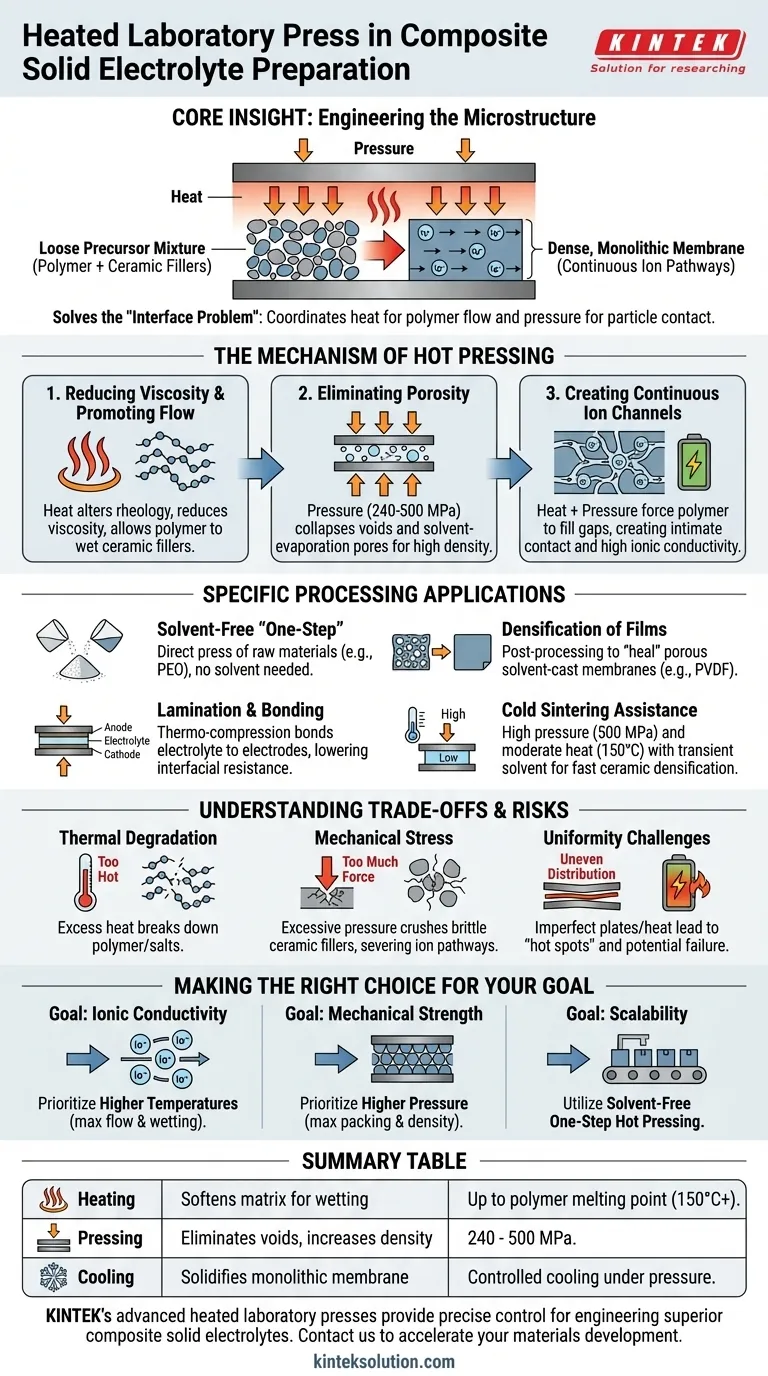

A heated laboratory press is the fundamental tool for transforming loose precursor materials into high-performance composite solid electrolytes. It operates by applying simultaneous thermal energy and mechanical force to a mixture of ceramic fillers and a polymer matrix. This dual action softens the polymer to reduce viscosity while compressing the material to eliminate voids, resulting in a dense, monolithic membrane with the continuous pathways necessary for ion transport.

Core Insight: The heated press does not merely shape the material; it engineers the microstructure. By coordinating heat to induce polymer flow and pressure to enforce particle contact, it solves the "interface problem"—ensuring the polymer matrix creates a seamless, void-free bond with conductive ceramic fillers.

The Mechanism of Hot Pressing

The preparation of composite electrolytes relies on balancing the mechanical properties of polymers with the conductive properties of ceramics. The heated press acts as the bridge between these two states.

Reducing Viscosity and Promoting Flow

The application of heat is critical for altering the rheology of the polymer matrix (such as PEO or PVDF).

By raising the temperature—often to the polymer's melting point or glass transition temperature—the press reduces the material's viscosity. This increases flowability, allowing the polymer to wet the surface of the inorganic ceramic fillers (like LLZTO or LATP) effectively.

Eliminating Porosity

Pressure is the primary driver for densification. Whether processing a dry powder mix or a solvent-cast film, internal voids act as barriers to ion movement.

The press applies significant force (often between 240 MPa and 500 MPa) to collapse these air bubbles and solvent-evaporation pores. This ensures that the final membrane is non-porous and physically dense.

Creating Continuous Ion Channels

For a composite electrolyte to function, ions must move freely between the polymer and the ceramic.

The combination of heat-induced flow and pressure-induced compaction forces the polymer to fill the microscopic gaps between ceramic particles. This creates intimate contact and continuous transport channels, which directly correlates to higher ionic conductivity.

Specific Processing Applications

The heated press is versatile and is used in several distinct fabrication methodologies depending on the materials involved.

Solvent-Free "One-Step" Preparation

For polymers like PEO, the heated press enables a solvent-free manufacturing route.

Raw materials (polymer, salts, fillers) are mixed and pressed directly. The heat melts the matrix to disperse components at a molecular level, while pressure forms a stable membrane in a single step, bypassing the need for solvent evaporation and recovery.

Densification of Solvent-Cast Films

In processes involving PVDF, a porous membrane is often initially formed via solvent evaporation.

The heated press is used as a post-processing step to "heal" the structure. It eliminates the large pores left by the evaporating solvent, inducing the polymer to flow and tightly bind the ceramic fillers into a cohesive sheet.

Lamination and Interfacial Bonding

Beyond forming the electrolyte itself, the heated press is used to integrate the electrolyte with electrodes.

Through thermo-compression, the press bonds the electrolyte layer securely to the anode or cathode. This lowers interfacial resistance and improves the overall mechanical stability of the battery cell.

Cold Sintering Assistance

In advanced ceramic composites (like LATP-Li₃InCl₆), the press facilitates "cold sintering."

By applying high uniaxial pressure (up to 500 MPa) at moderate temperatures (e.g., 150°C) with a transient solvent, the press accelerates dissolution-precipitation reactions. This achieves high densification typically associated with much higher temperatures in a fraction of the time.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While the heated press is essential, improper control of parameters can degrade the electrolyte performance.

Thermal Degradation Risks

Excessive heat can break down the polymer chains or degrade the lithium salts within the matrix. It is vital to operate within a temperature window that softens the polymer without compromising its chemical integrity.

Mechanical Stress on Fillers

While high pressure reduces voids, excessive force can crush brittle ceramic fillers. If the ceramic particles fracture, the ion transport pathways are severed, leading to increased impedance despite the high density of the pellet.

Uniformity Challenges

If the press platens are not perfectly parallel or the heat distribution is uneven, the electrolyte will have inconsistent thickness. This leads to "hot spots" of current density during battery operation, potentially causing dendrite formation and failure.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The specific settings you use on a heated press should be dictated by the limiting factor of your composite material.

- If your primary focus is Ionic Conductivity: Prioritize higher temperatures (within safety limits) to maximize polymer flow and wetting of the ceramic particles, ensuring minimal interfacial resistance.

- If your primary focus is Mechanical Strength: Prioritize higher pressure to maximize particle packing and density, creating a robust barrier against lithium dendrites.

- If your primary focus is Scalability: Utilize the press for solvent-free, one-step hot pressing to eliminate the complexities and drying times associated with wet chemistry methods.

Ultimately, the heated press is an instrument of interface engineering; its value lies in its ability to force two dissimilar materials into a unified, conductive whole.

Summary Table:

| Process Step | Key Function | Typical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Heating | Softens polymer matrix for better filler wetting | Temperature: Up to polymer melting point (e.g., 150°C+) |

| Pressing | Eliminates voids, increases density | Pressure: 240 - 500 MPa |

| Cooling | Solidifies the dense, monolithic membrane | Controlled cooling under pressure |

Ready to engineer superior composite solid electrolytes in your lab? KINTEK's advanced heated laboratory presses provide the precise control over temperature and pressure required to eliminate porosity and create continuous ion-conducting pathways. Whether your goal is maximizing ionic conductivity, mechanical strength, or scalable solvent-free production, our automatic lab presses, isostatic presses, and heated lab presses are designed to meet the demanding needs of battery research and development. Contact our experts today to discuss how our solutions can accelerate your materials development.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- 24T 30T 60T Heated Hydraulic Lab Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Manual Heated Hydraulic Lab Press with Integrated Hot Plates Hydraulic Press Machine

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

People Also Ask

- What role does a heated hydraulic press play in powder compaction? Achieve Precise Material Control for Labs

- How does using a hydraulic hot press at different temperatures affect the final microstructure of a PVDF film? Achieve Perfect Porosity or Density

- What is a heated hydraulic press and what are its main components? Discover Its Power for Material Processing

- What industrial applications does a heated hydraulic press have beyond laboratories? Powering Manufacturing from Aerospace to Consumer Goods

- Why is a heated hydraulic press considered a critical tool in research and production environments? Unlock Precision and Efficiency in Material Processing