The application of differential pressure during the assembly of multi-layer all-solid-state batteries is a critical manufacturing strategy designed to balance mechanical integrity with electrochemical efficiency. By applying lower pressure to pre-form sensitive layers (like the separator) and higher pressure to laminate electrode layers, manufacturers prevent material damage while ensuring the intimate, void-free contact necessary for optimal ionic conduction.

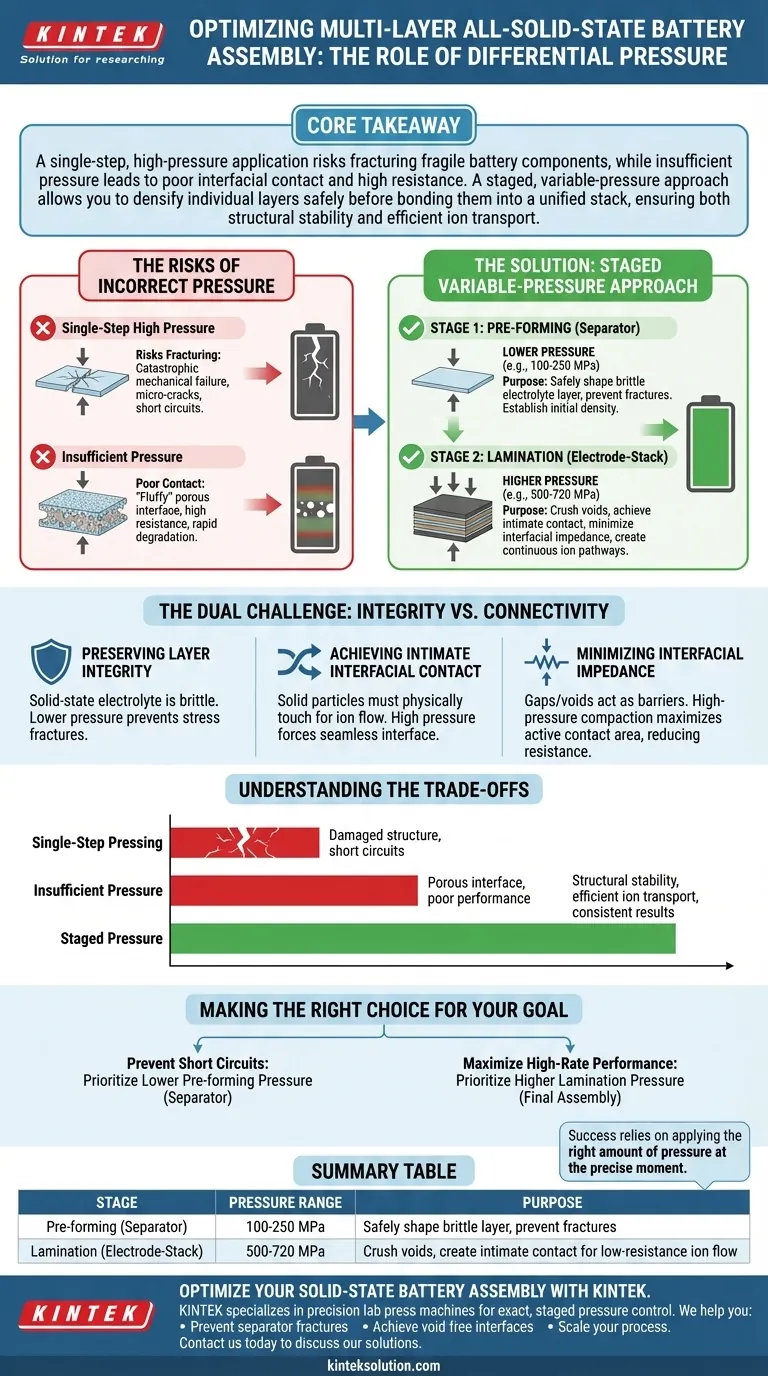

Core Takeaway A single-step, high-pressure application risks fracturing fragile battery components, while insufficient pressure leads to poor interfacial contact and high resistance. A staged, variable-pressure approach allows you to densify individual layers safely before bonding them into a unified stack, ensuring both structural stability and efficient ion transport.

The Dual Challenge: Integrity vs. Connectivity

To understand why variable pressure is necessary, you must look beyond simple assembly. You are solving two conflicting problems simultaneously: protecting fragile materials and forcing solid particles to behave like a continuous medium.

Preserving Layer Integrity

The solid-state electrolyte (separator) is often a rigid, brittle layer.

If you subject this layer to maximum pressure immediately during the initial stacking, you risk catastrophic mechanical failure.

By using a lower pre-forming pressure (e.g., 100 MPa to 250 MPa), you establish the shape and initial density of the separator without introducing stress fractures.

Achieving Intimate Interfacial Contact

Once the separator is safely formed, the priority shifts to conductivity.

Solid-state batteries rely on "intimate contact"—meaning the solid particles of the electrode and electrolyte must physically touch to allow lithium ions to pass.

A significantly higher pressure (e.g., 500 MPa to 720 MPa) is applied during the lamination stage to crush voids and force these distinct layers into a seamless interface.

Minimizing Interfacial Impedance

The ultimate goal of the high-pressure lamination step is to reduce electrical resistance.

Gaps or voids between the cathode and the electrolyte act as barriers to ion flow, drastically reducing battery performance.

High-pressure compaction maximizes the active contact area, creating continuous ion transport pathways that mimic the efficiency of liquid electrolytes.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While staged pressure is superior, it introduces complexity that must be managed carefully.

The Risk of Single-Step Pressing

Attempting to save time by using a single, high-pressure step is a common manufacturing pitfall.

This "monolithic" approach frequently damages the internal structure, causing micro-cracks in the electrolyte that can lead to short circuits.

Furthermore, simultaneous pressing of materials with different yield strengths can result in uneven densification and warping.

The Consequence of Insufficient Pressure

Conversely, being too cautious with pressure application results in a "fluffy" or porous interface.

If the lamination pressure is too low, the solid-solid interface remains weak, leading to high interfacial resistance.

This results in poor capacity utilization and rapid degradation, as ions cannot effectively traverse the boundary between the electrode and the electrolyte.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The specific pressures you choose will depend on your material chemistry and performance targets, but the principle of staged application remains constant.

- If your primary focus is preventing short circuits: Prioritize a lower, gentle pre-forming pressure for the separator layer to ensure no micro-cracks are introduced before lamination.

- If your primary focus is maximizing high-rate performance: Prioritize a higher lamination pressure during the final assembly step to minimize voids and reduce interfacial impedance.

Success in solid-state assembly relies not just on how much pressure you apply, but on applying the right amount at the precise moment the material is ready to receive it.

Summary Table:

| Stage | Pressure Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-forming (Separator) | 100-250 MPa | Safely shape brittle electrolyte layer, prevent fractures |

| Lamination (Electrode-Stack) | 500-720 MPa | Crush voids, create intimate contact for low-resistance ion flow |

Optimize Your Solid-State Battery Assembly with KINTEK

Struggling with interfacial resistance or material failure in your multi-layer battery prototypes? KINTEK specializes in precision lab press machines—including automatic, isostatic, and heated lab presses—designed to deliver the exact, staged pressure control required for reliable solid-state battery R&D and production.

We help you:

- Prevent separator fractures with gentle, precise pre-forming pressures

- Achieve void-free interfaces and minimal impedance through high-pressure lamination

- Scale your process from research to pilot production with consistent, repeatable results

Contact us today to discuss how our lab press solutions can enhance your battery performance and yield. Let's build a more efficient energy future, together.

Get in touch via our Contact Form

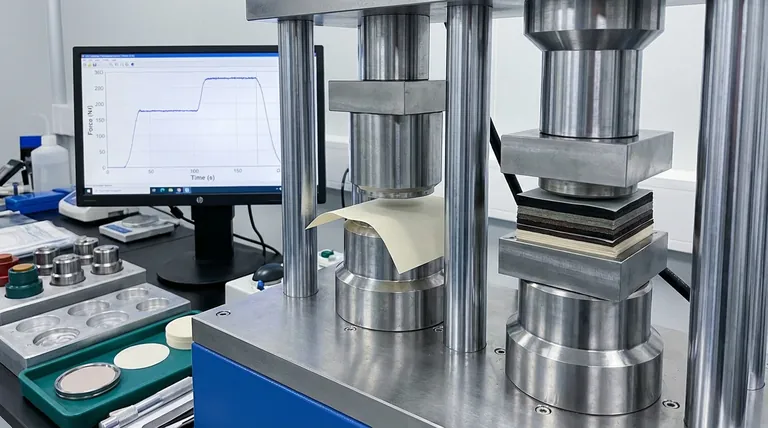

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Lab Hydraulic Press

People Also Ask

- What is the function of a laboratory hydraulic press in sulfide electrolyte pellets? Optimize Battery Densification

- Why use a laboratory hydraulic press with vacuum for KBr pellets? Enhancing Carbonate FTIR Precision

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in LLZTO@LPO pellet preparation? Achieve High Ionic Conductivity

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in FTIR characterization of silver nanoparticles?

- Why is it necessary to use a laboratory hydraulic press for pelletizing? Optimize Conductivity of Composite Cathodes