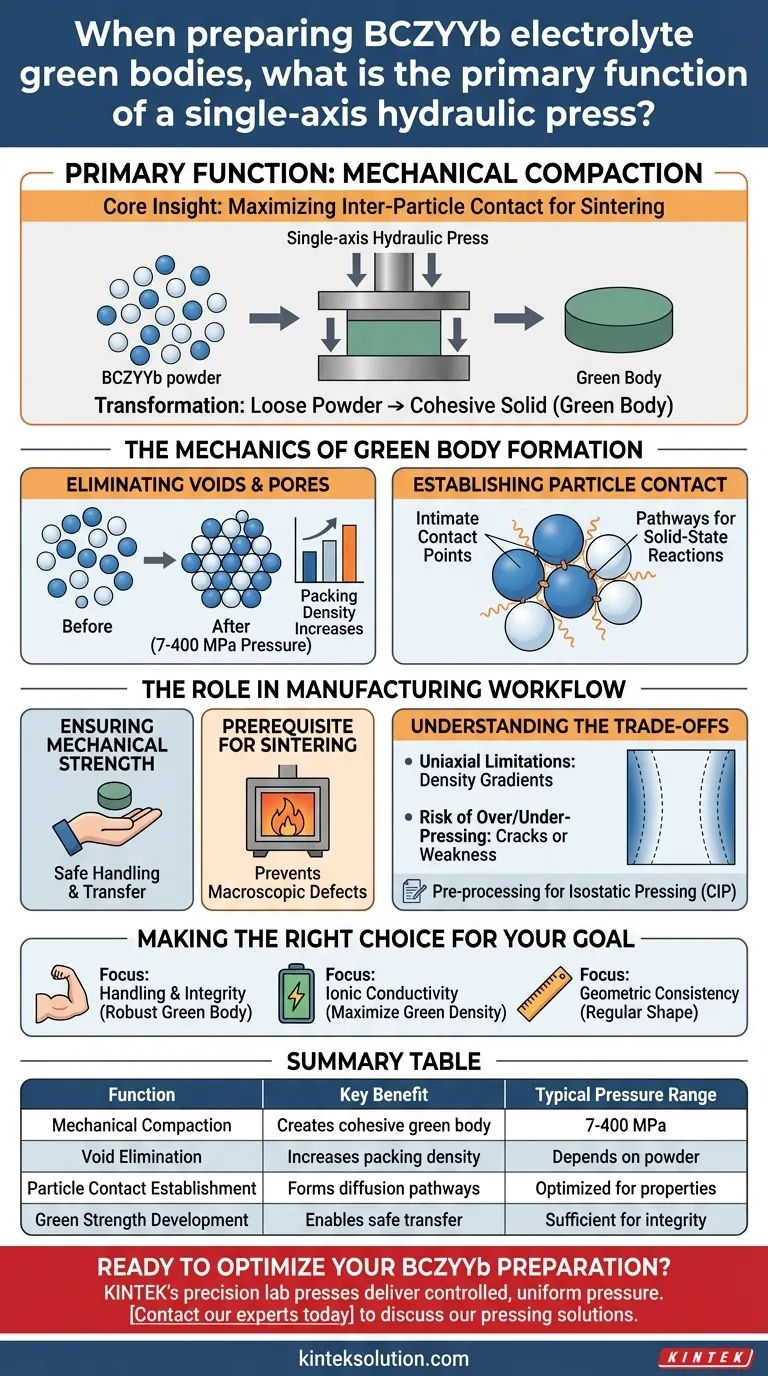

The primary function is mechanical compaction. A single-axis hydraulic press applies controllable, uniform pressure to loose BCZYYb powder, transforming it into a cohesive solid known as a "green body." This process eliminates large pores and establishes the initial structural density required for the material to be safely handled and processed further.

Core Insight: While the visible output is a shaped pellet, the critical engineering objective is maximizing inter-particle contact. By mechanically forcing powder particles together, the press creates the necessary physical foundation for diffusion and densification to occur during the subsequent high-temperature sintering stage.

The Mechanics of Green Body Formation

Eliminating Voids and Pores

Loose BCZYYb powder naturally contains significant air gaps and spacing between particles. The hydraulic press applies force (often ranging from 7 MPa to 400 MPa depending on the specific protocol) to drastically reduce these voids.

This reduction in porosity increases the packing density of the material. A higher packing density is essential for minimizing shrinkage and preventing deformation during later heating stages.

Establishing Particle Contact

For a ceramic electrolyte to function, the particles must eventually fuse into a single, dense entity. The press forces particles to rearrange and pack tightly, creating intimate contact points.

These contact points are the pathways through which solid-state reactions occur. Without this tight packing, the sintering process cannot effectively close the remaining gaps, leading to a porous, low-performance electrolyte.

The Role in Manufacturing Workflow

Ensuring Mechanical Strength

A "green body" is effectively an unsintered ceramic—it is fragile. The press must apply enough pressure to give the pellet sufficient green strength.

This strength allows researchers and engineers to remove the sample from the mold, transfer it to a furnace, or vacuum-seal it without the pellet crumbling or cracking under its own weight.

Prerequisite for Sintering

The pressing stage is not an isolated event; it is a fundamental prerequisite for sintering.

If the green density is too low, the final product will likely suffer from low ionic conductivity. A well-pressed green body significantly reduces the risk of macroscopic defects, such as cracking, during the high-temperature treatment.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Uniaxial Limitations

While a single-axis press is excellent for creating simple shapes like pellets, it applies pressure from one direction. This can sometimes lead to density gradients, where the edges of the pellet are denser than the center due to wall friction.

The Risk of Over- or Under-Pressing

Precision is vital. Insufficient pressure results in a weak body that crumbles during handling. Conversely, excessive pressure can cause lamination or internal stresses that manifest as cracks when the pressure is released.

Pre-processing for Isostatic Pressing

In high-performance workflows, the single-axis press acts only as a preliminary step. It forms a shape robust enough to withstand Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP), where even higher hydrostatic pressures are applied to achieve supreme uniformity.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To maximize the effectiveness of your BCZYYb preparation, align your pressing strategy with your ultimate performance metrics:

- If your primary focus is Handling and Integrity: Ensure your pressure is sufficient to create a robust green body that does not dust or crumble when removed from the die.

- If your primary focus is Ionic Conductivity: Prioritize maximizing green density to ensure intimate particle contact, as this directly influences the final density and performance of the sintered electrolyte.

- If your primary focus is Geometric Consistency: Use the press to define a regular, defect-free shape to minimize warping or deformation during the sintering phase.

The single-axis press is the bridge between raw synthesis and finished ceramic; its proper use is the defining factor in achieving a dense, highly conductive electrolyte.

Summary Table:

| Function | Key Benefit | Typical Pressure Range |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Compaction | Creates cohesive green body for handling | 7 MPa to 400 MPa |

| Void Elimination | Increases packing density, reduces shrinkage | Depends on powder characteristics |

| Particle Contact Establishment | Forms pathways for solid-state diffusion | Optimized for material properties |

| Green Strength Development | Enables safe transfer to sintering furnace | Sufficient for structural integrity |

Ready to optimize your BCZYYb electrolyte preparation? KINTEK's precision lab presses deliver the controlled, uniform pressure needed to achieve maximum green density and superior ionic conductivity in your ceramic electrolytes. Our automatic lab presses, isostatic presses, and heated lab presses are engineered specifically for laboratory research and development. Contact our experts today to discuss how our pressing solutions can enhance your ceramic manufacturing workflow and improve your final product performance.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Lab Hydraulic Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Machine for Glove Box

People Also Ask

- What is the primary function of a laboratory hydraulic press when preparing solid electrolyte pellets? Achieve Accurate Ionic Conductivity Measurements

- What pressure range is recommended for pellet preparation? Achieve Perfect Pellets for Accurate Analysis

- What safety precautions should be taken when operating a hydraulic pellet press? Ensure Safe and Efficient Lab Operations

- What is the purpose of using a laboratory hydraulic press to compact LATP powder into a pellet? Achieve High-Density Solid Electrolytes

- Why is a high-precision laboratory hydraulic press necessary for high-entropy spinel electrolytes? Optimize Synthesis