The Illusion of the Passive Agent

We have a deeply ingrained mental model for things like glue. We see it as a passive, sticky substance that simply "dries" to hold things together. Similarly, we might view a flux as just a simple cleaning fluid.

This is a profound misunderstanding.

In the world of precision manufacturing and material science, these substances are not passive fillers. They are active chemical agents that undergo transformation. The failure to appreciate their dynamic role is the root cause of countless bonding failures, from delaminated composites to faulty electronics.

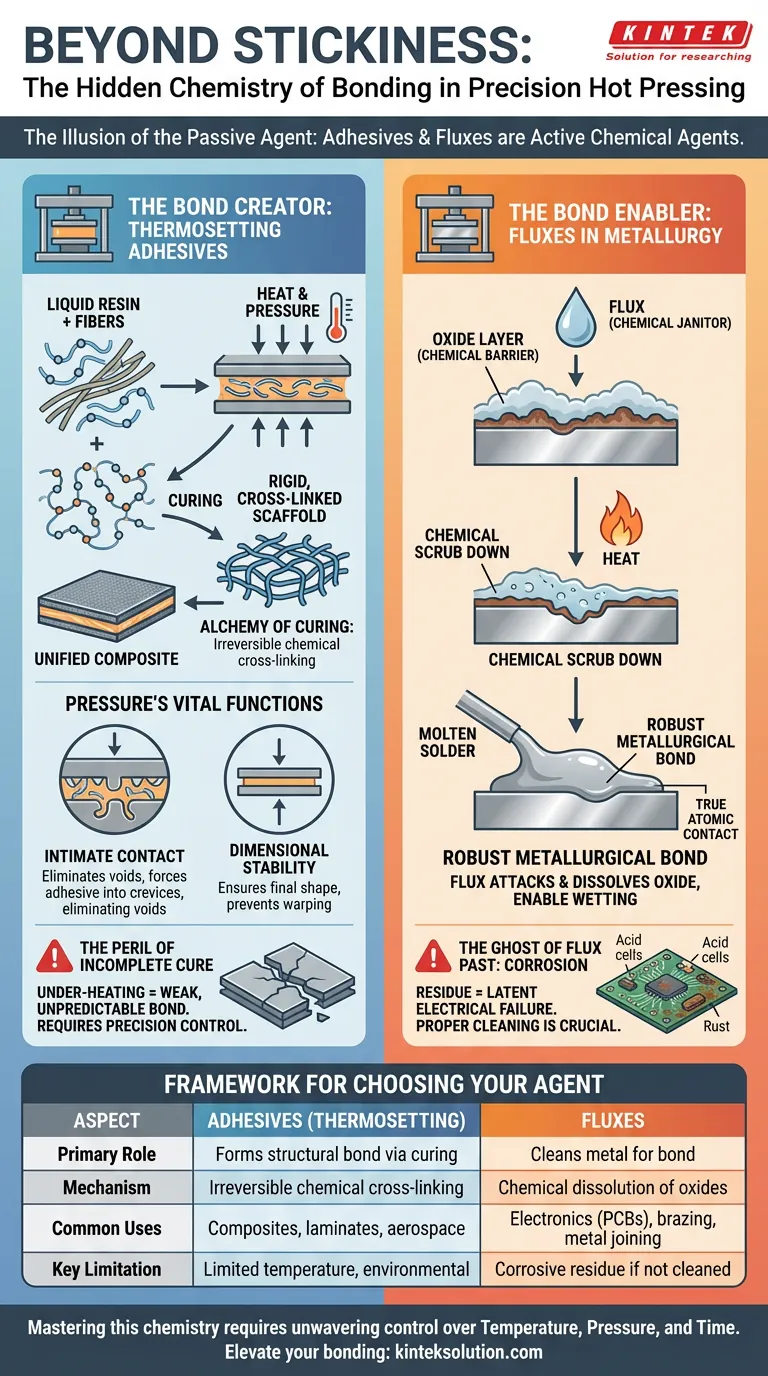

The critical distinction is this: adhesives create a new bond through a chemical reaction, while fluxes enable a metallurgical bond by preparing the surfaces. Understanding this difference is the first step to mastering the hot pressing process.

The Bond Creator: Thermosetting Adhesives

In technical applications, "glue" is a thermosetting adhesive—a polymer resin that performs a kind of alchemy under heat and pressure.

From Liquid to Solid: The Alchemy of Curing

Unlike a simple household glue that dries by evaporation, a thermosetting resin undergoes an irreversible chemical reaction called curing.

When a hot press applies heat, it energizes the polymer chains, causing them to cross-link and form a rigid, three-dimensional molecular scaffold. The liquid or semi-solid resin transforms into a hardened, structural solid.

Think of creating a high-strength aerospace component. The layers of carbon fiber fabric are initially flexible. The epoxy resin is just a viscous liquid. It is the precisely controlled environment of the hot press that forges them into a single, unified part that is often stronger and lighter than metal.

Pressure Is More Than Just a Squeeze

The pressure applied during hot pressing serves two vital functions that go beyond simply holding things in place:

- Intimate Contact: It forces the adhesive into every microscopic crevice of the substrates, eliminating voids. These tiny air pockets are the starting points for cracks and failures.

- Dimensional Stability: As the resin cures, pressure ensures the final part maintains its intended shape and uniform thickness, preventing warping or distortion.

The Bond Enabler: Fluxes in Metallurgy

Flux is not a bonding agent at all. It is a chemical janitor, and its job is one of the most important in electronics and metal joining.

The Invisible Enemy: Oxide Layers

Almost all useful metals, from copper on a circuit board to structural steel, instantly react with air to form a thin, invisible layer of oxide.

This oxide layer is a chemical barrier. It prevents a molten filler metal, like solder, from making true atomic contact with the base metal. Trying to solder an oxidized surface is like trying to shake hands while wearing thick gloves. The molten solder will bead up, refusing to "wet" the surface, resulting in a weak, unreliable joint waiting to fail.

The Chemical Scrub Down

When heated in a hot press, flux becomes chemically active. It aggressively attacks and dissolves the oxide layers, exposing the pure, raw metal underneath.

Now, when the solder melts, it can flow freely over the pristine surface, forming a robust and continuous metallurgical bond. The pressure from the press helps squeeze the molten solder into the joint, expelling the now-liquid, and lighter, flux. The bond doesn't contain flux; it exists because of the flux.

The Psychology of Failure: When Process Control Is Ignored

Bonding failures often stem from a psychological trap: treating the hot press like an oven and the additives like ingredients. In reality, the press is a reactor, and success depends on controlling the reaction with absolute precision.

The Peril of the Incomplete Cure

Under-heating an adhesive or cutting the cycle short doesn't just create a weaker bond; it creates an unpredictable one. The polymer may not fully cross-link, leaving a component that feels solid but will fail unexpectedly under thermal or mechanical stress. This is why commercial labs and R&D teams rely on precision heated lab presses, where temperature profiles, pressure ramps, and dwell times are not just settings—they are the guarantors of a complete chemical transformation.

The Ghost of Flux Past: Corrosion

The most insidious failure mode with flux is corrosion. If any active flux residue remains after soldering, it can absorb moisture from the atmosphere, creating a tiny, acidic electrochemical cell. This cell will slowly eat away at the metal joint, leading to a latent electrical failure weeks, months, or even years later. A device can pass every initial quality check, only to fail in the field because of a microscopic spot of leftover residue.

A Framework for Choosing Your Agent

The choice between an adhesive and a flux is determined entirely by your materials and your goal. The wrong choice is not an option.

- Goal: To bond polymers, wood, or fiber composites into a single structural part.

- Agent: A thermosetting adhesive (e.g., epoxy, phenolic resin).

- Goal: To join two metal surfaces using a low-temperature filler metal (solder).

- Agent: A flux to chemically clean the surfaces for wetting.

- Goal: To join pure metals or ceramics directly at high temperatures without a filler.

- Agent: Often none. This process, called diffusion bonding, may require a vacuum hot press to prevent oxidation from occurring in the first place.

This table summarizes the core differences:

| Aspect | Adhesives (Thermosetting) | Fluxes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Forms the structural bond itself via curing | Cleans metal surfaces to enable a bond |

| Mechanism | Irreversible chemical cross-linking | Chemical dissolution of metal oxides |

| Common Uses | Composites, laminates, aerospace, wood products | Electronics (PCBs), brazing, metal joining |

| Key Limitation | Limited service temperature, environmental factors | Corrosive residue if not properly cleaned |

Mastering this chemistry requires a tool that offers unwavering control over the core variables of temperature, pressure, and time. If you're ready to elevate your bonding applications from approximation to precision, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Lab Heat Press Special Mold

- Cylindrical Lab Electric Heating Press Mold for Laboratory Use

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine With Heated Plates For Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

- Laboratory Manual Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates

Related Articles

- The Internal Architecture of Strength: Why Hot Pressing Forges a New Class of Materials

- How to Choose a Laboratory Hot Press for Precise Material Processing

- The Alchemy of Force and Fire: Why Precision in Hot Pressing Defines Material Innovation

- Beyond Brute Force: The Subtle Art of Material Consolidation with Hot Pressing

- The Architecture of Strength: Mastering Material Microstructure with Hot Pressing