too aggressively. This could cause the lithium to puncture the solid electrolyte layer, leading to an immediate internal short circuit.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Risk of Over-Pressurization

Applying excessive pressure to the entire cell stack risks fracturing the solid electrolyte particles or the membrane itself. A cracked electrolyte allows lithium dendrites to penetrate, compromising safety.

The Risk of Under-Pressurization

Insufficient pressure at the cathode side leaves voids. This results in high impedance (resistance), which severely limits the battery's power output and efficiency.

Balancing Material Limits

The variable pressure approach acknowledges that the optimal pressure for densification is often higher than the structural limit of the anode material.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

When designing your assembly protocol, consider which interface dictates your pressure limits.

- If your primary focus is maximizing energy density: Prioritize high pressure on the cathode/electrolyte composite first to achieve the highest possible pellet density and minimize volume.

- If your primary focus is safety and cycle life: Strictly limit the pressure applied after the lithium anode is added to prevent micro-punctures that could degrade the cell over time.

Success in solid-state battery assembly relies on treating the cathode as a ceramic to be compacted and the anode as a soft metal to be sealed.

Summary Table:

| Component | Typical Pressure | Primary Goal | Risk of Incorrect Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathode & Electrolyte | ~380 MPa | Densify hard powders, eliminate voids, ensure ionic contact | High resistance, poor performance (if too low); Electrolyte fracture (if too high) |

| Lithium Anode | ~25-120 MPa | Establish contact via lithium 'creep', preserve structural integrity | Internal short circuit, punctured electrolyte (if too high); High impedance (if too low) |

Achieve precise and reliable pressure control for your battery R&D. The success of your solid-state battery prototypes hinges on the precise application of pressure during assembly. KINTEK specializes in laboratory press machines, including automatic and heated lab presses, designed to deliver the controlled, variable pressures required for densifying cathode materials like rGO-S while safely handling delicate lithium anodes.

Our expertise ensures you can optimize for energy density, safety, and cycle life. Let us help you build a better battery. Contact our experts today to discuss your specific lab press requirements.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press for XRF KBR FTIR Lab Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Lab Hydraulic Press

People Also Ask

- What is the role of a hydraulic press in KBr pellet preparation for FTIR? Achieve High-Resolution Chemical Insights

- What role does a high-pressure laboratory hydraulic press play in KBr pellet preparation? Optimize FTIR Accuracy

- What role does a laboratory hydraulic press play in carbonate powder prep? Optimize Your Sample Analysis

- What are some laboratory applications of hydraulic presses? Boost Precision in Sample Prep and Testing

- Why must a laboratory hydraulic press be used for pelletizing samples for FTIR? Achieve Precision in Spectral Data