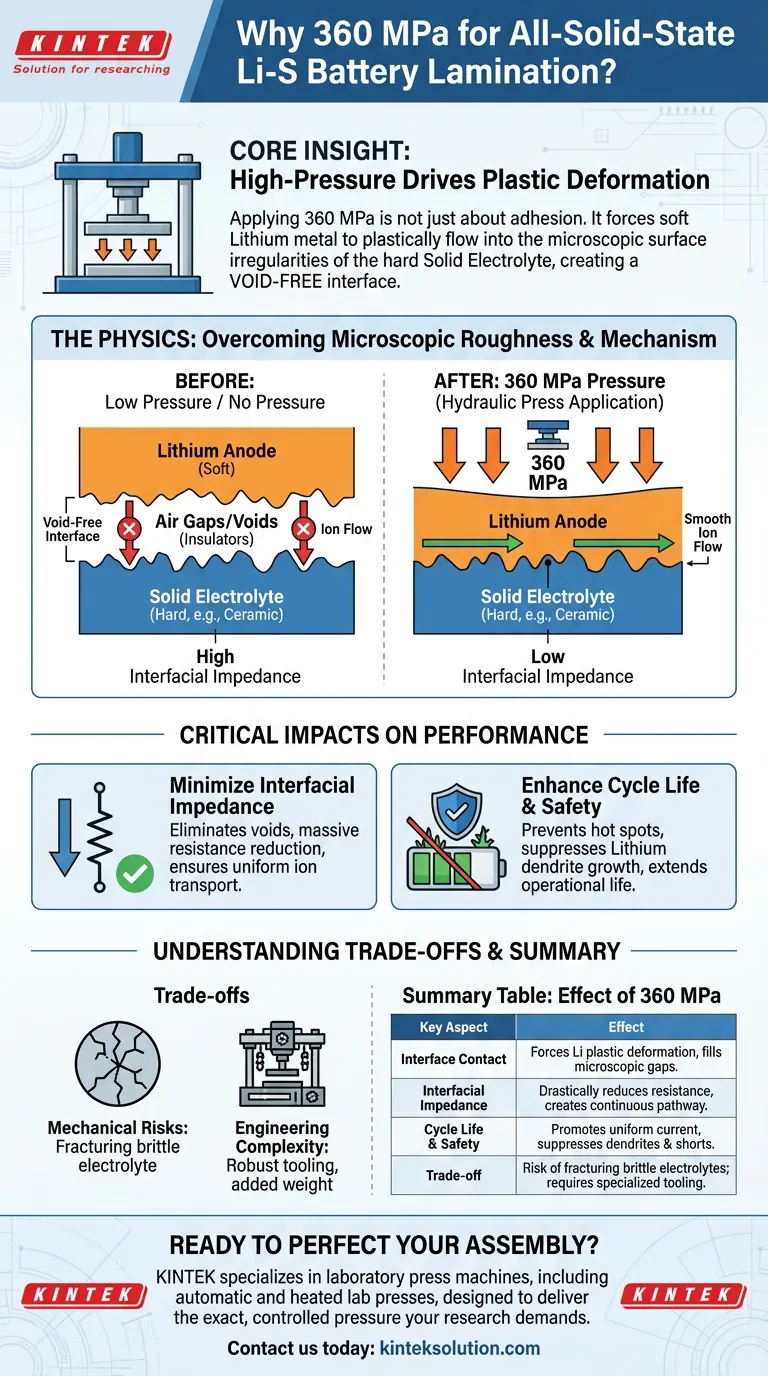

High-pressure lamination drives the plastic deformation of the lithium metal anode. In an all-solid-state lithium-sulfur battery, applying 360 MPa is not merely about adhesion; it forces the soft lithium metal to physically flow into the microscopic surface irregularities of the hard solid electrolyte, creating a void-free interface.

Core Insight Solids do not naturally form perfect interfaces; microscopic roughness creates air gaps that block ion flow. The application of 360 MPa eliminates these voids by mechanically interlocking the anode and electrolyte, drastically reducing interfacial impedance and enabling the uniform current distribution required for safety and longevity.

The Physics of the Solid-Solid Interface

Overcoming Microscopic Roughness

Unlike liquid electrolytes that flow into porous electrodes, solid-state components are rigid. Even surfaces that appear smooth to the naked eye possess microscopic peaks and valleys.

Without high pressure, the anode and electrolyte only touch at the "peaks" of their surfaces. This results in minimal effective contact area and high resistance to ion transport.

The Mechanism of Plastic Deformation

Lithium metal is relatively soft, while solid-state electrolytes (like ceramics) are generally hard. The 360 MPa pressure leverages this hardness differential.

Under this specific load, the lithium metal surpasses its yield strength and undergoes plastic deformation. It effectively "creeps" or flows, filling the pores and valleys of the electrolyte surface to establish intimate, continuous physical contact.

Critical Impacts on Performance

Minimizing Interfacial Impedance

The primary barrier to solid-state battery performance is high interfacial impedance (resistance). The presence of voids acting as insulators creates a bottleneck for lithium ions.

By eliminating these gaps through high-pressure lamination, the system achieves a massive reduction in resistance—potentially dropping from hundreds of Ohms to double digits. This ensures smooth, uniform transport of lithium ions between the anode and the electrolyte.

Enhancing Cycle Life and Safety

Uniform contact is vital for preventing "hot spots" where current density becomes dangerously high. Uneven current distribution often leads to the growth of lithium dendrites.

Dendrites are metallic filaments that can penetrate the electrolyte and cause internal short circuits. By creating a seamless interface via high pressure, you promote uniform plating and stripping of lithium, suppressing dendrite growth and extending the battery's operational life.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Mechanical Integrity Risks

While high pressure is necessary for contact, it introduces mechanical stress. Excessive or unevenly applied pressure can fracture brittle solid electrolyte layers, particularly ceramic ones like LLZO.

Engineering Complexity

Maintaining such high pressures requires specialized tooling, such as hydraulic presses and robust cell casings. This adds weight and complexity to the battery pack design, as the pressure must often be maintained during operation, not just during initial assembly.

Making the Right Choice for Your Assembly

Applying the correct pressure is a balancing act between minimizing resistance and preserving structural integrity.

- If your primary focus is reducing internal resistance: Prioritize maximizing the lamination pressure to the upper limit of your electrolyte's structural tolerance to ensure 100% active area contact.

- If your primary focus is manufacturing yield: Implement a multi-step pressing protocol (pre-forming at lower pressure, then laminating at high pressure) to reduce the risk of cracking the electrolyte.

Ultimately, the 360 MPa pressure serves as the "activator" for the battery, transforming two separate solids into a unified electrochemical system capable of high-rate performance.

Summary Table:

| Key Aspect | Effect of 360 MPa Pressure |

|---|---|

| Interface Contact | Forces lithium to plastically deform, filling microscopic gaps on the electrolyte surface. |

| Interfacial Impedance | Drastically reduces resistance by creating a void-free, continuous ion transport pathway. |

| Cycle Life & Safety | Promotes uniform current distribution, suppressing lithium dendrite growth and short circuits. |

| Trade-off | Risk of fracturing brittle ceramic electrolytes; requires specialized tooling and robust cell design. |

Ready to perfect your solid-state battery assembly process?

The precise, high-pressure lamination described is critical for R&D and production success. KINTEK specializes in laboratory press machines, including automatic and heated lab presses, designed to deliver the exact, controlled pressure your research demands.

Our equipment helps researchers like you achieve the perfect solid-solid interfaces necessary for developing safer, higher-performance batteries. Contact us today to discuss how our presses can enhance your lab's capabilities and accelerate your development cycle.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Lab Hydraulic Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

People Also Ask

- Why use a laboratory hydraulic press with vacuum for KBr pellets? Enhancing Carbonate FTIR Precision

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in LLZTO@LPO pellet preparation? Achieve High Ionic Conductivity

- What are the advantages of using a laboratory hydraulic press for catalyst samples? Improve XRD/FTIR Data Accuracy

- Why is a laboratory hydraulic press used for FTIR of ZnONPs? Achieve Perfect Optical Transparency

- What is the significance of uniaxial pressure control for bismuth-based solid electrolyte pellets? Boost Lab Accuracy