The Question of "What"

In a laboratory, a factory, or out in the field, one of the most fundamental questions is simply, "What is this made of?"

Answering this requires a conversation with matter itself. We need to excite its atoms and listen carefully to their response. Energy-Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (ED-XRF) is one of our most effective tools for having this conversation.

But its genius isn't just in its ability to ask the question. It's in the speed and clarity with which it understands the answer. This ability stems from a trio of core components working in perfect, simultaneous harmony.

The Anatomy of a Simultaneous System

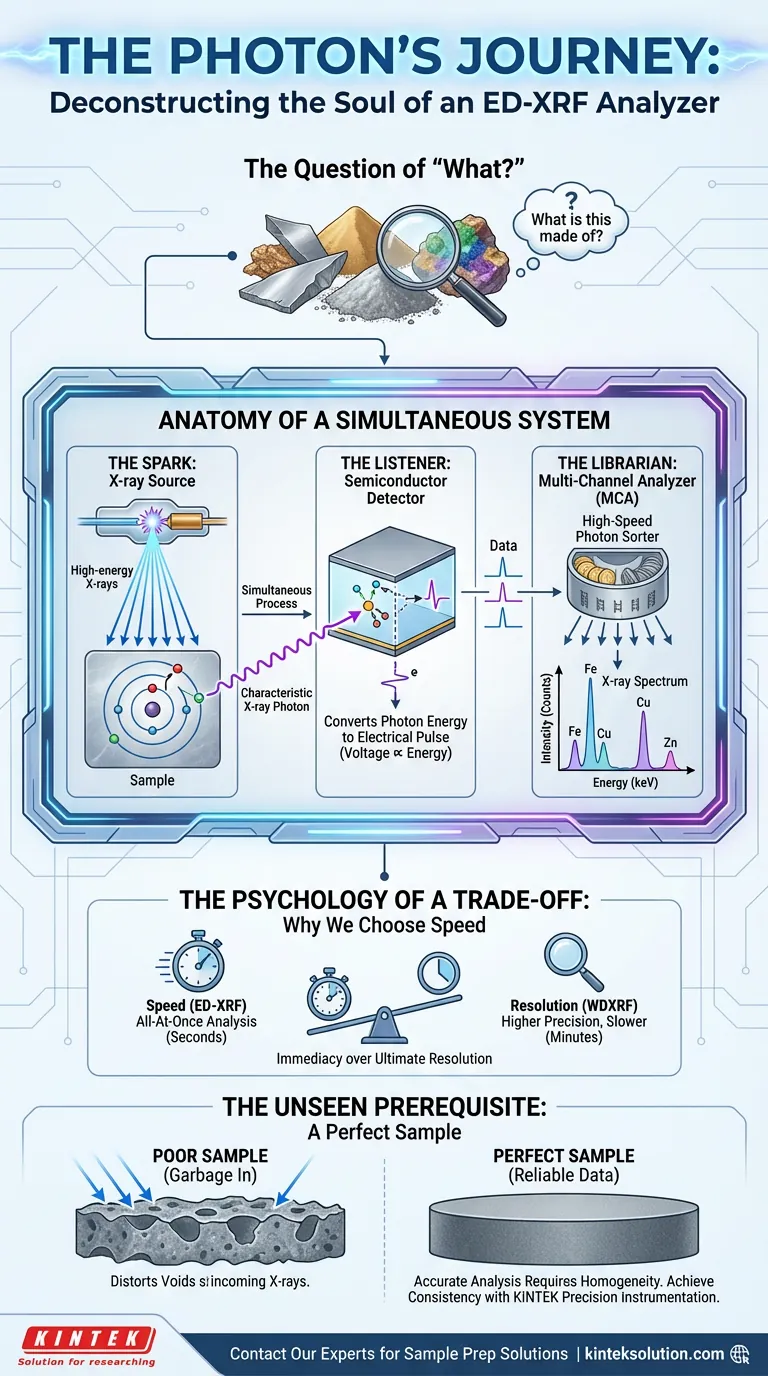

To understand ED-XRF is to understand that it is not a step-by-step, sequential process. It is a system designed to capture an entire elemental fingerprint in a single moment.

This is achieved through an elegant chain of command between three critical components.

The Spark: The X-ray Source

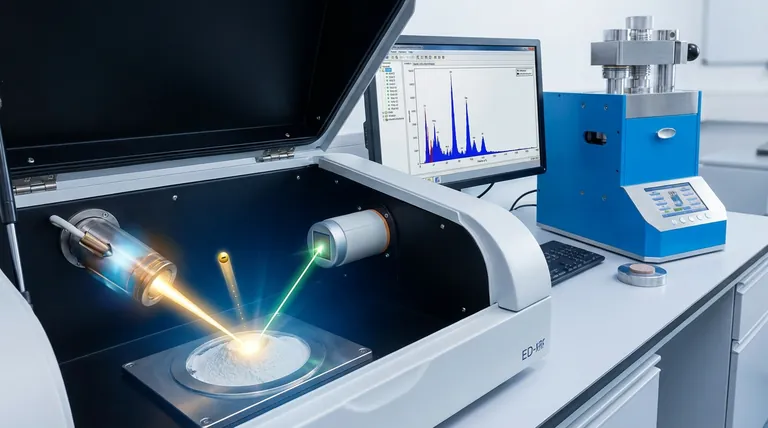

The conversation begins with an interrogation. A miniature X-ray tube, the system's source, bombards the sample with a focused beam of high-energy X-rays.

This is not a gentle tap. It's a jolt of energy designed to dislodge electrons from the deep, inner shells of the sample's atoms. This act of eviction creates a temporary, unstable vacancy.

Nature abhors a vacuum. An electron from a higher-energy outer shell immediately drops to fill the void. In doing so, it releases its excess energy as a secondary X-ray—a fluorescent photon whose energy is the unique, characteristic signature of the element it came from.

The Listener: The Semiconductor Detector

If the source is the interrogator, the semiconductor detector—often a Silicon Drift Detector (SDD)—is the perfect listener. It is the heart of the machine.

When the characteristic X-rays fly out from the sample, they strike the detector. The detector's critical function is not just to count these photons, but to measure the precise energy of each one.

It converts the energy of every single incoming photon into a tiny electrical pulse. The voltage of that pulse is directly proportional to the photon's energy. It's like having perfect pitch; the detector doesn't just hear a noise, it identifies the exact note.

The Librarian: The Multi-Channel Analyzer (MCA)

The detector generates thousands of these voltage pulses in a chaotic stream. The Multi-Channel Analyzer (MCA) is the master librarian that brings order to this chaos.

The MCA rapidly sorts each pulse into one of thousands of discrete bins, or "channels," where each channel corresponds to a very narrow energy range.

Think of it as a high-speed coin sorter for photons. It takes a jumbled bucket of currency and neatly stacks it, giving you a clear count of pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters. The resulting histogram—plotting the number of photons (intensity) versus their energy—is the X-ray spectrum. It is the final, readable answer to our original question.

The Psychology of a Trade-off: Why We Choose Speed

No engineering design is without its compromises. The architecture of ED-XRF is a deliberate choice that favors certain advantages while accepting specific limitations. This reflects a deep understanding of what users often value most: immediacy.

The All-At-Once Advantage

The primary strength of ED-XRF is its simultaneous nature. Because the detector and MCA process all energies at once, a complete elemental analysis can be performed in seconds.

This satisfies a fundamental human and industrial need for rapid feedback. For quality control, material sorting, or preliminary research, the ability to get a comprehensive answer now is often more valuable than getting a perfect answer tomorrow.

The Price of Immediacy

This speed comes at the price of energy resolution. The system's ability to distinguish between two X-rays of very similar energies is inherently lower than its slower, more methodical cousin, Wavelength-Dispersive XRF (WDXRF).

In samples with many elements, this can lead to "peak overlaps," where the signals from two different elements blur together. This isn't a flaw; it's the known trade-off for the system's incredible efficiency and its simpler, more robust, and often portable design.

The Unseen Prerequisite: A Perfect Sample

The entire elegant symphony of the ED-XRF system—the source, detector, and analyzer working in concert—relies on one silent, external partner: the sample itself.

The adage "garbage in, garbage out" has never been more true. The most advanced analyzer in the world can be defeated by a poorly prepared sample. For an XRF analysis to be accurate, the surface it interrogates must be perfectly flat, homogeneous, and representative of the bulk material.

The Foundation of Reliable Data

For powders, soils, and minerals, this means preparing a pressed pellet. The goal is to create a sample with high density and a flawless surface, eliminating particle size effects and surface voids that can distort the X-ray signals. This is not an optional step; it is the foundation upon which reliable data is built.

Achieving this level of consistency manually is difficult. This is where precision instrumentation becomes critical. An automatic lab press, like those engineered by KINTEK, removes the variability and guesswork from sample preparation. It applies precise, repeatable pressure to create ideal pellets every time, ensuring that the data from your XRF analyzer is a true reflection of your material, not an artifact of your preparation method.

From isostatic presses for uniform density to heated presses for polymer analysis, the right preparation tool ensures that the conversation you have with your material is clear and truthful.

Understanding the inner workings of an ED-XRF analyzer reveals a system beautifully optimized for speed. But to fully leverage its power, we must respect the process that comes before the analysis even begins.

If you are looking to ensure the quality and repeatability of your analytical results, the first step is perfecting your sample preparation. Contact Our Experts

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

- Lab Cylindrical Press Mold for Laboratory Use

- Carbide Lab Press Mold for Laboratory Sample Preparation

- Lab Infrared Press Mold for Laboratory Applications

- XRF KBR Steel Ring Lab Powder Pellet Pressing Mold for FTIR

Related Articles

- From Powder to Perfection: The Physics of Trustworthy Analysis

- Beyond Brute Force: The Psychology of Precision in Laboratory Presses

- The Platen's Paradox: Why Bigger Isn't Always Better in Laboratory Presses

- The Architecture of Trust: Why Your Most Important Lab Instrument Isn't an Analyzer

- The Physics of Consistency: How Hydraulic Presses Overcome Human Error