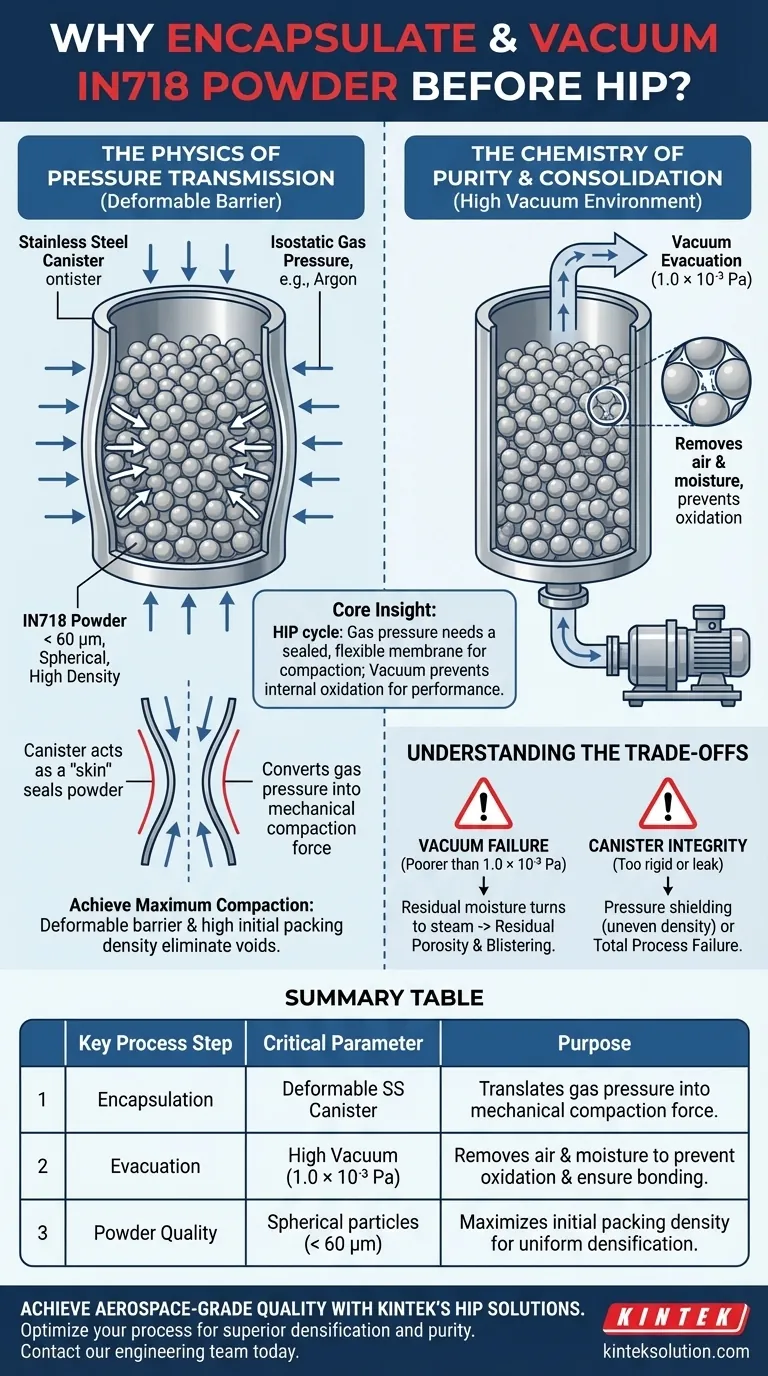

Encapsulating IN718 powder in a stainless steel canister and evacuating it is the defining mechanism that allows Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) to function. The canister serves as a deformable barrier that translates isostatic gas pressure into mechanical compaction force, while the high vacuum ensures the interstitial spaces between particles are free of air and moisture to prevent oxidation.

Core Insight: In a HIP cycle, gas pressure alone cannot densify a porous powder bed because gas permeates the voids; it requires a sealed, flexible membrane to convert that pressure into a crushing force. Simultaneously, the vacuum environment is the only defense against internal oxidation, which would otherwise compromise the superalloy's mechanical performance.

The Physics of Pressure Transmission

Creating a Deformable Barrier

The argon gas typically used in HIP exerts equal pressure in all directions. However, without a physical barrier, this gas would simply penetrate the gaps between the powder particles.

The stainless steel canister acts as a "skin" that seals the powder. Because the canister is softer than the consolidation pressure, it yields and deforms, effectively transmitting the external isostatic pressure uniformly into the powder bed.

Achieving Maximum Compaction

To achieve full density, the powder particles must be mechanically forced together to eliminate voids.

This compaction relies on the initial packing density of the powder. Using highly spherical IN718 powder (under 60 micrometers) creates a high-density starting point, allowing the canister to compress the material with minimal movement and maximum efficiency.

The Chemistry of Purity and Consolidation

Eliminating Atmospheric Contamination

Air trapped within the powder bed contains oxygen and moisture. Upon heating, these elements react chemically with the metal.

The evacuation process, specifically reaching a high vacuum of 1.0 × 10⁻³ Pa, completely removes air and moisture from the inter-particle gaps. This step effectively sterilizes the internal environment of the canister before the heating cycle begins.

Preventing Oxide Formation

IN718 is a high-performance superalloy, but it is susceptible to oxidation at elevated temperatures.

If oxygen remains in the canister, oxides form on the surface of the powder particles during the thermal cycle. These oxide layers prevent particles from bonding (diffusion bonding) properly, resulting in a final component with poor mechanical properties and structural weaknesses.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Risk of Vacuum Failure

The vacuum process is absolute; there is no margin for error. If the vacuum level is insufficient (poorer than 1.0 × 10⁻³ Pa), moisture remains.

This residual moisture turns into steam at high temperatures, creating internal pressure that opposes the compaction force. This leads to residual porosity and potential blistering in the final part.

Canister Integrity vs. Deformability

The canister must be strong enough to handle handling and evacuation, yet pliable enough to deform under pressure.

If the canister design is too rigid, it may shield the powder from the full force of the HIP pressure (pressure shielding), resulting in uneven density near the container walls. Conversely, a leak in the canister allows pressure equalization, causing total process failure.

Ensuring Process Success for IN718

To guarantee the integrity of your superalloy components, align your process controls with your specific quality targets:

- If your primary focus is mechanical purity: Prioritize the evacuation cycle, ensuring the system reaches 1.0 × 10⁻³ Pa to eliminate all potential for oxide inclusion.

- If your primary focus is full densification: Ensure the input powder is spherical and under 60 micrometers to maximize packing density before the canister is even sealed.

By strictly controlling the vacuum environment and the encapsulation integrity, you transform loose powder into a fully dense, aerospace-grade component.

Summary Table:

| Key Process Step | Critical Parameter | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Encapsulation | Deformable Stainless Steel Canister | Translates isostatic gas pressure into mechanical compaction force. |

| Evacuation | High Vacuum (1.0 × 10⁻³ Pa) | Removes air and moisture to prevent internal oxidation and ensure proper particle bonding. |

| Powder Quality | Spherical particles (< 60 µm) | Maximizes initial packing density for efficient and uniform densification. |

Achieve Aerospace-Grade Quality with Your HIP Process

Ensuring the integrity of your IN718 components requires precise control over encapsulation and evacuation. KINTEK specializes in advanced laboratory press machines, including isostatic presses and heated lab presses, designed to deliver the consistent performance and reliability your R&D and production demand.

Let our expertise help you optimize your HIP parameters for superior densification and material purity. Contact our engineering team today to discuss your specific laboratory needs.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory

- Laboratory Split Manual Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

People Also Ask

- What is a heated hydraulic press and what are its main components? Discover Its Power for Material Processing

- Why is a hydraulic heat press critical in research and industry? Unlock Precision for Superior Results

- How does using a hydraulic hot press at different temperatures affect the final microstructure of a PVDF film? Achieve Perfect Porosity or Density

- How are heated hydraulic presses applied in the electronics and energy sectors? Unlock Precision Manufacturing for High-Tech Components

- Why is a heated hydraulic press essential for Cold Sintering Process (CSP)? Synchronize Pressure & Heat for Low-Temp Densification