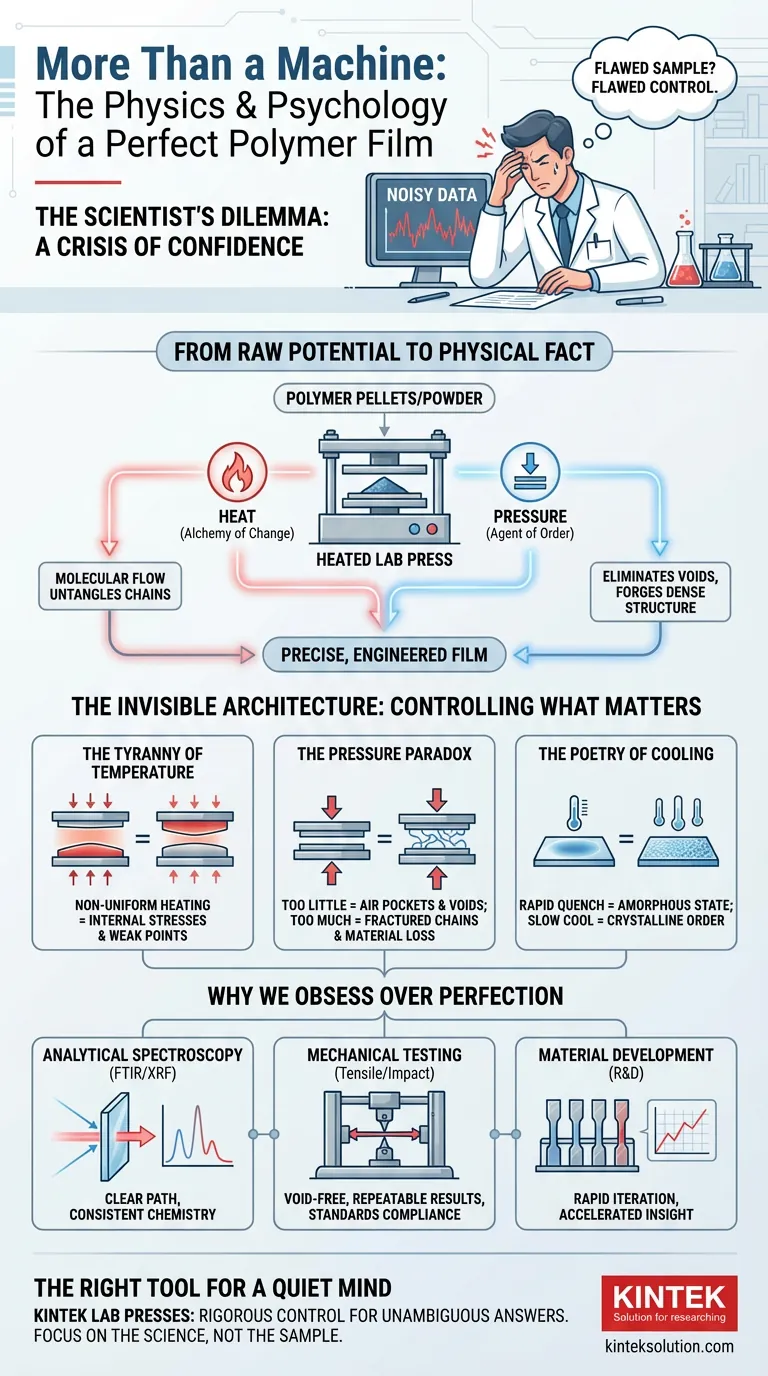

The Scientist's Dilemma: A Crisis of Confidence

Imagine a materials scientist staring at a spectrograph. The data is noisy, inconclusive. Months of research into a new polymer blend are jeopardized not by a flawed hypothesis, but by a flawed sample. The thin film, which should have been a perfect, uniform window into the material's soul, was warped by unseen stresses and microscopic voids.

This isn't a failure of chemistry. It's a failure of control.

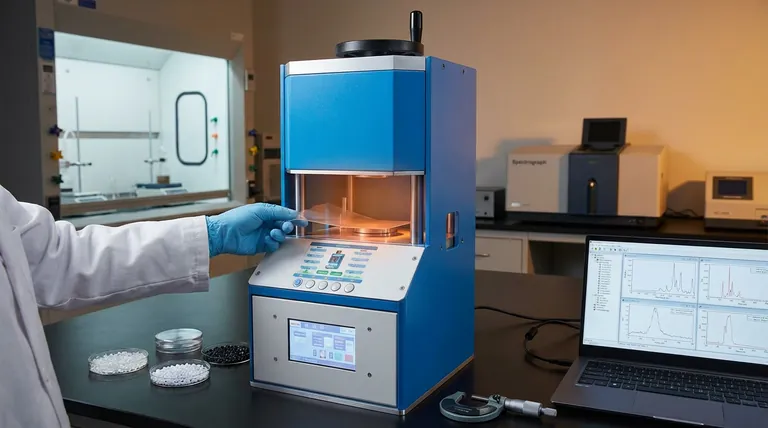

At its heart, research is the pursuit of certainty. We create controlled environments to isolate variables and test ideas. But what happens when the very tool meant to create your specimen introduces its own chaos? The heated lab press, a seemingly simple device, sits at this critical junction. Its job is not just to flatten plastic; it is to impose order on a molecular scale.

From Raw Potential to Physical Fact

A heated press works on a principle of brutal elegance: it uses heat and force to transform polymer pellets or powder into a precise, engineered film.

The Alchemy of Heat and Pressure

Heat is the agent of change. Applied through heated platens, it brings the polymer past its melting or glass transition temperature, allowing its long molecular chains to untangle and flow.

Pressure is the agent of order. As the press engages, it applies a uniform, immense force, compelling the molten material to fill every corner of a mold or spread evenly between two plates. This act eliminates voids and forges a dense, homogenous structure.

The result is not just a piece of plastic. It's a physical embodiment of a specific, intended state.

The Invisible Architecture: Controlling What Matters

The true artistry of using a heated press lies in managing the invisible. The final properties of the film—its strength, clarity, and chemical stability—are dictated by parameters that are felt but not seen.

The Tyranny of Temperature

The most common point of failure is non-uniform heating. If one part of the platen is a few degrees hotter than another, the polymer flows unevenly. This creates internal stresses and weak points—a hidden architecture of failure locked within the sample, rendering it useless for any serious mechanical testing.

The Pressure Paradox

Pressure must be applied with intention. Too little, and you get a sample riddled with air pockets, a sponge where you need a solid. Too much, and you risk physically fracturing the polymer chains or squeezing vital material out of the mold, altering the very composition you set out to test.

The Poetry of Cooling

Perhaps the most underrated variable is the cooling rate. A rapid quench freezes the polymer's amorphous, disordered state. A slow, controlled cool allows molecules the time to arrange themselves into ordered crystalline structures. This single choice—how quickly you remove energy from the system—can radically change a material's tensile strength and optical properties. It is the difference between chaos and crystallinity.

Why We Obsess Over Perfection

The films produced in a lab press are rarely the final product. They are intermediaries—highly controlled specimens created for one purpose: to yield unambiguous answers.

-

For Analytical Spectroscopy (FTIR/XRF): A beam of light or X-ray needs a clear, consistent path. A uniform film provides this, ensuring the resulting spectrum reflects the material's chemistry, not the sample's imperfections.

-

For Mechanical Testing (Tensile/Impact): To trust the data, the sample must be a perfect representation of the material. A void-free, uniformly dense specimen that meets international standards (like those for PE, PP, or ABS) ensures your measurements are valid and repeatable.

-

For Material Development: In R&D, a lab press becomes an engine of discovery. It allows researchers to rapidly iterate, creating small test samples of new formulations to see how processing conditions affect final properties. It accelerates the cycle from idea to insight.

| Parameter | The Goal: Control | The Risk: Chaos |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Uniform heat for consistent molecular flow | Internal stresses, weak points, non-uniform thickness |

| Pressure | Void-free, uniform density | Incomplete compaction or physical polymer damage |

| Dwell Time | Complete melting and material distribution | Inhomogeneous structure, unmelted particles |

| Cooling Rate | Dictates crystallinity and microstructure | Unintended mechanical or optical properties |

The Right Tool for a Quiet Mind

The pursuit of perfect data demands a tool that eliminates variables, a machine that executes your intent with flawless precision. This is why the quality of your lab press is paramount. It's not about convenience; it's about confidence in your results.

KINTEK's range of automatic and heated lab presses are engineered for this exact purpose. They provide the rigorous control over temperature uniformity, pressure application, and cooling protocols that modern research demands. By removing the uncertainty from sample preparation, they allow you to focus on the bigger questions—confident that the material in your hand is the material you designed.

To remove the variable of inconsistent sample preparation from your work, Contact Our Experts

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- 24T 30T 60T Heated Hydraulic Lab Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Lab Heat Press Special Mold

- Cylindrical Lab Electric Heating Press Mold for Laboratory Use

Related Articles

- The Quiet War on Voids: Achieving Material Perfection with Hot Pressing

- Clarity from Chaos: Mastering Sample Preparation for FTIR Spectroscopy

- Pressure Over Heat: The Elegant Brutality of Hot Pressing for Dimensional Control

- The Tyranny of the Void: Why Porosity Is the Unseen Enemy of Material Performance

- Beyond Tonnage: The Subtle Art of Specifying a Laboratory Press