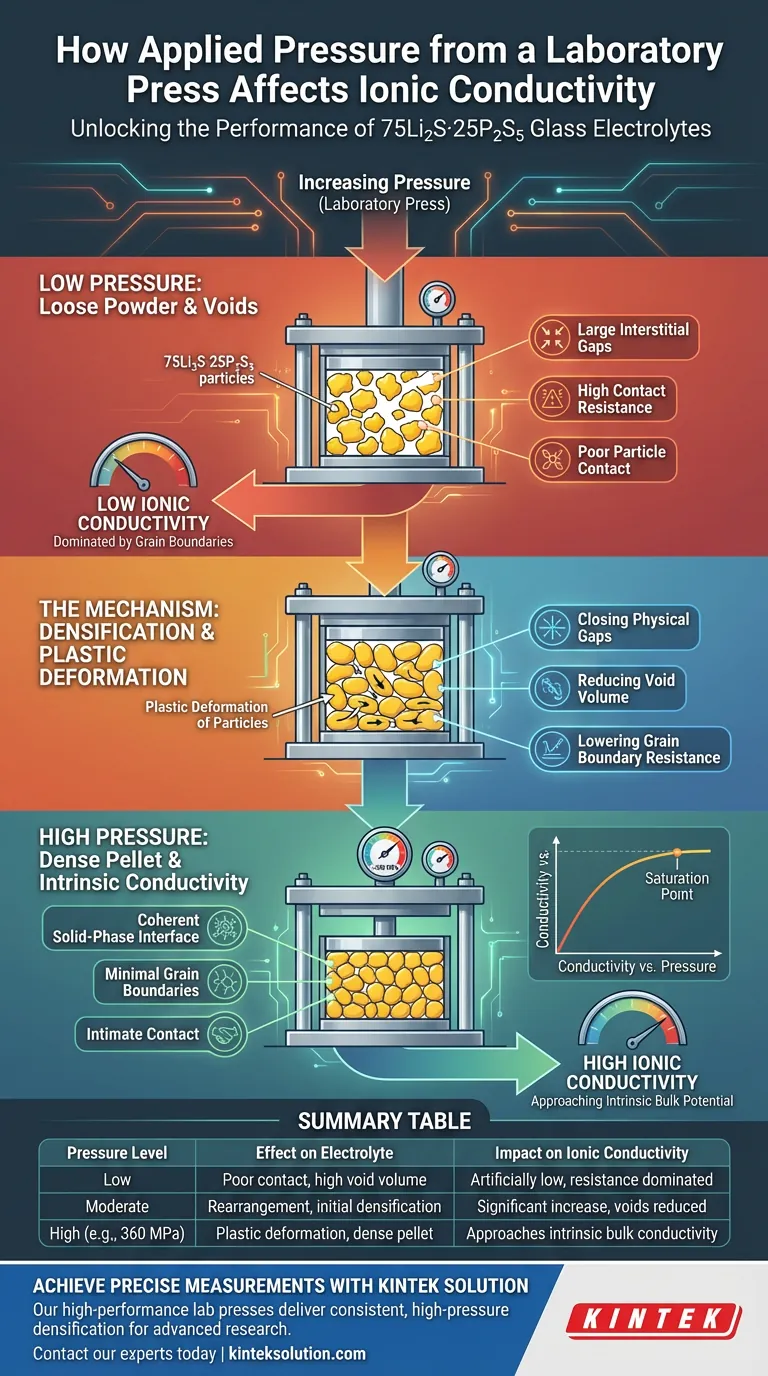

Applied pressure acts as a critical variable for unlocking the performance of 75Li2S·25P2S5 glass electrolytes. Increasing the pressure applied by a laboratory press directly increases the ionic conductivity of the material. This occurs because pressure mechanically forces the electrolyte powder particles into tighter contact, reducing the insulating voids between them and creating a more continuous path for lithium ions to travel.

The application of high pressure drives the plastic deformation of sulfide-based particles, effectively converting a loose powder into a dense pellet. This process eliminates physical gaps and lowers grain boundary resistance, allowing the measured conductivity to approach the material's true intrinsic potential.

The Mechanism of Densification

Closing the Physical Gaps

When the electrolyte is in a loose powder form, significant voids and internal cracks exist between particles.

These voids act as barriers to ion movement. As you increase pressure, you drastically reduce the volume of these empty spaces, forcing particles into intimate contact.

Plastic Deformation of Particles

Sulfide-based electrolytes like 75Li2S·25P2S5 are relatively soft. Under high pressure, they do not just rearrange; they undergo plastic deformation.

This means the particles physically change shape to fill the interstitial gaps. This deformation is essential for creating a coherent, solid-phase interface that mimics a bulk material.

Impact on Electrical Resistance

Reducing Grain Boundary Resistance

The primary impedance in a powder compact usually comes from the "grain boundaries"—the interfaces where particles meet.

Low pressure results in poor contact and high resistance at these boundaries. By applying sufficient force, you drastically decrease grain boundary resistance, which is the most significant factor in boosting the total conductivity of the pellet.

Approaching Intrinsic Conductivity

At lower pressures, your conductivity measurement is often a reflection of how well the powder is packed, rather than the quality of the material itself.

As pressure increases toward high levels (such as 360 MPa), the influence of particle contact fades. At this stage, the measured conductivity begins to reflect the intrinsic bulk conductivity of the 75Li2S·25P2S5 material.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Risk of Under-Pressing

If the applied pressure is too low, the measurement will be dominated by contact resistance.

For example, measuring at pressures below the material's densification threshold may yield artificially low conductivity numbers. This obscures the actual performance of the electrolyte chemistry.

Pressure Magnitude Variance

While the principle of densification is universal, the exact pressure required to reach "saturation" (where conductivity stops increasing) can vary.

Some contexts suggest 60 MPa is sufficient for impedance spectroscopy to reduce voids, while others indicate pressures as high as 360 MPa are needed to fully minimize grain boundary effects in specific pellet fabrications.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To maximize the reliability of your data, align your pressing protocol with your specific objective.

- If your primary focus is material characterization: Apply the highest safe pressure (e.g., up to 360 MPa) to eliminate grain boundary variables and measure the true bulk conductivity of the glass.

- If your primary focus is experimental consistency: Maintain a constant, regulated pressure across all samples to ensure that variations in conductivity are due to material differences, not inconsistencies in pellet density.

Ultimately, high pressure is not merely a manufacturing step but a fundamental requirement for bridging the gap between a resistive powder and a high-performance solid electrolyte.

Summary Table:

| Pressure Level | Effect on Electrolyte | Impact on Ionic Conductivity |

|---|---|---|

| Low Pressure | Poor particle contact, high void volume | Artificially low, dominated by contact resistance |

| Moderate Pressure | Particle rearrangement, initial densification | Significant increase as voids are reduced |

| High Pressure (e.g., 360 MPa) | Plastic deformation, minimal grain boundaries | Approaches intrinsic bulk conductivity of the material |

Ready to achieve precise and reliable ionic conductivity measurements?

KINTEK's high-performance laboratory presses—including automatic, isostatic, and heated models—are engineered to deliver the consistent, high-pressure densification required for advanced solid electrolyte research like your 75Li2S·25P2S5 glass. Our presses ensure you eliminate grain boundary variables and measure true material performance.

Contact our experts today to discuss how our lab press solutions can enhance your solid-state battery development.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

- Laboratory Hydraulic Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

People Also Ask

- What are the advantages of using a laboratory hydraulic press for catalyst samples? Improve XRD/FTIR Data Accuracy

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in solid-state battery research? Enhance Pellet Performance

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in FTIR characterization of silver nanoparticles?

- Why is it necessary to use a laboratory hydraulic press for pelletizing? Optimize Conductivity of Composite Cathodes

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in LLZTO@LPO pellet preparation? Achieve High Ionic Conductivity