The primary purpose of applying high pressure with a laboratory hydraulic press is to force the cathode, solid electrolyte, and anode layers into a single, highly dense structure. This process eliminates microscopic voids between particles to create intimate "atom-level" contact, which is the fundamental requirement for ions to move efficiently through the battery.

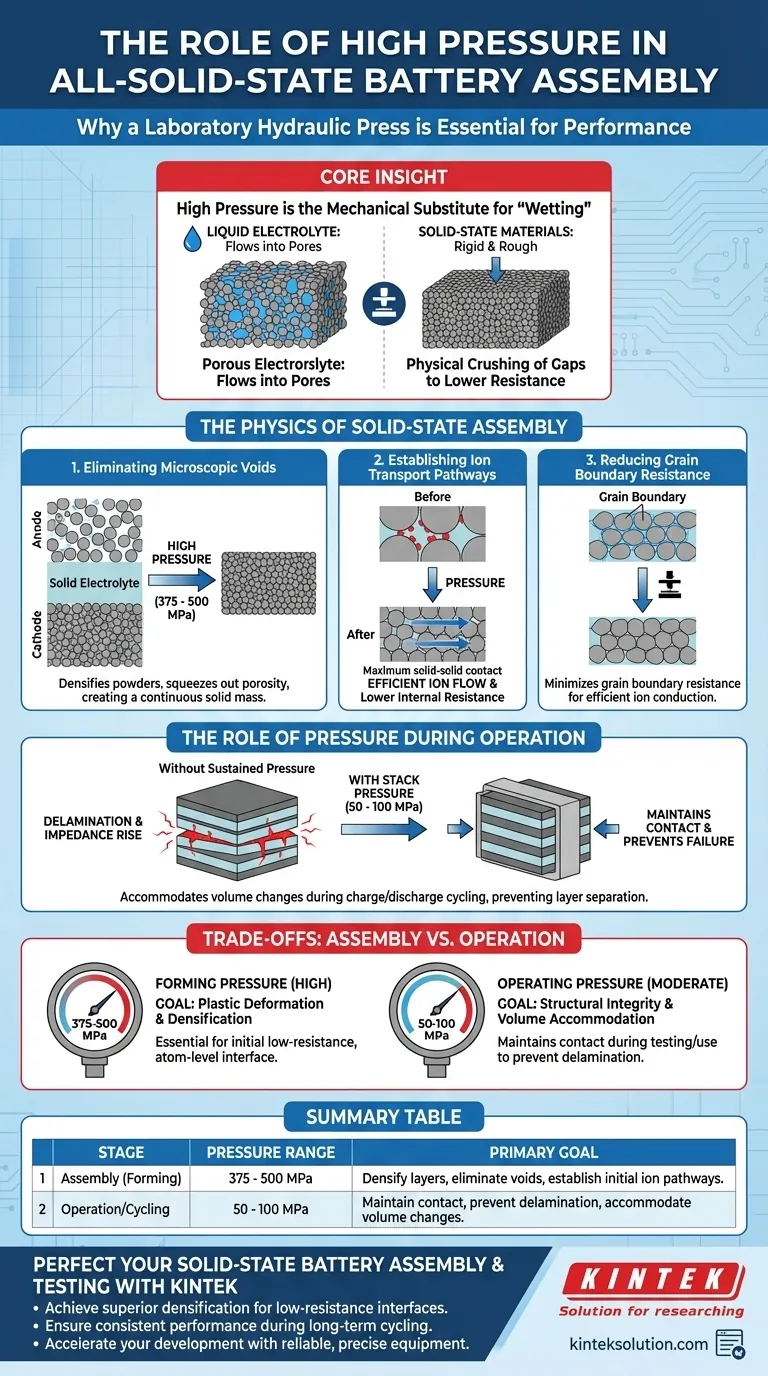

The Core Insight Unlike liquid electrolytes, which naturally flow into pores to create contact, solid-state materials are rigid and rough. High pressure is the mechanical substitute for "wetting," physically crushing gaps to lower resistance and enable the battery to function.

The Physics of Solid-State Assembly

Eliminating Microscopic Voids

When solid electrolyte and electrode powders are stacked, they naturally contain air gaps and pores. These voids act as insulators, blocking the flow of ions.

Applying high cold-pressing pressure (often between 375 MPa and 500 MPa) densifies these powders. This compacts the material, effectively squeezing out porosity to create a continuous solid mass.

Establishing Ion Transport Pathways

For a solid-state battery to operate, lithium ions must physically jump from one particle to the next.

High pressure maximizes the solid-solid contact area at the interfaces between layers. This creates the continuous pathways necessary for ion transport, directly lowering the internal resistance (impedance) of the cell.

Reducing Grain Boundary Resistance

Resistance doesn't just occur between the distinct layers (e.g., anode and electrolyte); it also occurs between individual powder particles within a single layer.

High-pressure densification ensures intimate contact between individual grains of material, such as Li-argyrodite. This minimizes grain boundary resistance, allowing the electrolyte pellet to conduct ions as efficiently as possible.

The Role of Pressure During Operation

Maintaining Contact During Cycling

Creating a dense pellet is only the first step; maintaining that density is equally critical.

During charge and discharge cycles, electrode materials naturally expand and contract (volume changes). Without sustained pressure, these shifts can cause the layers to separate or delaminate.

Preventing Impedance Rise

Maintaining a constant "stack pressure" (typically lower than assembly pressure, e.g., 50 MPa to 100 MPa) acts as a containment force.

This external pressure accommodates volumetric changes while forcing the layers to stay in contact. This prevents the rapid increase in interfacial resistance that leads to battery failure.

Understanding the Trade-offs: Assembly vs. Operation

It is critical to distinguish between the forming pressure used during manufacturing and the operating pressure used during testing.

The Forming Pressure (High)

During initial assembly, extreme pressures (up to 500 MPa) are required to plastically deform the particles and eliminate voids. Failure to apply sufficient pressure here results in a porous, high-resistance cell that creates a bottleneck for high-rate performance.

The Operating Pressure (Moderate)

During testing or use, the pressure must be maintained but acts differently. Here, the goal is structural integrity and accommodation of volume change.

Using a consistent operating pressure (e.g., 50-100 MPa) simulates real-world packaging conditions. However, users must ensure this pressure is applied uniformly to avoid localized stress points that could damage the rigid electrolyte.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To achieve optimal results with your laboratory press, you must tailor the pressure application to your specific stage of development.

- If your primary focus is Assembly (Densification): Apply high pressure (375–500 MPa) to crush voids and establish the initial low-resistance, atom-level interface.

- If your primary focus is Cycle Life Testing: Maintain a constant, moderate stack pressure (50–100 MPa) to prevent delamination caused by volume expansion during charge/discharge.

Success in solid-state batteries relies not just on the chemistry, but on the mechanical force used to merge distinct solids into a unified electrochemical system.

Summary Table:

| Stage | Pressure Range | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly (Forming) | 375 - 500 MPa | Densify layers, eliminate voids, and establish initial ion pathways. |

| Operation/Cycling | 50 - 100 MPa | Maintain contact, prevent delamination, and accommodate volume changes during charge/discharge. |

Ready to perfect your solid-state battery assembly and testing?

The precise application of pressure is critical for developing high-performance, durable solid-state batteries. KINTEK specializes in laboratory press machines, including automatic and heated lab presses, designed to deliver the exact, uniform pressure required for your R&D.

Our expertise helps you:

- Achieve superior densification for low-resistance interfaces.

- Ensure consistent performance during long-term cycle testing.

- Accelerate your development timeline with reliable, precise equipment.

Contact us today to discuss how our lab presses can meet your specific battery development needs. Get in touch via our contact form and let's power your innovation.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Machine

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Lab Hydraulic Press

People Also Ask

- Why is a laboratory hydraulic press necessary for electrochemical test samples? Ensure Data Precision & Flatness

- Why use a laboratory hydraulic press with vacuum for KBr pellets? Enhancing Carbonate FTIR Precision

- Why is a laboratory hydraulic press used for FTIR of ZnONPs? Achieve Perfect Optical Transparency

- What are the advantages of using a laboratory hydraulic press for catalyst samples? Improve XRD/FTIR Data Accuracy

- What is the role of a laboratory hydraulic press in FTIR characterization of silver nanoparticles?