A laboratory hydraulic press is the fundamental tool used to overcome the physical resistance inherent in solid materials. It applies immense, controlled mechanical force—often ranging from 40 to 250 MPa—to compact powdered electrolytes and electrodes into dense, cohesive pellets. This process, known as cold pressing, transforms loose particles into the solid structural foundation required for a functional battery cell.

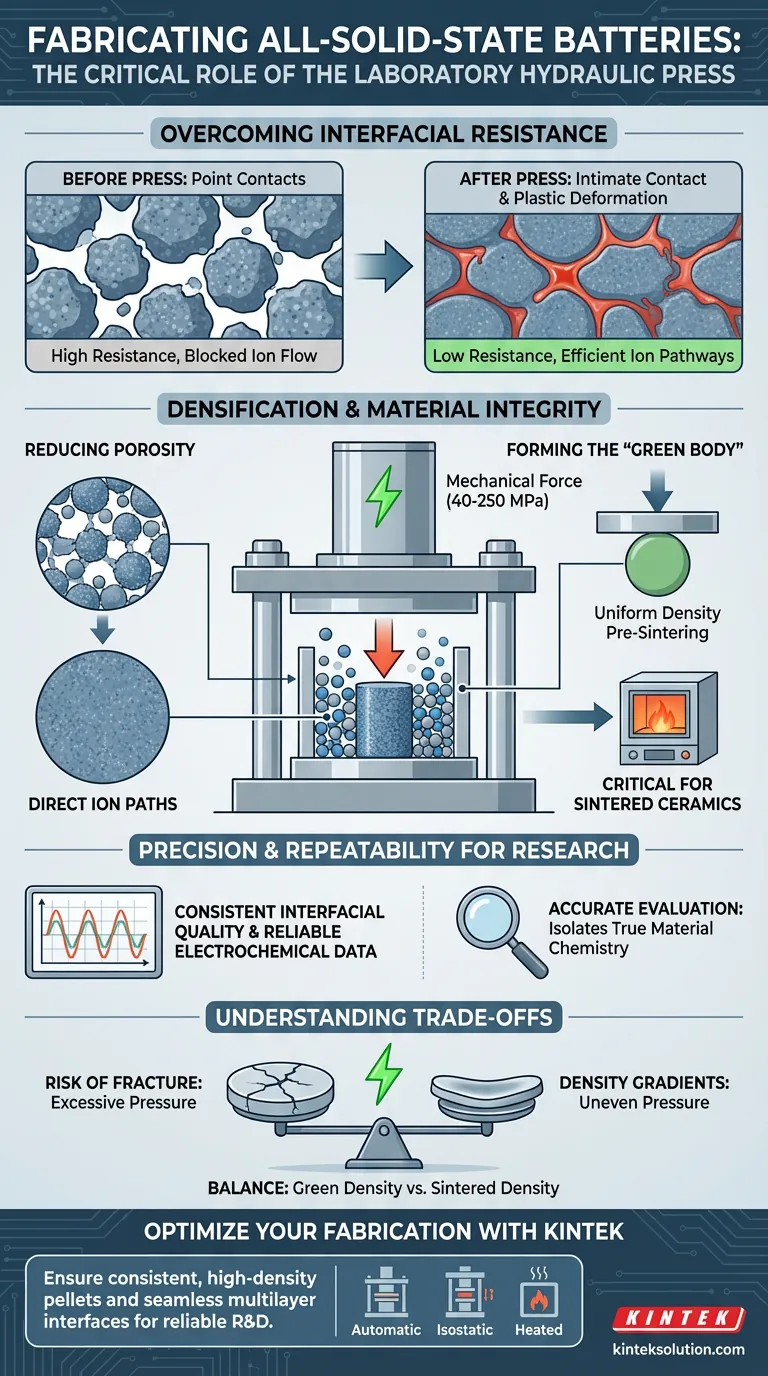

The hydraulic press solves the primary bottleneck of all-solid-state batteries: high interfacial resistance. By mechanically forcing rigid materials into intimate contact and eliminating microscopic voids, it establishes the continuous physical pathways necessary for ions to move efficiently through the cell.

Overcoming the Solid-Solid Interface Challenge

In liquid electrolyte batteries, the liquid naturally wets the electrode surface, creating perfect contact. In all-solid-state batteries, achieving this contact is a significant engineering hurdle.

Eliminating Point Contacts

Rigid components, such as garnet solid electrolytes and metal electrodes, naturally resist bonding. Without significant force, they only touch at microscopic "point contacts."

This limited contact area creates extremely high interfacial resistance, which blocks the flow of ions and degrades battery performance.

Inducing Plastic Deformation

To solve the contact issue, the hydraulic press applies enough pressure to force softer materials to behave like a fluid.

For example, when pressing metallic lithium against a hard ceramic electrolyte, the pressure causes plastic deformation in the lithium. This forces the metal to fill the microscopic voids and roughness on the electrolyte’s surface, maximizing the active area for ion transfer.

Creating Seamless Multilayers

Fabrication often involves stacking different layers, such as a cathode composite onto a solid separator.

A hydraulic press creates a "tight, seamless physical contact" between these distinct layers. This mechanical bonding is critical for lowering the total internal resistance of the multilayered structure.

Densification and Material Integrity

Beyond connecting layers, the hydraulic press is essential for the structural integrity of the individual materials themselves.

Reducing Porosity

Powdered electrolytes naturally contain air gaps and voids, which act as barriers to ion conduction.

By applying high pressure (typically 1.5 to 2 tons in lab settings), the press significantly increases the density of the pellet. This reduction in internal porosity ensures that ions have a direct, uninterrupted path through the material.

Forming the "Green Body"

In ceramic processing, the initial pressed powder is called a "green body."

The magnitude of pressure and the holding time determine the density and strength of this green body. This step is a critical prerequisite for high-temperature sintering; a poorly pressed green body will result in a defective, low-density final ceramic after heating.

The Role of Precision in Research

For a Technical Advisor, the value of a hydraulic press lies not just in force, but in repeatability.

Ensuring Data Consistency

Battery performance is highly sensitive to fabrication variables. Variations in pressure lead to variations in contact area.

If the contact area changes from cell to cell, the electrochemical data (such as impedance spectra) becomes unreliable. A hydraulic press allows researchers to apply the exact same pressure every time, ensuring that the interfacial quality remains constant across different test cells.

Enabling Accurate Evaluation

By controlling the mechanical variables, researchers can isolate the chemical properties of the materials.

This ensures that the data collected reflects the true performance of the battery chemistry, rather than artifacts caused by poor physical assembly or inconsistent hand-pressing.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While essential, the use of hydraulic pressure introduces specific physical limitations that must be managed.

The Risk of Fracture

There is a delicate balance between achieving high density and maintaining structural integrity. Excessive pressure, particularly on brittle ceramic electrolytes, can induce micro-cracks or complete fracture, rendering the separator useless.

Green Density vs. Sintered Density

A common pitfall is assuming that high pressure alone guarantees a perfect final product. While cold pressing creates a dense green body, the final density is achieved during sintering.

If the pressure is applied unevenly or is too high, it can lead to density gradients within the pellet. This causes warping or uneven shrinkage during the subsequent heating phase.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The specific application of the hydraulic press depends on which stage of fabrication you are currently prioritizing.

- If your primary focus is Electrolyte Synthesis: Prioritize pressure protocols that maximize "green body" uniformity to prevent warping during the high-temperature sintering process.

- If your primary focus is Cell Assembly: Focus on applying sufficient pressure to induce plastic deformation in the anode without exceeding the fracture toughness of the ceramic separator.

Ultimately, the laboratory hydraulic press acts as the bridge between theoretical material chemistry and physical reality, converting loose potential into a cohesive, conductive power source.

Summary Table:

| Key Function | Benefit in Battery Fabrication | Typical Pressure Range |

|---|---|---|

| Eliminates Interfacial Resistance | Creates intimate contact between rigid solid electrolytes and electrodes for efficient ion flow. | 40 - 250 MPa |

| Induces Plastic Deformation | Forces softer materials (e.g., lithium) to conform to hard surfaces, maximizing active area. | Varies by material |

| Reduces Internal Porosity | Compacts powdered materials into dense pellets, providing an uninterrupted path for ions. | ~1.5 to 2 tons (lab scale) |

| Ensures Research Repeatability | Applies precise, consistent pressure for reliable and comparable electrochemical data across test cells. | Precisely controlled |

Ready to Optimize Your All-Solid-State Battery Research?

The precise control of a KINTEK laboratory hydraulic press is fundamental to overcoming the physical challenges of solid-state battery fabrication. By ensuring consistent, high-density pellets and seamless multilayer interfaces, our presses enable you to generate reliable data and accelerate your R&D cycle.

KINTEK specializes in robust and reliable lab press machines—including automatic, isostatic, and heated lab presses—designed to meet the exacting demands of advanced battery development.

Contact our experts today to discuss how a KINTEK hydraulic press can become a cornerstone of your laboratory's capabilities.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Lab Hydraulic Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press for XRF KBR FTIR Lab Press

People Also Ask

- What are the steps for assembling a manual hydraulic pellet press? Master Sample Prep for Accurate Lab Results

- What safety features are included in manual hydraulic pellet presses? Essential Mechanisms for Operator and Equipment Protection

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in solid-state battery electrolyte preparation? Achieve Superior Densification and Performance

- What are the advantages of using a hydraulic press for pellet production? Achieve Consistent, High-Quality Samples

- What are the key features of manual hydraulic pellet presses? Discover Versatile Lab Solutions for Sample Prep