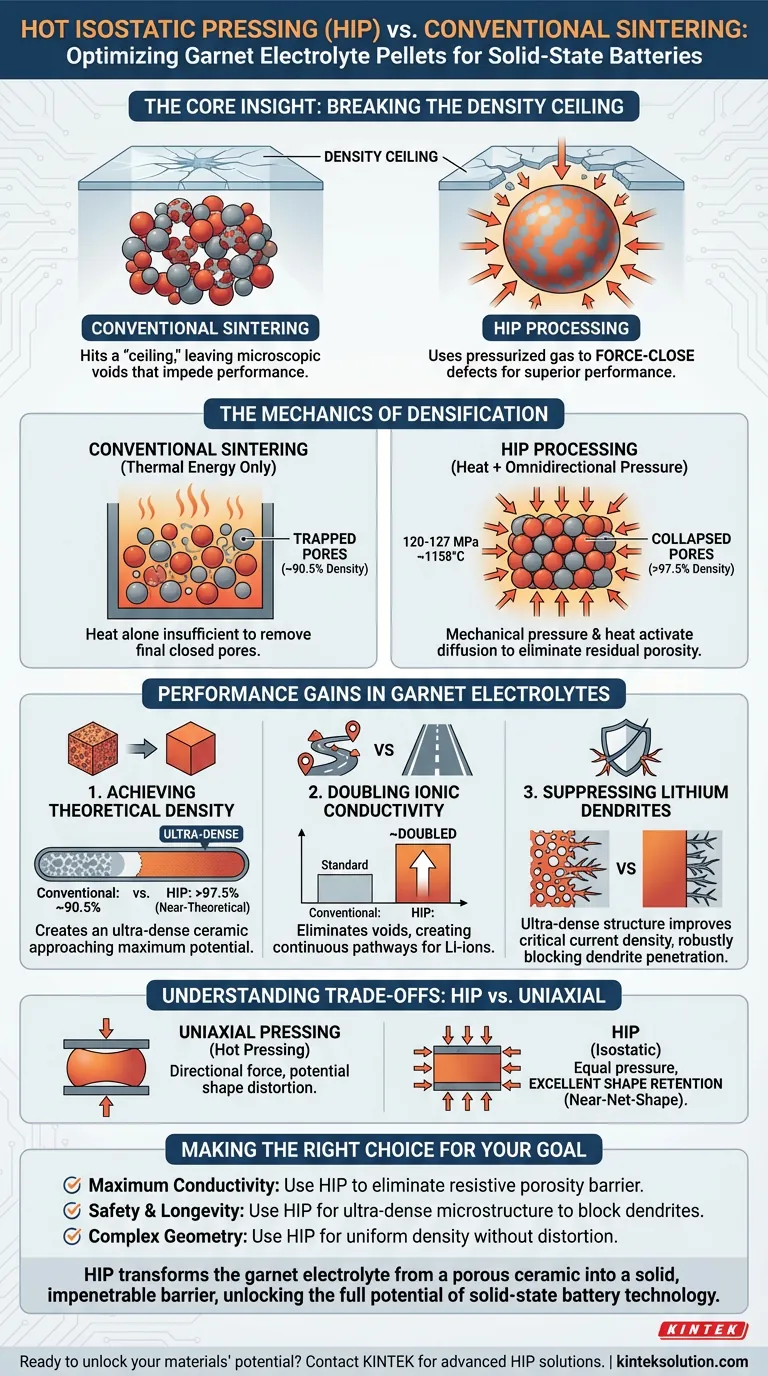

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) distinctively outperforms conventional sintering by applying high temperature and high isostatic gas pressure simultaneously to eliminate residual porosity. While conventional sintering relies primarily on thermal energy to bond particles—often leaving closed pores—HIP utilizes omnidirectional force to mechanically close these voids, achieving near-theoretical density and superior electrochemical performance.

The Core Insight Conventional sintering often hits a "density ceiling," leaving microscopic voids that impede battery performance. HIP breaks through this ceiling by using pressurized gas to force-close these defects, directly translating to higher ionic conductivity and greater resistance to lithium dendrite penetration.

The Mechanics of Densification

Overcoming the Limits of Thermal Energy

Conventional sintering uses heat to encourage particles to bond. However, as the ceramic densifies, pores can become isolated and "trapped" inside the material.

Heat alone is often insufficient to remove these final closed pores. This results in a ceramic body that may only reach ~90% of its potential density.

The Power of Omnidirectional Pressure

HIP introduces a second variable: isostatic pressure. By applying high pressure (e.g., 120–127 MPa) via a gas medium from all directions, the process mechanically forces the material together.

This pressure works in concert with high temperatures (e.g., ~1158°C) to activate plastic deformation and diffusion bonding. This combination effectively collapses the residual pores that conventional sintering cannot resolve.

Performance Gains in Garnet Electrolytes

Achieving Theoretical Density

The primary metric of success in solid electrolytes is relative density. HIP processing can elevate relative density from approximately 90.5% (common in conventional sintering) to 97.5% or higher.

This creates an ultra-dense ceramic body that approaches the material's theoretical maximum density.

Doubling Ionic Conductivity

Porosity acts as a barrier to ion movement. By eliminating voids and tightening grain boundaries, HIP creates a more continuous pathway for lithium ions.

Data indicates that this densification can result in a doubling of ionic conductivity compared to samples processed via standard methods.

Suppressing Lithium Dendrites

A dense microstructure is the first line of defense against battery failure. Pores and defects in conventional ceramics provide pathways for lithium dendrites to penetrate and short-circuit the cell.

The ultra-dense nature of HIP-processed pellets significantly improves the critical current density, making the electrolyte robust enough to suppress dendrite growth.

Understanding the Trade-offs: HIP vs. Uniaxial Pressing

Shape Retention vs. Distortion

It is important to distinguish HIP from "Hot Pressing" (uniaxial). Uniaxial hot pressing applies force from only one direction, which can distort the sample's shape and concentrate stress on convex areas.

Because HIP uses a gas medium to apply pressure equally from every angle, it maintains the initial shape of the material. This allows for "near-net-shape" manufacturing, reducing the need for post-processing and minimizing waste of expensive materials.

Complexity and Material Utilization

While HIP offers superior density, it involves high-pressure equipment that is generally more complex than standard sintering furnaces.

However, for high-value applications, this is offset by high material utilization and the ability to process complex geometries without the use of lubricants or binders that might introduce impurities.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

While conventional sintering is simpler, HIP is the definitive choice when performance cannot be compromised.

- If your primary focus is Maximum Conductivity: Use HIP to eliminate the porosity that acts as a resistive barrier to ion flow.

- If your primary focus is Safety and Longevity: Use HIP to achieve the ultra-dense microstructure required to block lithium dendrite penetration.

- If your primary focus is Complex Geometry: Use HIP to ensure uniform density across irregular shapes without the distortion caused by uniaxial pressing.

HIP transforms the garnet electrolyte from a porous ceramic into a solid, impenetrable barrier, unlocking the full potential of solid-state battery technology.

Summary Table:

| Advantage | Conventional Sintering | HIP Processing |

|---|---|---|

| Relative Density | ~90.5% | >97.5% (Near-Theoretical) |

| Ionic Conductivity | Standard | Doubled |

| Dendrite Resistance | Moderate | Significantly Improved |

| Shape Retention | Good | Excellent (Near-Net-Shape) |

Ready to unlock the full potential of your solid-state battery materials? KINTEK specializes in advanced lab press machines, including heated isostatic presses, designed to help researchers like you achieve the ultra-dense, high-performance garnet electrolytes essential for next-generation batteries. Contact our experts today to discuss how our HIP solutions can enhance your lab's capabilities and accelerate your R&D.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Warm Isostatic Press for Solid State Battery Research Warm Isostatic Press

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory

- Laboratory Split Manual Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

People Also Ask

- What is the purpose of using a warm isostatic press (WIP)? Optimize All-Solid-State Battery Performance

- How does increasing HIP pressure affect Li2MnSiO4 synthesis temperature? Achieve Low-Temp Synthesis

- What is the mechanism of a Warm Isostatic Press (WIP) on cheese? Master Cold Pasteurization for Superior Safety

- How does Warm Isostatic Pressing (WIP) compare to HIP for nanomaterials? Unlock 2 GPa Density with WIP

- What is the typical working temperature for Warm Isostatic Pressing? Optimize Your Material Densification