The Analyst's Dilemma: Trusting the Signal

An analyst stares at two conflicting readings from the same batch of material. The multi-million dollar spectrometer is perfectly calibrated. The methodology is flawless. Yet, the data tells two different stories.

This scenario is unsettlingly common. We place immense faith in our advanced analytical instruments, but often ignore a more fundamental variable: the physical state of the sample itself. We assume a scoop of powder is a reliable narrator, when in reality, it's a landscape of chaos.

Before we can measure a material's chemical truth, we must first conquer its physical inconsistencies.

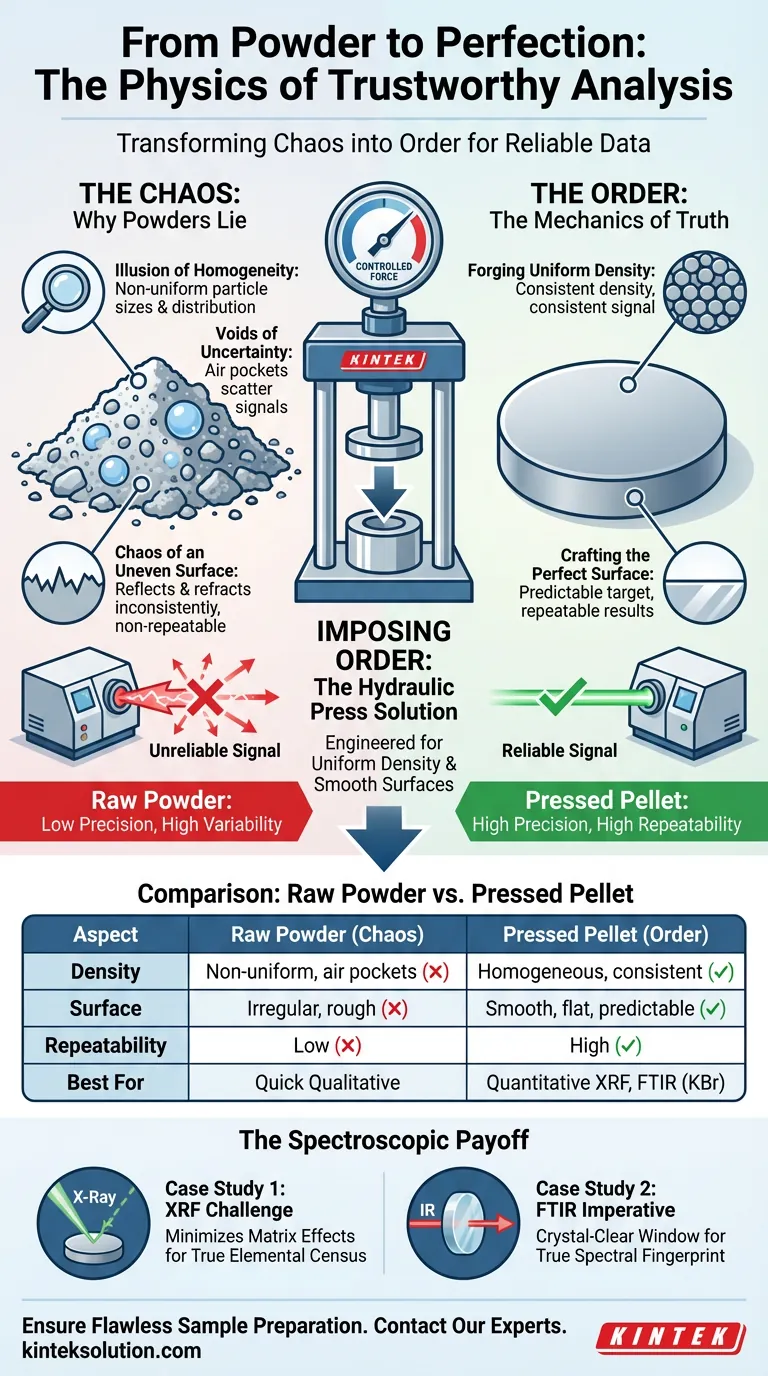

The Unseen Enemy: Why Powders Lie

A loose powder is an inherently unreliable medium for high-precision analysis. Its physical structure is riddled with variables that act as "noise," distorting the very signal we're trying to measure.

The Illusion of Homogeneity

A container of powder appears uniform, but at the microscopic level, it's a mixture of different particle sizes and distributions. One pinch of the sample is not necessarily representative of the whole. For a pharmaceutical blend or a geological sample, this heterogeneity can render an analysis dangerously misleading.

The Voids of Uncertainty

Air pockets are the natural enemy of precision. These tiny voids between particles scatter the energy beams—be it X-rays or infrared light—used in spectroscopic analysis. It's like trying to take a crystal-clear photograph through a foggy window; the final image is distorted and unreliable.

The Chaos of an Uneven Surface

An irregular powder surface is a hall of mirrors for an analytical instrument. It reflects and refracts energy inconsistently. The measurement you get is a game of chance, dependent on the exact spot the beam hits. This makes repeatable results virtually impossible.

Imposing Order: The Mechanics of Truth

This is where a laboratory hydraulic press enters the narrative. Its function is deceptively simple but profound: to apply immense, controlled force to transform a chaotic powder into a solid, uniform pellet.

It's an act of sculpting the perfect medium for analysis.

Forging Uniform Density

By applying thousands of pounds of pressure, the press systematically expels trapped air, forcing individual particles into intimate contact. The result is a solid pellet with a consistent, uniform density. Now, the analytical beam interacts with the same amount of material no matter where it probes, creating a reliable constant from a former variable.

Crafting the Perfect Surface

Inside a hardened steel die, the powder isn't just compressed; it's molded into a disc with a mathematically flat, smooth surface. This removes the "hall of mirrors" effect, providing a perfect, predictable target for the instrument's beam. Repeatability is no longer a goal; it's an engineered outcome.

The Spectroscopic Payoff: Two Case Studies

This transformation from powder to pellet has dramatic consequences in high-stakes analytical techniques.

Case Study 1: The XRF Challenge

- Goal: Determine the precise elemental composition of a sample.

- Problem: X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) is highly sensitive to "matrix effects"—errors caused by physical variations like surface roughness and density. A raw powder will yield inaccurate quantitative data.

- Solution: A pressed pellet presents a homogeneous surface to the X-ray beam. It minimizes matrix effects, ensuring the instrument reports the true elemental census of the material, not the noise created by its physical form.

Case Study 2: The FTIR Imperative

- Goal: Identify a material's internal chemical bonds.

- Problem: For solid samples, Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy often uses a KBr pellet. The sample is mixed with potassium bromide powder (which is transparent to infrared light) and pressed. If the resulting pellet is cloudy, cracked, or uneven, the IR beam cannot pass through cleanly.

- Solution: A hydraulic press creates a thin, perfectly translucent KBr pellet. It becomes a crystal-clear window, allowing the IR beam to pass through unimpeded to reveal the sample's true spectral fingerprint.

The Engineer's Prerogative: Precision and Control

The key is not just force, but controlled force. Too little pressure creates a fragile pellet that crumbles. Too much can fracture the sample or, in some cases, alter its crystalline structure. This delicate balance requires more than just brute strength; it requires precision.

This is where the design philosophy of modern laboratory presses becomes critical. Instruments like KINTEK's automatic and isostatic lab presses are engineered not just to apply force, but to apply the right force, repeatably and reliably. Advanced systems, such as their heated lab presses, offer even greater control for specialized applications. They transform the art of sample preparation into a robust science.

| Aspect | Raw Powder (The Chaos) | Pressed Pellet (The Order) |

|---|---|---|

| Density | Non-uniform, with air pockets | Homogeneous and consistent |

| Surface | Irregular and rough | Smooth, flat, and predictable |

| Repeatability | Low; results vary with each test | High; consistent and reliable data |

| Best For | Quick qualitative screening | Quantitative XRF, FTIR (KBr) |

Ultimately, the integrity of our most advanced analytical data is built upon the physical integrity of a simple pressed pellet. Achieving this foundational quality is the first step toward data you can trust. If your work demands precision and repeatability, ensuring your sample preparation is flawless is non-negotiable. Contact Our Experts

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

- Laboratory Hydraulic Split Electric Lab Pellet Press

Related Articles

- Beyond the Spec Sheet: The Unseen Infrastructure of a Laboratory Press

- The Unseen Variable: Why Your Lab Press Dictates Your Data's Integrity

- From Chaos to Cohesion: The Physics and Psychology of a Perfect Sample Pellet

- The Physics of Consistency: How Hydraulic Presses Overcome Human Error

- Beyond the Part Number: The Psychology of Sourcing Lab Press Components