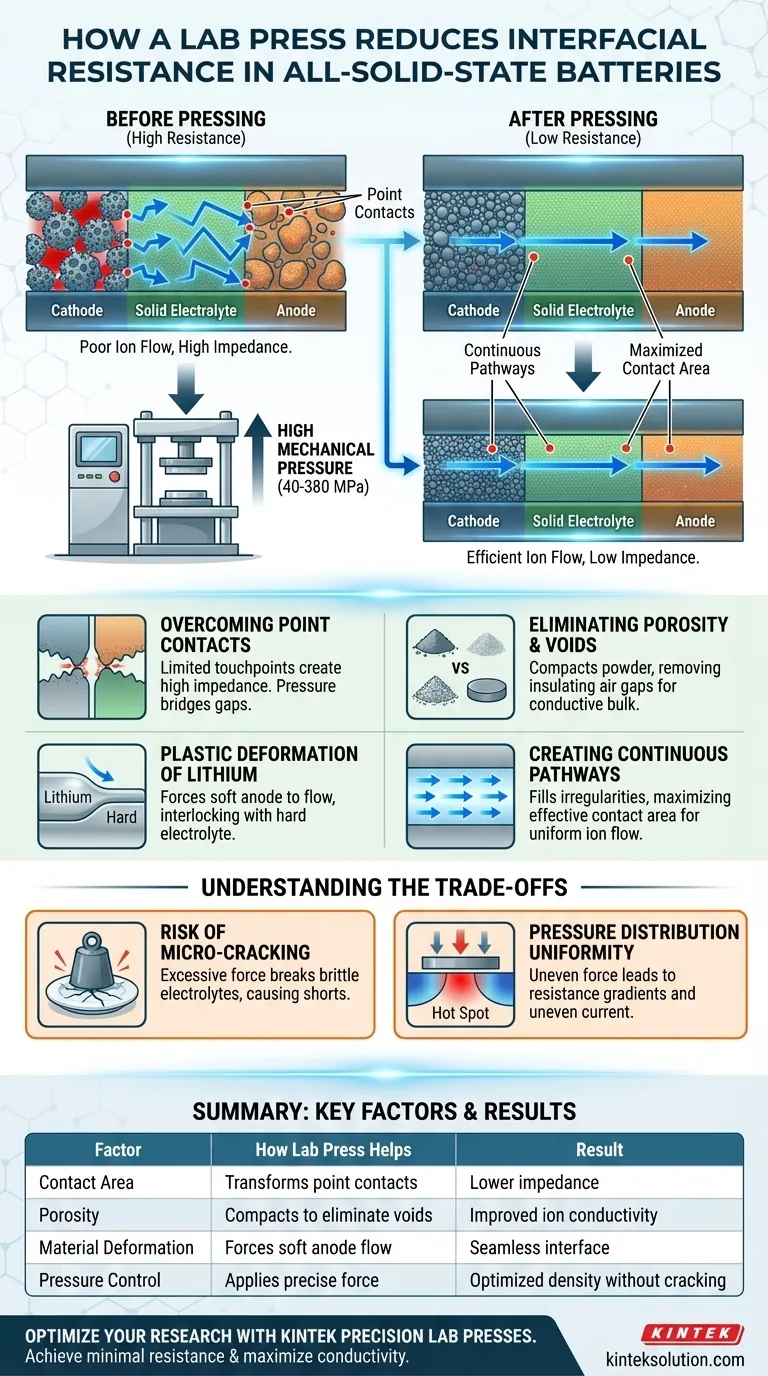

A lab press machine significantly reduces interfacial resistance by applying high mechanical pressure to compact solid battery components—such as cathodes, anodes, and electrolytes—into a dense, unified structure. This physical compression eliminates microscopic voids and maximizes the contact area between solid particles, transforming ineffective "point contacts" into continuous pathways that allow lithium ions to travel efficiently.

In all-solid-state batteries, the primary barrier to performance is the lack of physical connection between rigid solid layers. The lab press solves this by mechanically forcing materials into intimate contact, bridging the gaps that otherwise block ion flow.

The Mechanics of Reducing Resistance

Overcoming the "Point Contact" Limitation

Unlike liquid electrolytes that naturally wet electrode surfaces, solid-state materials are rigid. When simply placed together, they only touch at specific microscopic points.

This limited contact area creates extremely high impedance. A lab press applies significant force (often between 40 to 380 MPa) to overcome this natural rigidity.

Eliminating Porosity and Voids

Powdered materials, such as solid electrolytes and cathode composites, naturally contain air gaps and pores. These voids act as insulators, stopping ions in their tracks.

By cold-pressing these powders into pellets, the machine drastically increases the density of the material. This compaction removes internal porosity, ensuring that the bulk material is conductive rather than resistive.

Material-Specific Interactions

Plastic Deformation of Lithium Anodes

The benefits of the lab press are particularly evident when working with lithium metal anodes and rigid electrolytes, such as garnets.

Because lithium is relatively soft, the pressure from the machine forces it to undergo plastic deformation. The metal literally flows into the microscopic depressions and roughness of the harder electrolyte surface.

Creating Continuous Ion Pathways

This deformation creates a seamless interface where the two materials interlock.

By filling surface irregularities, the press maximizes the effective contact area. This ensures that ions can pass uniformly across the interface, rather than being funneled through narrow contact points.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Risk of Micro-Cracking

While high pressure is essential for reducing resistance, excessive force can be detrimental. Applying too much pressure, particularly to brittle ceramic electrolytes, can induce micro-cracks.

These cracks can eventually lead to short circuits or structural failure within the battery.

Pressure Distribution Uniformity

A uniaxial hydraulic press applies force from one direction. If the powder is not distributed evenly, or if the die is imperfect, density gradients can occur.

This results in "hot spots" of low resistance and other areas of high resistance, leading to uneven current distribution during battery operation.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Achieving the lowest possible interfacial resistance requires balancing pressure magnitude with material integrity.

- If your primary focus is Electrolyte Densification: Apply higher pressures (up to 380 MPa) to create a pore-free, dense pellet before introducing electrode layers.

- If your primary focus is Full Cell Assembly: Use controlled, moderate pressure to press the cathode and anode against the electrolyte to ensure adhesion without fracturing the separator.

The lab press is not just a shaping tool; it is the fundamental enabler of ionic conductivity in solid-state architecture.

Summary Table:

| Factor | How Lab Press Helps | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Contact Area | Transforms point contacts into continuous pathways | Lower impedance |

| Porosity | Compacts powders to eliminate insulating voids | Improved ion conductivity |

| Material Deformation | Forces soft anodes to fill surface irregularities | Seamless interface |

| Pressure Control | Applies precise force (40-380 MPa) | Optimized density without cracking |

Ready to optimize your all-solid-state battery research? KINTEK's precision lab press machines (including automatic, isostatic, and heated models) are engineered to deliver the uniform pressure and control you need to achieve minimal interfacial resistance and maximize ionic conductivity. Let our expertise support your laboratory's innovation—contact us today to discuss your specific application!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

- Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press for XRF KBR FTIR Lab Press

People Also Ask

- Why is a precise pressure of 98 MPa applied by a laboratory hydraulic press? To Ensure Optimal Densification for Solid-State Battery Materials

- How do you operate a manual hydraulic pellet press? Master Precise Sample Preparation for Accurate Analysis

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in solid-state battery electrolyte preparation? Achieve Superior Densification and Performance

- What safety features are included in manual hydraulic pellet presses? Essential Mechanisms for Operator and Equipment Protection

- What are the key features of manual hydraulic pellet presses? Discover Versatile Lab Solutions for Sample Prep