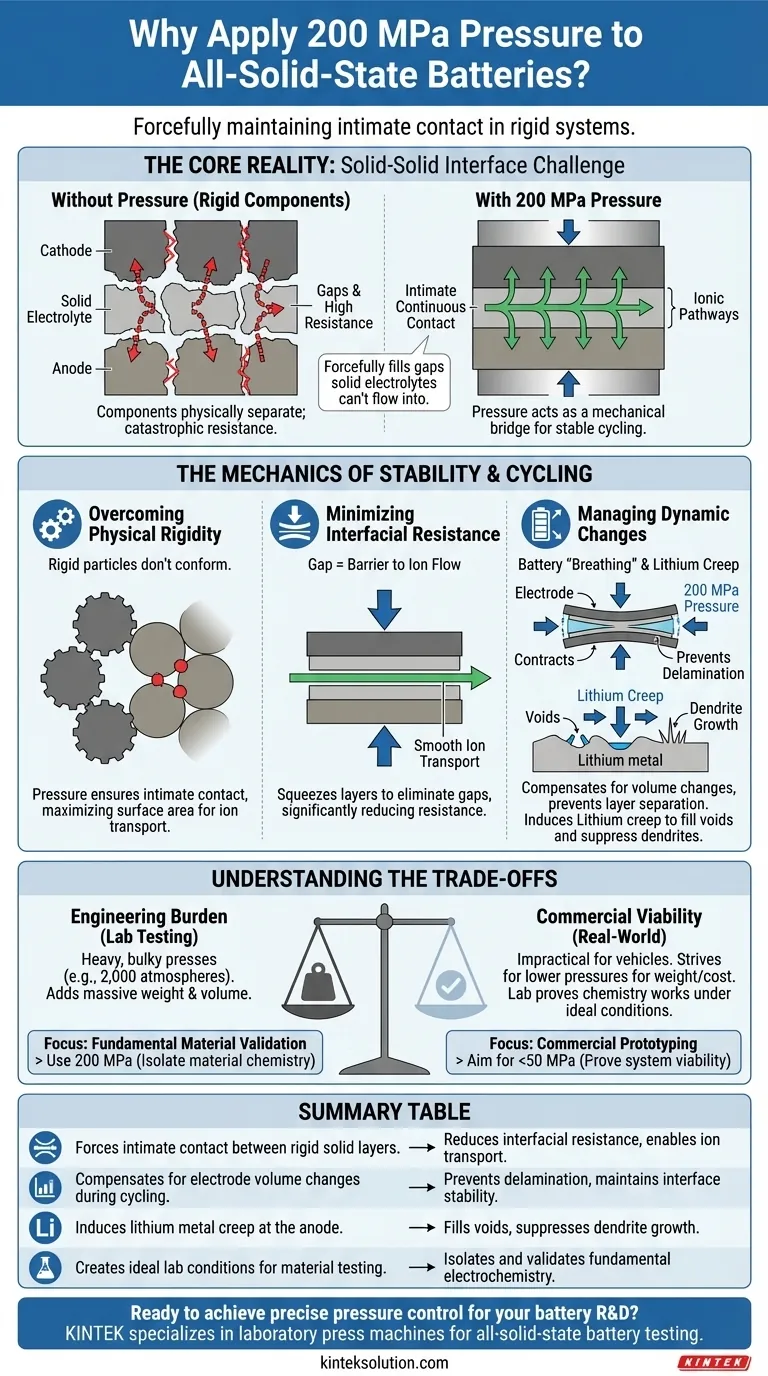

A continuous external pressure of 200 MPa is applied to forcefully maintain intimate contact between the internal solid layers of the battery. Because solid-state electrolytes and electrodes are rigid, they do not naturally flow to fill gaps like liquid electrolytes do. This high pressure compensates for volume changes and stress relaxation, ensuring that ionic pathways remain open and unobstructed for stable, long-term cycling.

The Core Reality: The fundamental challenge in solid-state batteries is the "solid-solid interface." Without significant external pressure to act as a mechanical bridge, the rigid components will physically separate during operation, causing a catastrophic rise in resistance and battery failure.

The Mechanics of Interface Stability

Overcoming Physical Rigidity

In traditional batteries, liquid electrolytes wet the electrode surfaces, filling every microscopic pore. Solid-state batteries lack this inherent conformability.

The cathode, anode, and solid electrolyte are distinct, rigid particles. Without external force, these particles merely touch at rough points rather than forming a continuous connection.

Pressure ensures these rigid particles establish intimate, continuous physical contact. This is required to maximize the surface area available for lithium ions to transport across the interface.

Minimizing Interfacial Resistance

The primary enemy of battery performance is resistance. Any gap between the solid layers acts as a barrier to ion flow.

By applying 200 MPa, you effectively squeeze the layers together to eliminate these gaps. This creates a tight junction that allows for smooth transport of lithium ions, significantly reducing interfacial resistance and improving the battery's critical current density.

Managing Dynamic Changes During Cycling

Compensating for Volume Expansion ("Breathing")

Batteries are not static; they "breathe" during operation. As lithium ions move in and out of the electrode materials, the materials expand and contract.

In a solid-state system, this volume change can lead to delamination, where the layers pull apart. Constant external pressure acts as a counter-force, keeping the layers pressed together even as they change size, preventing interface separation.

Utilizing Lithium Creep

Pressure plays a unique role when lithium metal is used as the anode. Lithium is a relatively soft metal that exhibits "creep" behavior—it can flow like a very viscous fluid under stress.

High pressure induces this creep, forcing the lithium to actively fill interfacial voids created during the stripping (discharge) process. This prevents the formation of voids and suppresses the growth of lithium dendrites, which are needle-like structures that can short-circuit the battery.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While 200 MPa is effective for achieving high performance in a laboratory setting, it presents significant engineering challenges.

The Engineering Burden

Applying 200 MPa (approximately 2,000 atmospheres) requires heavy, bulky hydraulic presses or clamping rigs. This adds massive weight and volume to the battery system.

Commercial Viability

For commercial applications like electric vehicles, maintaining such high pressure is often impractical. While 200 MPa ensures great test results (e.g., 400+ stable cycles), real-world pack designs often strive for much lower pressures to reduce weight and cost.

Therefore, 200 MPa is often used in testing to prove the material chemistry works under ideal conditions, even if the final commercial packaging must find a way to operate at lower pressures.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The application of pressure is a variable that dictates how you interpret battery data.

- If your primary focus is Fundamental Material Validation: Use high pressure (like 200 MPa) to eliminate mechanical contact issues so you can study the true electrochemical limits of the material chemistry itself.

- If your primary focus is Commercial Prototyping: You must aim to achieve similar stability at significantly lower pressures (e.g., <50 MPa) to prove the system is viable for practical, lightweight applications.

Ultimately, the application of pressure is the mechanical substitute for the fluidity of liquid electrolytes, bridging the gap between rigid components to enable energy storage.

Summary Table:

| Function of 200 MPa Pressure | Benefit for Solid-State Battery |

|---|---|

| Forces intimate contact between rigid solid layers | Reduces interfacial resistance, enables ion transport |

| Compensates for electrode volume changes during cycling | Prevents delamination, maintains interface stability |

| Induces lithium metal creep at the anode | Fills voids, suppresses dendrite growth |

| Creates ideal lab conditions for material testing | Isolates and validates fundamental electrochemistry |

Ready to achieve precise pressure control for your battery R&D? KINTEK specializes in laboratory press machines, including automatic and heated lab presses, designed to meet the demanding requirements of all-solid-state battery testing. Our equipment helps you validate material performance with accuracy and reliability. Contact our experts today to discuss how our solutions can support your energy storage innovations!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press for XRF KBR FTIR Lab Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

People Also Ask

- Why is it necessary to use a laboratory hydraulic press for pelletizing? Optimize Conductivity of Composite Cathodes

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in solid-state battery research? Enhance Pellet Performance

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in FTIR characterization of silver nanoparticles?

- Why is a laboratory hydraulic press necessary for electrochemical test samples? Ensure Data Precision & Flatness

- What is the significance of uniaxial pressure control for bismuth-based solid electrolyte pellets? Boost Lab Accuracy