The Anatomy of Failure

A jet engine turbine blade spins thousands of times per minute, enduring temperatures that would melt steel and forces that would tear lesser materials apart. Our trust in that engine, and in the aircraft it powers, is an act of faith in material science.

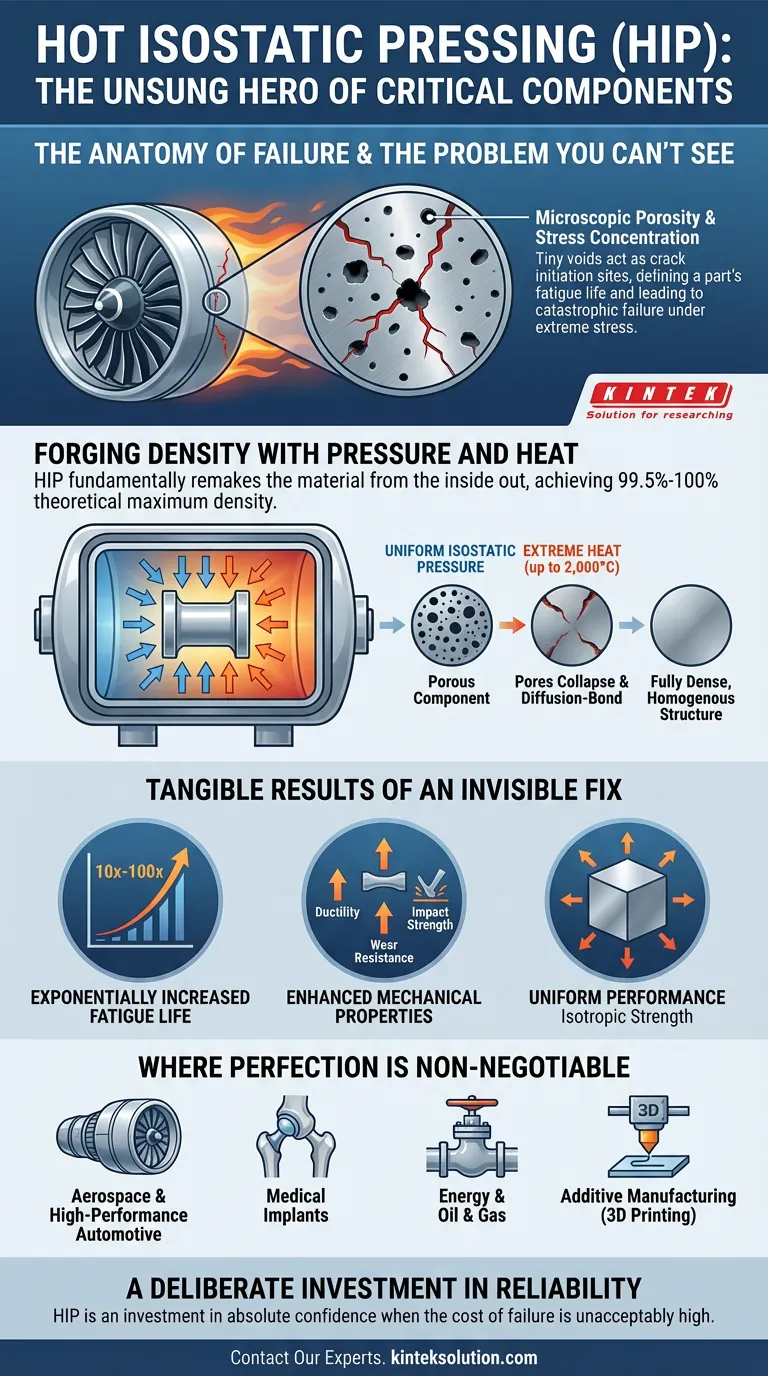

But the greatest threat to that blade isn't an external impact. It's a flaw you can't see—a microscopic void, an internal pore left over from its creation. Under immense stress, this invisible imperfection becomes the starting point for a catastrophic crack.

The psychology of engineering is often a battle against these unseen enemies. We design for strength and durability, but true reliability comes from conquering the flaws hidden deep within a material's structure.

The Problem You Can't See

Nearly every manufacturing process, from ancient casting to modern 3D printing, can create microscopic porosity. These tiny voids are like air bubbles trapped in a solid structure.

To the naked eye, the component looks perfect. But under stress, these pores concentrate forces, acting as leverage points for cracks to form and propagate. A part's fatigue life—its ability to withstand repeated cycles of stress—is dictated not by its overall strength, but by its weakest internal point.

This is the fundamental problem Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) was designed to solve. It doesn't just coat a surface or treat a part; it fundamentally remakes it from the inside out.

Forging Density with Pressure and Heat

The HIP process is an elegant display of physics. A component is placed inside a sealed, high-pressure vessel. The chamber is filled with an inert gas, typically argon, and heated to extreme temperatures, often approaching 2,000°C.

Then, immense pressure is applied—uniformly, from all directions.

This isostatic pressure squeezes the component, causing the material to plastically deform on a microscopic level. The internal voids and pores collapse and diffusion-bond, effectively welding themselves shut. The material is consolidated into a fully dense, homogenous structure.

The result is a component that achieves 99.5% to 100% of its theoretical maximum density. It is as close to a perfect solid as physically possible.

The Tangible Results of an Invisible Fix

Eliminating porosity doesn't just make a part heavier; it unlocks its true performance potential. The benefits are dramatic and measurable.

- Exponentially Increased Fatigue Life: With no internal crack initiation sites, a component's resistance to cyclical stress can increase by a factor of 10 to 100.

- Enhanced Mechanical Properties: Ductility, impact strength, and wear resistance are all significantly improved, creating a tougher, more reliable part.

- Uniform Performance: The material becomes isotropic, meaning its strength is consistent in all directions, free from the internal weak points that can cause unpredictable failures.

Where Perfection is Non-Negotiable

This pursuit of ultimate density explains why HIP is the standard in industries where failure is not an option.

Aerospace & High-Performance Automotive

For mission-critical turbine blades, engine discs, and structural airframe components, HIP is not a luxury; it's a necessity. It ensures parts can withstand extreme operational forces without succumbing to fatigue.

Medical Implants

An artificial hip or knee joint is designed to last for decades inside the human body. HIP is used to densify titanium and cobalt-chrome implants, removing the porosity that could lead to fracture and failure over a patient's lifetime. It's a process that underwrites our trust in medical technology.

Energy & Oil & Gas

Components in subsea valves, drilling equipment, and power generation turbines operate in brutally corrosive and high-pressure environments. HIP creates parts with superior durability and corrosion resistance, ensuring safety and operational longevity.

Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing)

HIP is a critical enabling technology for 3D-printed metal parts. The additive process inherently can leave porosity. HIP is the definitive post-processing step that transforms a 3D-printed component from a prototype into a high-performance, load-bearing part with properties that can exceed even traditional forgings.

A Deliberate Investment in Reliability

HIP is not a simple or inexpensive process. It involves specialized equipment and long cycle times. It cannot fix major manufacturing defects like surface cracks or foreign material inclusions—it is designed to perfect an already well-made part.

But viewing it through the lens of cost misses the point. The decision to use HIP is a psychological one. It's an investment made when the cost of failure—in financial, operational, or human terms—is unacceptably high. It is the price of admission for achieving absolute confidence in a critical component.

This journey towards flawless material integrity often begins in the lab, where new alloys and processes are validated. Developing reliable manufacturing protocols requires equipment that can precisely replicate these extreme conditions on a smaller scale. For researchers and engineers pushing these boundaries, having precise and reliable laboratory presses, including advanced isostatic and heated models, is the essential first step.

If you are ready to eliminate the invisible threats in your critical components, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Laboratory Split Manual Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

Related Articles

- The Unseen Variable: Why Controlled Force is the Foundation of Repeatable Science

- The Architecture of Strength: Mastering Material Microstructure with Hot Pressing

- Mastering Microstructure: Why Hot Pressing is More Than Just Heat and Pressure

- Clarity from Chaos: Mastering Sample Preparation for FTIR Spectroscopy

- Pressure Over Heat: The Elegant Brutality of Hot Pressing for Dimensional Control