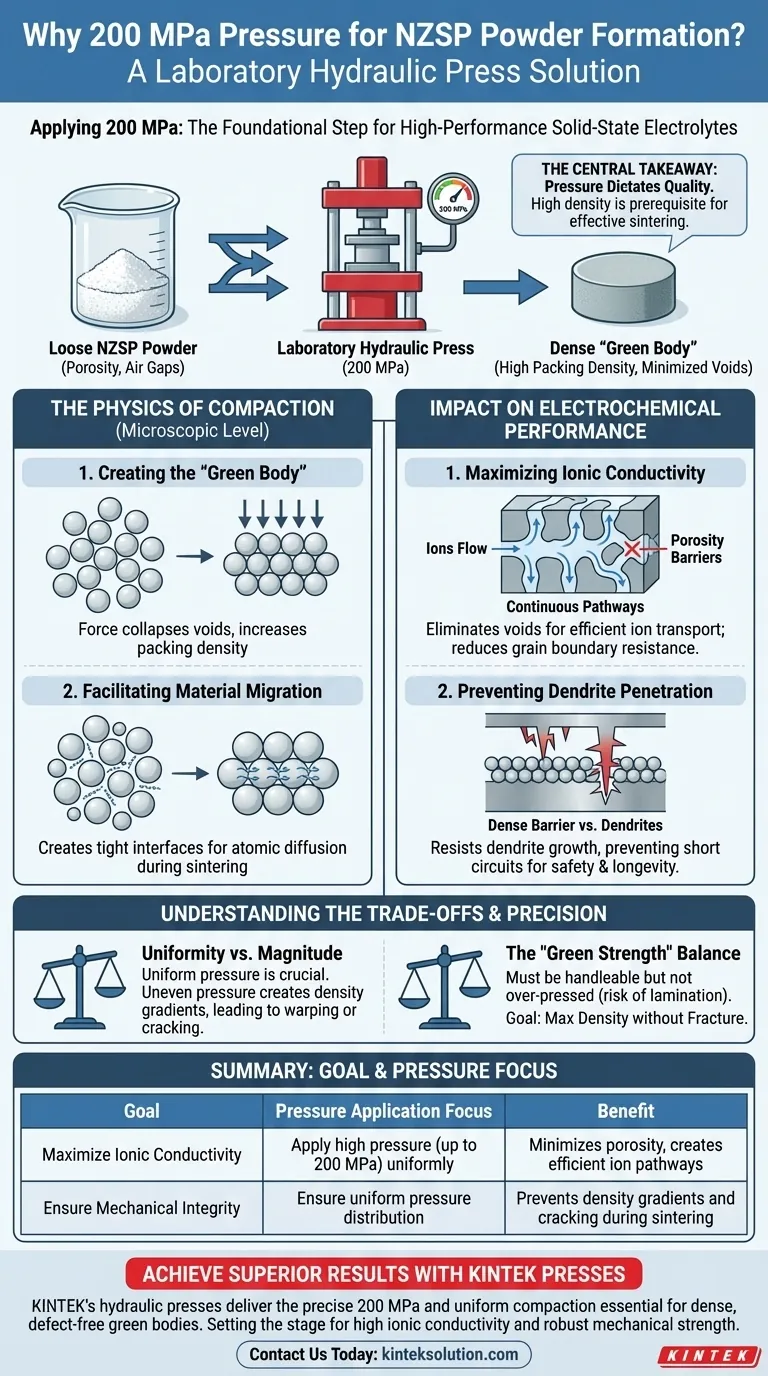

Applying 200 MPa of pressure is the foundational step for creating a high-performance solid-state electrolyte. This process uses a laboratory hydraulic press to transform loose Na₃Zr₂Si₂PO₁₂ (NZSP) powder into a dense, cohesive "green body." By mechanically forcing the powder particles together, this pressure eliminates the majority of air voids and maximizes the contact area between particles, setting the stage for the chemical bonding that occurs later.

The Central Takeaway: The pressure applied during compaction dictates the ultimate quality of the ceramic. A high-density green body is the absolute prerequisite for effective sintering; without it, the final electrolyte will suffer from high porosity, poor conductivity, and structural weakness.

The Physics of Compaction

To understand why 200 MPa is necessary, you must look at what happens to the powder at a microscopic level.

Creating the "Green Body"

The immediate goal of the hydraulic press is to form a "green body"—a pellet that is compressed but not yet fired.

Loose powder creates a structure full of macroscopic defects and air gaps. Applying 200 MPa forcibly collapses these voids, increasing the packing density of the material.

Facilitating Material Migration

High pressure does more than just shape the powder; it creates tight physical interfaces between grains.

During the subsequent high-temperature sintering phase, atoms need to migrate across particle boundaries to fuse the material.

If the particles are not physically touching due to low pressure, this migration cannot occur efficiently. The initial mechanical compaction drives the particles close enough to promote effective densification during heat treatment.

Impact on Electrochemical Performance

The physical density achieved by the press directly correlates to the electrical capabilities of the final NZSP ceramic.

Maximizing Ionic Conductivity

For an electrolyte to function, ions must travel through the material with minimal resistance.

Porosity acts as a barrier to this movement. By eliminating voids via high-pressure pressing, you create continuous, orderly pathways for ion transport.

This reduction in grain boundary resistance is essential for achieving high ionic conductivity in the final cell.

Preventing Dendrite Penetration

Mechanical strength is a critical safety feature in solid-state batteries.

If the ceramic pellet retains porosity or macroscopic defects, sodium dendrites (metal filaments) can grow through the voids.

A highly dense, non-porous structure formed at 200 MPa creates a physical barrier that resists this penetration, preventing short circuits and ensuring the battery's longevity.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While applying high pressure is necessary, it requires precision to avoid introducing new defects.

Uniformity vs. Magnitude

Applying 200 MPa is effective only if the pressure is distributed uniformly across the die.

If the pressure is uneven, density gradients will form within the pellet. This often leads to differential shrinkage during sintering.

The result is a ceramic that may warp, crack, or deform when heated, rendering the electrolyte useless regardless of its theoretical density.

The "Green Strength" Balance

The green body must have sufficient mechanical strength to be handled before sintering.

However, over-pressing or improper pressure release can sometimes cause lamination (layer separation) within the pellet.

The goal is to achieve maximum density without exceeding the mechanical limits of the powder's ability to cohere without fracturing.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The pressure you apply is a variable that tunes the physical properties of your electrolyte.

- If your primary focus is Ionic Conductivity: Prioritize maximizing pressure (up to the 200 MPa standard) to minimize porosity and reduce grain boundary resistance.

- If your primary focus is Mechanical Integrity: Focus on the uniformity of the pressure application to prevent density gradients that lead to cracking during sintering.

High-pressure compaction is not merely a shaping step; it is the primary method for minimizing internal resistance and maximizing the lifespan of the battery.

Summary Table:

| Goal | Pressure Application Focus | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Maximize Ionic Conductivity | Apply high pressure (up to 200 MPa) uniformly | Minimizes porosity, creates efficient ion pathways |

| Ensure Mechanical Integrity | Ensure uniform pressure distribution | Prevents density gradients and cracking during sintering |

Ready to achieve superior density and performance in your solid-state electrolyte research?

The precise 200 MPa pressure required for forming NZSP powder is exactly what KINTEK's laboratory hydraulic presses are designed to deliver. Our automatic lab presses, isostatic presses, and heated lab presses provide the uniform, high-pressure compaction essential for creating dense, defect-free green bodies, setting the stage for high ionic conductivity and robust mechanical strength in your final product.

Contact us today to discuss how our specialized lab press machines can enhance your battery material development. Let's build the future of energy storage, together.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Machine for Glove Box

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Lab Hydraulic Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

People Also Ask

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in FTIR characterization of silver nanoparticles?

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in solid-state battery research? Enhance Pellet Performance

- What is the significance of uniaxial pressure control for bismuth-based solid electrolyte pellets? Boost Lab Accuracy

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in LLZTO@LPO pellet preparation? Achieve High Ionic Conductivity

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in sulfide electrolyte pellets? Optimize Battery Densification