At its core, when an X-ray or gamma-ray beam strikes a sample in an XRF spectrometer, it triggers a chain reaction at the atomic level. The incoming high-energy beam knocks an electron out of an atom's inner shell, creating a temporary vacancy. This unstable atom immediately corrects itself by pulling an electron down from a higher-energy outer shell, releasing a secondary, fluorescent X-ray in the process.

The crucial insight is that this entire process generates an elemental "fingerprint." The energy of the emitted fluorescent X-ray is unique to the specific element it came from, which is how an XRF spectrometer can precisely identify the composition of a material.

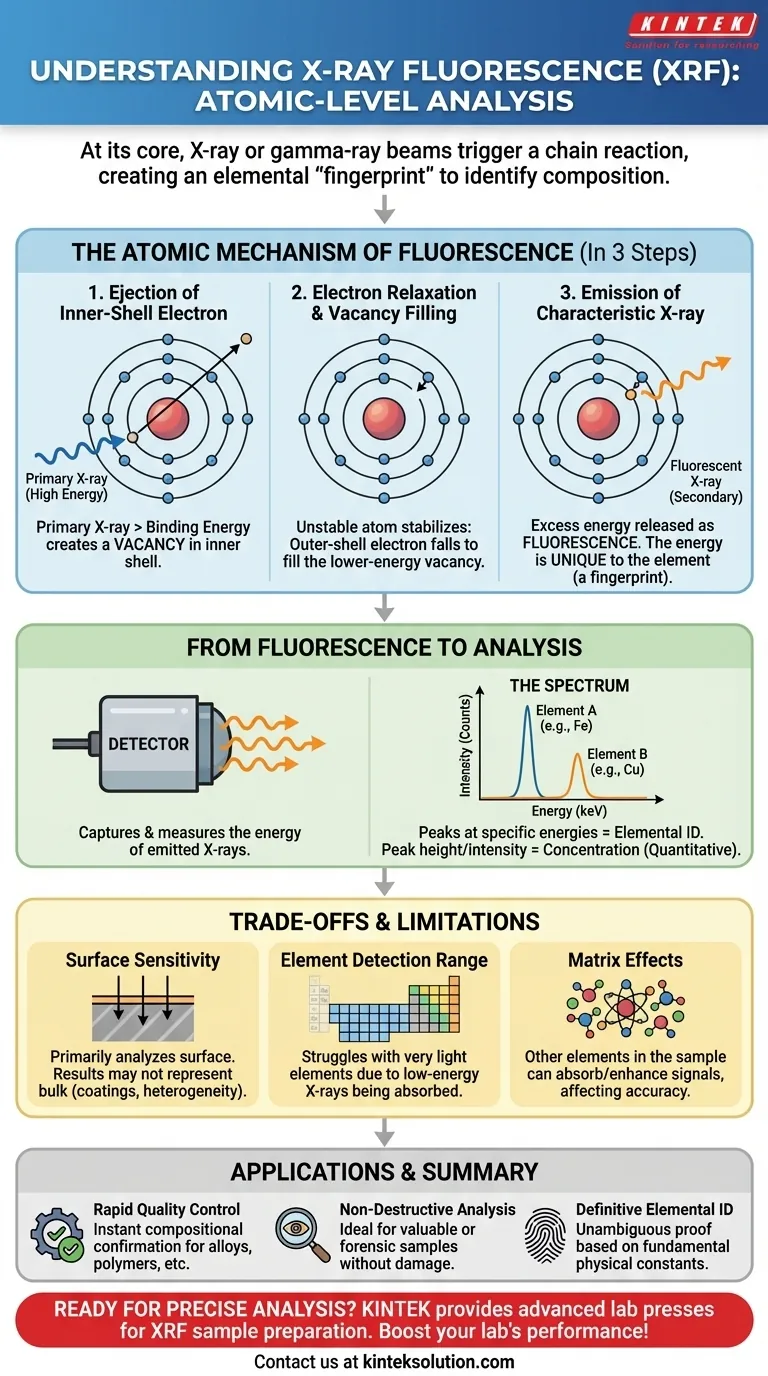

The Atomic Mechanism of Fluorescence

To understand how XRF identifies elements, we must look at the three distinct steps that occur within the sample's atoms in a fraction of a second.

Step 1: Ejection of an Inner-Shell Electron

The process begins when a high-energy X-ray from the spectrometer, known as the primary X-ray, collides with an atom in the sample.

For an interaction to occur, the energy of this primary X-ray must be greater than the binding energy of an electron in one of the atom's inner shells (typically the K or L shell).

When this condition is met, the energy is absorbed, and the inner-shell electron is ejected from the atom, creating a positively charged ion with an empty space, or vacancy.

Step 2: Electron Relaxation and Vacancy Filling

An atom with a vacancy in an inner electron shell is highly unstable. Nature seeks the lowest possible energy state to restore stability.

Almost instantaneously, an electron from a higher-energy outer shell (such as the L or M shell) "falls" to fill the vacancy in the lower-energy inner shell.

Step 3: Emission of a Characteristic X-ray

The electron that moved from the outer shell had a higher potential energy than the inner-shell electron it replaced. This excess energy cannot simply vanish.

The atom releases this energy difference as a new, secondary X-ray. This emitted X-ray is called fluorescence.

Critically, the energy of this fluorescent X-ray is not random. It is equal to the specific difference in energy between the two electron shells involved. Since every element has a unique electron shell configuration, this energy is a characteristic fingerprint of that element.

From Fluorescence to Analysis

The physical phenomenon of fluorescence is only the first part of the story. The spectrometer's genius lies in how it captures and interprets these elemental fingerprints.

The Role of the Detector

The spectrometer's detector is engineered to do two things: count the fluorescent X-rays leaving the sample and measure the precise energy of each one.

Building the Spectrum

As the detector measures the incoming fluorescent X-rays, it sorts them by their energy level. This data is plotted on a graph called a spectrum.

The spectrum displays peaks at specific energy values. Each peak corresponds directly to the characteristic fluorescent energy of a specific element present in the sample.

Why Concentration Matters

The intensity of the fluorescence—meaning the number of X-rays detected at a specific energy—is generally proportional to the concentration of that element in the sample.

A taller peak for iron, for example, indicates a higher concentration of iron than a shorter peak. This allows XRF to perform not just qualitative (what's in it?) but also quantitative (how much is in it?) analysis.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Limitations

While powerful, the principle of X-ray fluorescence has inherent limitations that every professional should understand.

Surface Sensitivity

XRF is primarily a surface-analysis technique. The fluorescent X-rays generated deep within a sample may be re-absorbed by other atoms before they can escape and reach the detector.

This means the results primarily reflect the composition of the sample's surface, which may not be representative of the bulk material if it is coated, corroded, or heterogeneous.

Element Detection Range

XRF struggles to detect very light elements (those with low atomic numbers, like hydrogen, lithium, or beryllium).

The characteristic X-rays produced by these elements have very low energy. They are often absorbed by the air between the sample and the detector or even by the detector's own protective window, making them effectively invisible.

Matrix Effects

The accuracy of quantitative analysis can be influenced by matrix effects. The "matrix" is everything else in the sample besides the element being measured.

These other elements can absorb or enhance the fluorescent signal of the target element, potentially skewing concentration results if not properly corrected for by the software.

How This Principle Is Applied in Practice

Understanding this atomic interaction allows you to know when to trust XRF for your specific goal.

- If your primary focus is rapid quality control: This atomic process is nearly instantaneous, providing immediate confirmation that a material (like a metal alloy or polymer) meets compositional specifications.

- If your primary focus is non-destructive analysis: This interaction only excites electrons and does not alter or damage the sample, making it ideal for testing valuable historical artifacts, finished products, or forensic evidence.

- If your primary focus is definitive elemental identification: The characteristic energy of the fluorescent X-ray is a fundamental physical constant, providing unambiguous proof of which elements are present in your sample.

By understanding this atomic interaction, you transform the XRF spectrometer from a black box into a predictable and powerful tool for material analysis.

Summary Table:

| Process Step | Key Action | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Ejection | Primary X-ray ejects inner-shell electron | Creates vacancy in atom |

| Electron Relaxation | Outer-shell electron fills vacancy | Atom stabilizes |

| Fluorescence Emission | Excess energy released as X-ray | Emits characteristic X-ray unique to element |

| Detection & Analysis | Detector measures energy and counts X-rays | Generates spectrum for qualitative and quantitative analysis |

Ready to enhance your laboratory's material analysis with precise, non-destructive testing? KINTEK specializes in advanced lab press machines, including automatic lab presses, isostatic presses, and heated lab presses, designed to support your XRF sample preparation and other lab needs. Our equipment ensures accurate, efficient results for quality control and research. Contact us today to learn how we can boost your lab's performance and reliability!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press 2T Lab Pellet Press for KBR FTIR

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Machine

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Press for XRF and KBR Pellet Pressing

- Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press Button Battery Press

- Manual Laboratory Hydraulic Press Lab Pellet Press

People Also Ask

- What role does a laboratory hydraulic press play in carbonate powder prep? Optimize Your Sample Analysis

- What role does a high-pressure laboratory hydraulic press play in KBr pellet preparation? Optimize FTIR Accuracy

- What is the role of a hydraulic press in KBr pellet preparation for FTIR? Achieve High-Resolution Chemical Insights

- Why must a laboratory hydraulic press be used for pelletizing samples for FTIR? Achieve Precision in Spectral Data

- Why use a laboratory hydraulic press with vacuum for KBr pellets? Enhancing Carbonate FTIR Precision