A multi-step pressing process is the fundamental requirement for overcoming the physical limitations of solid-solid interfaces in all-solid-state sodium-ion batteries. By applying varying pressures using a lab press, you decouple the densification of the electrolyte from the bonding of the electrodes. This ensures that the electrolyte layer achieves high internal density—critical for blocking dendrites—while subsequently creating an intimate, low-resistance connection with the cathode and anode that a single pressing step cannot reliably achieve.

Core Insight

In the absence of a liquid electrolyte to "wet" surfaces and fill gaps, mechanical force is the only variable that allows ions to move between layers. A multi-step process allows you to optimize the internal density of individual components first, and then optimize the interfacial contact between them, minimizing the impedance that typically kills solid-state battery performance.

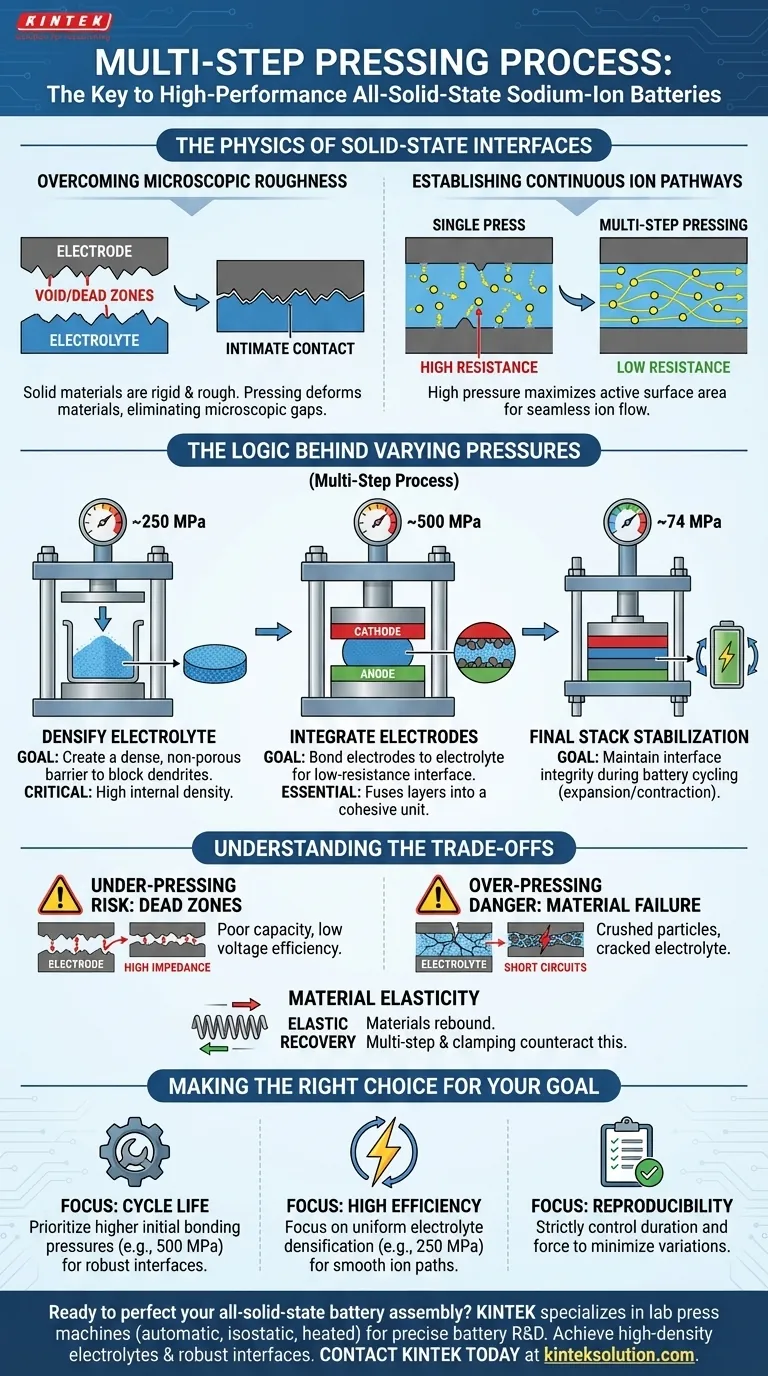

The Physics of Solid-State Interfaces

Overcoming Microscopic Roughness

Unlike liquid electrolytes, solid materials have rigid, rough surfaces on a microscopic level. When two solid layers are simply placed together, they only touch at the highest peaks of their surface topography.

These gaps create voids where ions cannot travel, leading to massive interfacial resistance. Pressing is required to plastically deform these materials, forcing them to interlock and eliminating microscopic gaps.

Establishing Continuous Ion Pathways

The primary goal of assembly is to create a seamless "highway" for sodium ions. If the layers are not pressed firmly enough, the contact points are sparse, restricting the flow of ions.

By applying high pressure, you maximize the active surface area where the cathode, electrolyte, and anode meet. This direct physical contact is the prerequisite for reducing interfacial impedance and enabling high-rate electrochemical performance.

The Logic Behind Varying Pressures

Step 1: Densifying the Electrolyte

The first stage of pressing typically targets the solid electrolyte layer alone. For example, applying a pressure of approximately 250 MPa ensures the electrolyte powder is compacted into a dense, non-porous pellet.

High density in this layer is non-negotiable. It creates the structural integrity required to handle the cell and acts as a physical barrier to prevent short circuits between the anode and cathode.

Step 2: Integrating the Electrodes

Once the electrolyte is densified, the electrode materials (such as the cathode) are added. A second, often higher pressure (e.g., 500 MPa) is applied to bond this new layer to the existing electrolyte pellet.

This varying pressure strategy is essential because it fuses the distinct layers into a single, cohesive unit. It ensures the electrode particles embed slightly into the electrolyte surface, creating a robust interface that can withstand the volume changes inherent in battery cycling.

Step 3: Final Stack Stabilization

After the initial fabrication, a lower, constant stacking pressure (e.g., around 74 MPa) is often maintained. This ensures that the interfaces remain void-free even as the materials expand and contract during operation.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Risk of Under-Pressing

If the pressure is too low during any stage, "dead zones" will remain at the interface. These voids drive up internal resistance, causing the battery to suffer from poor capacity and low voltage efficiency.

The Danger of Over-Pressing

While high pressure is necessary, excessive force can be destructive. It can crush the active material particles or cause the electrolyte pellet to crack, leading to immediate cell failure or short circuits.

Material Elasticity

Solid materials often exhibit "elastic recovery," meaning they try to bounce back to their original shape after the press is released. A multi-step process helps mitigate this by progressively stabilizing the structure, but external clamping pressure is often still required during testing to counteract this rebound.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To optimize your sodium-ion battery assembly, align your pressing protocol with your specific performance targets:

- If your primary focus is Cycle Life: Prioritize higher initial bonding pressures (e.g., 500 MPa) to ensure the interface is robust enough to survive repeated expansion and contraction.

- If your primary focus is High Efficiency: Focus on the uniformity of the electrolyte densification step (e.g., 250 MPa) to ensure the smoothest possible ion path with zero porosity.

- If your primary focus is Reproducibility: strictly control the duration of the pressure application, not just the force, to minimize variations in elastic recovery between batches.

Achieving the optimal all-solid-state battery is not just about chemistry; it is about the precise mechanical engineering of the interface.

Summary Table:

| Pressing Step | Typical Pressure | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Densify Electrolyte | ~250 MPa | Create a dense, non-porous electrolyte layer to block dendrites. |

| Step 2: Integrate Electrodes | ~500 MPa | Bond electrodes to the electrolyte, creating an intimate, low-resistance interface. |

| Step 3: Final Stack Stabilization | ~74 MPa | Maintain interface integrity during battery cycling to counteract material expansion/contraction. |

Ready to perfect your all-solid-state battery assembly? KINTEK specializes in lab press machines (automatic lab press, isostatic press, heated lab press, etc.), serving the precise needs of battery research and development laboratories. Our equipment delivers the controlled, multi-step pressing processes essential for achieving high-density electrolytes and robust electrode interfaces. Let us help you enhance your battery's cycle life, efficiency, and reproducibility. Contact KINTEK today to discuss your specific requirements!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Machine for Glove Box

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

People Also Ask

- Why is the hydraulic portable press considered accessible for everyone in the lab? Unlock Effortless Force and Precision for All Users

- How are hydraulic presses used in spectroscopy and compositional determination? Enhance Accuracy in FTIR and XRF Analysis

- How are hydraulic pellet presses used in educational and industrial settings? Boost Efficiency in Labs and Workshops

- What are the advantages of using a hydraulic mini press? Achieve Precise Force in a Compact Lab Tool

- How do hydraulic pellet presses contribute to material testing and research? Unlock Precision in Sample Prep and Simulation