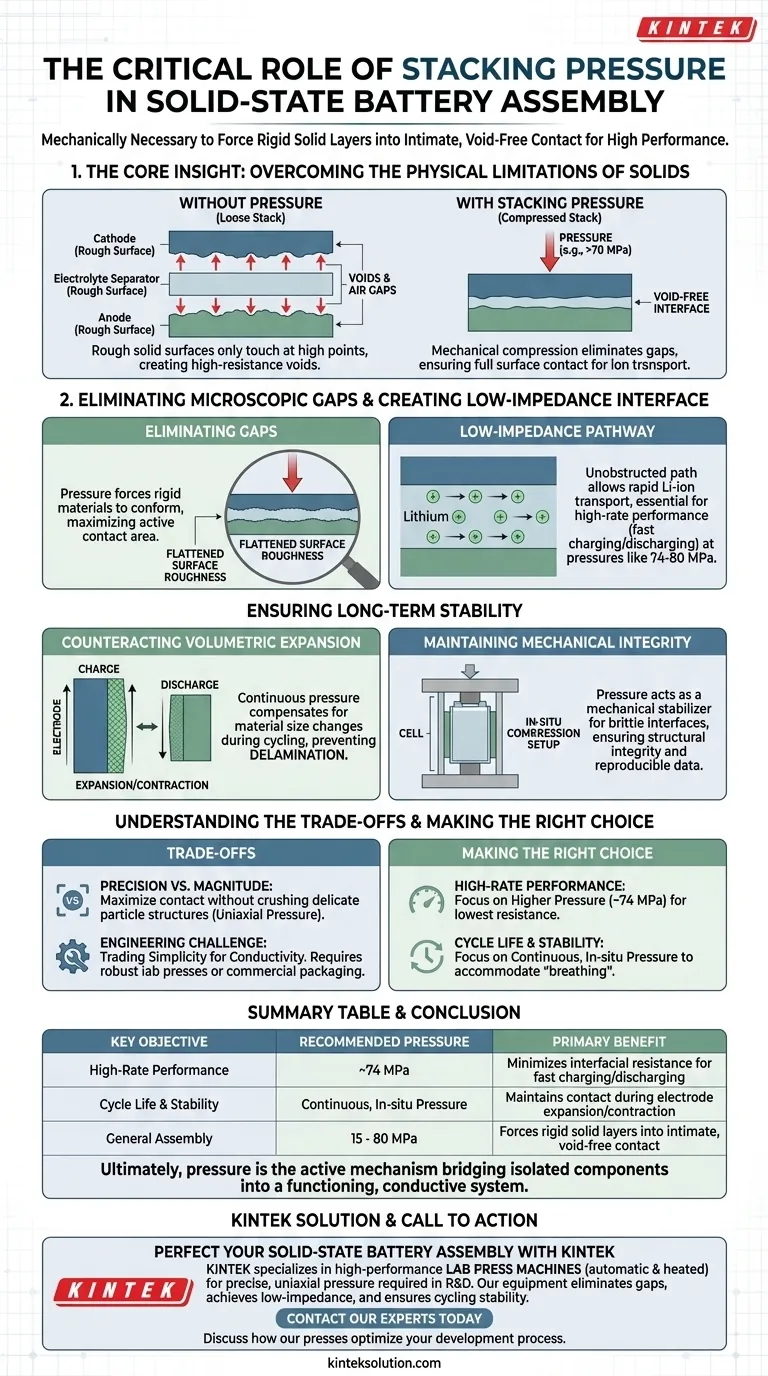

Applying specific stacking pressure during final assembly is mechanically necessary to force rigid solid layers—the cathode, anode, and electrolyte—into intimate, void-free contact. Because solid materials cannot flow to fill microscopic gaps like liquid electrolytes, significant pressure (often exceeding 70 MPa) is required to flatten surface roughness and create the continuous physical connection required for ion transport.

The Core Insight The fundamental challenge in solid-state batteries is the "solid-solid interface." Unlike liquid batteries where contact is automatic, solid-state cells require external force to overcome microscopic surface irregularities; without this pressure, the battery suffers from high resistance and may fail to activate entirely.

Overcoming the Physical Limitations of Solids

Eliminating Microscopic Gaps

On a microscopic level, the surfaces of solid cathodes, anodes, and electrolyte separators are rough and uneven. Without external force, these layers only touch at specific high points, leaving "voids" or air gaps between them.

Stacking pressure mechanically compresses these layers together. This eliminates the voids and ensures the entire surface area of the electrode is in active contact with the electrolyte.

Creating a Low-Impedance Interface

The primary obstacle to solid-state performance is interfacial resistance. If the layers are not pressed tightly together, the resistance to ionic flow is too high.

By applying pressures around 74-80 MPa, you create a "low-impedance" interface. This unobstructed pathway allows lithium ions to transport rapidly between components, which is a prerequisite for high-rate performance (fast charging and discharging).

Ensuring Long-Term Stability

Counteracting Volumetric Expansion

Battery materials physically change size during operation. As lithium ions move during charge and discharge cycles, the electrode materials expand and contract.

A stable, controlled pressure is required not just to create the interface, but to maintain it. This pressure compensates for these volumetric changes, preventing the layers from physically separating (delaminating) over time.

Maintaining Mechanical Integrity

Solid-state cells rely on rigid solid-solid interfaces. These interfaces are brittle and prone to fracture or separation under stress.

Applying continuous pressure, often via a cell holder or in-situ compression setup during testing, acts as a mechanical stabilizer. It ensures the cell retains its structural integrity through repeated cycling, yielding reproducible and authentic performance data.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Precision vs. Magnitude

While high pressure is necessary, it must be applied with precision (e.g., uniaxial pressure). The goal is to maximize contact area without crushing the delicate particle structures within the active materials.

The Engineering Challenge

The requirement for high pressure (ranging from 15 MPa to nearly 80 MPa depending on the stage) adds complexity to the battery system. You are trading simplicity for conductivity. In a laboratory setting, this is managed by heavy presses; in commercial applications, this necessitates robust packaging to maintain that pressure over the vehicle's life.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To optimize your assembly process, assess your primary objective:

- If your primary focus is High-Rate Performance: Apply higher assembly pressures (approx. 74 MPa) to minimize surface roughness and achieve the lowest possible internal resistance for rapid ion transport.

- If your primary focus is Cycle Life & Stability: Ensure the pressure setup allows for continuous, stable compression (In-situ) to accommodate the volumetric "breathing" of the cell without layer separation.

Ultimately, pressure in solid-state assembly is not merely a manufacturing step; it is the active mechanism that bridges the gap between isolated components and a functioning, conductive system.

Summary Table:

| Key Objective | Recommended Pressure | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| High-Rate Performance | ~74 MPa | Minimizes interfacial resistance for fast charging/discharging |

| Cycle Life & Stability | Continuous, in-situ pressure | Maintains contact during electrode expansion/contraction |

| General Assembly | 15 - 80 MPa | Forces rigid solid layers into intimate, void-free contact |

Ready to perfect your solid-state battery assembly?

KINTEK specializes in high-performance lab press machines, including automatic and heated lab presses, designed to deliver the precise, uniaxial pressure required for reliable solid-state battery R&D. Our equipment helps you eliminate microscopic gaps, achieve low-impedance interfaces, and ensure long-term cycling stability.

Contact our experts today to discuss how our presses can optimize your battery development process and bring your laboratory innovations to life.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

- Automatic Lab Cold Isostatic Pressing CIP Machine

- Electric Lab Cold Isostatic Press CIP Machine

- Carbide Lab Press Mold for Laboratory Sample Preparation

People Also Ask

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in solid-state battery research? Enhance Pellet Performance

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in FTIR characterization of silver nanoparticles?

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in sulfide electrolyte pellets? Optimize Battery Densification

- What is the significance of uniaxial pressure control for bismuth-based solid electrolyte pellets? Boost Lab Accuracy

- Why is a laboratory hydraulic press necessary for electrochemical test samples? Ensure Data Precision & Flatness