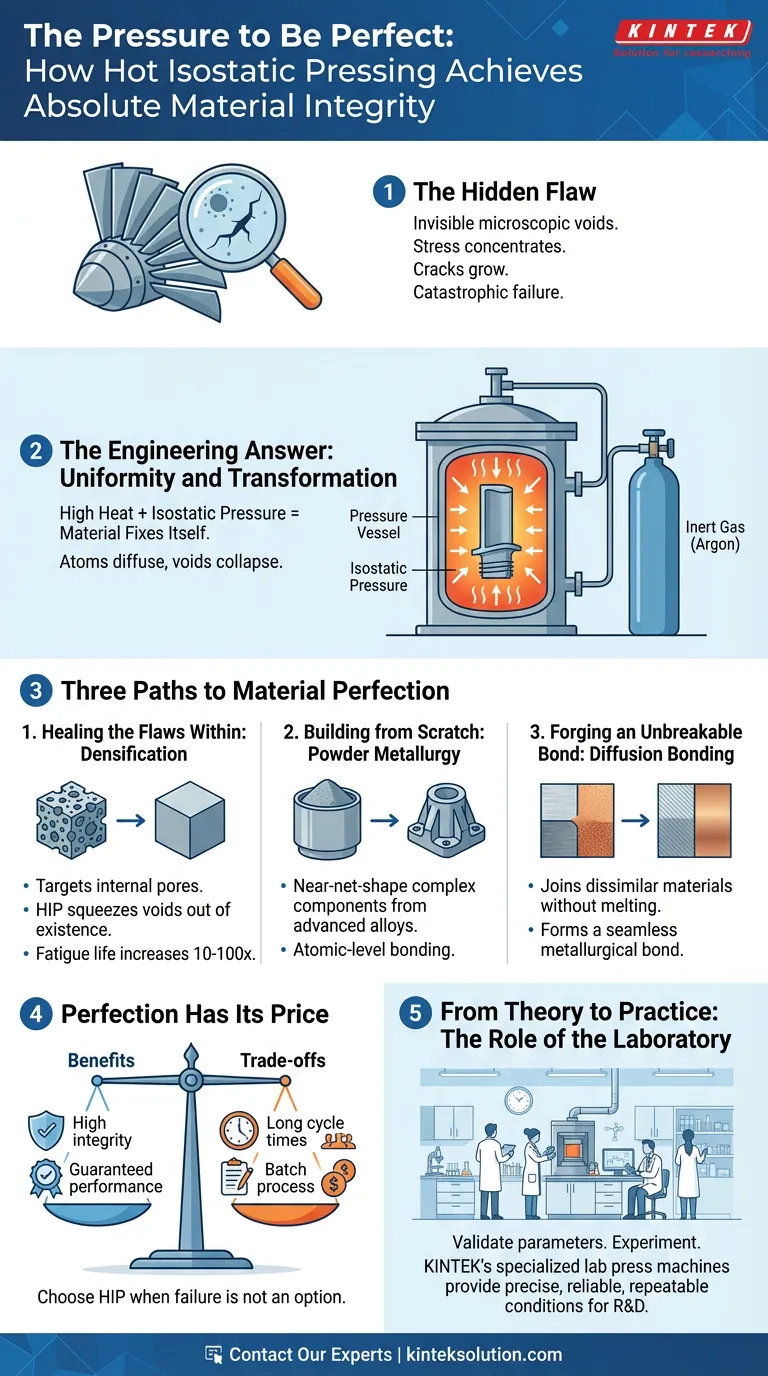

The Hidden Flaw

Imagine a turbine blade in a jet engine, spinning thousands of times per minute under immense heat and stress. Deep inside the superalloy, invisible to any surface inspection, lies a microscopic void—a tiny bubble of empty space left over from the casting process.

For millions of cycles, it's harmless. But with every rotation, stress concentrates at the edges of this void. Slowly, a crack begins to grow. The failure isn't a matter of if, but when.

This scenario is the engineer's nightmare. It’s a battle against an invisible enemy: the inherent imperfections hidden within a material. It’s why the pursuit of "good enough" often falls short, and why a different philosophy is required for components where failure is not an option.

The Psychology of Certainty

Engineers are trained to be rational, but the drive for material perfection is deeply psychological. It’s about achieving certainty in an uncertain world.

When a component's failure could be catastrophic, we can no longer rely on statistical averages. We need to know that every single part is as close to its theoretical perfection as possible.

This isn't just about over-engineering; it's about fundamentally changing the material itself. It's about removing the element of chance.

The Engineering Answer: Uniformity and Transformation

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) is the answer to this challenge. It is less a manufacturing step and more a transformative process.

The mechanism is elegant in its simplicity. A component is placed inside a high-pressure vessel. The vessel is heated to elevate the material's temperature, reducing its strength and making it more pliable. Then, a high-purity inert gas, usually argon, is pumped in, creating immense, perfectly uniform—or isostatic—pressure from all directions.

This combination of heat and pressure persuades the material to fix itself.

Three Paths to Material Perfection

HIP operates on three primary functions, each targeting a different form of material integrity.

1. Healing the Flaws Within: Densification

The most common use of HIP is to heal the microscopic voids that plague castings, forgings, and even 3D-printed metal parts.

- The Problem: Internal pores and voids act as stress concentrators, becoming the starting points for fatigue cracks.

- The HIP Solution: The isostatic pressure physically collapses these internal voids, squeezing them out of existence. Atoms diffuse across the former gap, creating a solid, uniform structure.

The result is a dramatic improvement in mechanical properties. Fatigue life can increase by a factor of 10 to 100. Ductility and fracture toughness are significantly enhanced. The material is not just repaired; it is reborn with a density approaching its theoretical maximum.

2. Building from Scratch: Powder Metallurgy

What if you could build a complex component with a perfect internal structure from the very beginning? This is the promise of HIP for powder metallurgy.

- The Method: Fine metal or ceramic powders are sealed in a container, or "canister," that is shaped like the final part.

- The Transformation: Inside the HIP vessel, the heat and pressure cause the individual powder particles to bond and fuse at an atomic level, forming a fully dense, solid component.

This near-net-shape manufacturing allows for intricate geometries from advanced alloys that would be impossible or prohibitively expensive to machine. It is atomic-level construction, ensuring a homogenous microstructure from the core to the surface.

3. Forging an Unbreakable Bond: Diffusion Bonding

Some applications require the best of two different materials—for instance, a tough, inexpensive core cladded with a highly corrosion-resistant outer layer. Welding can create such parts, but the intense heat creates weak, compromised zones.

- The Challenge: Joining dissimilar materials without melting them and altering their carefully engineered properties.

- The HIP Advantage: HIP facilitates solid-state diffusion bonding. At elevated temperatures, but below their melting points, atoms from the two surfaces intermingle. They form a true metallurgical bond that is as strong, or stronger, than the parent materials themselves.

There is no heat-affected zone, no structural compromise—only a seamless, perfectly integrated bimetallic component.

Perfection Has Its Price

This level of integrity comes with trade-offs. HIP is a batch process with long cycle times, making it unsuitable for high-volume, low-cost manufacturing. The equipment is specialized, and the high-purity powders required for powder metallurgy can be expensive.

But to view HIP through the lens of cost alone is to miss the point. You don't choose HIP to save money. You choose it when the cost of failure is infinitely higher.

From Theory to Practice: The Role of the Laboratory

Before committing to a full-scale industrial HIP cycle, material scientists and process engineers must ask critical questions. What is the optimal temperature? How much pressure is needed? How long should the cycle run for this specific alloy?

Answering these questions requires rigorous, controlled experimentation. This is where the laboratory becomes the birthplace of perfection.

Developing and validating the parameters for densification, powder consolidation, or diffusion bonding starts on a smaller scale. This is where KINTEK's specialized lab press machines become essential. Our automatic, isostatic, and heated lab presses provide the precise, reliable, and repeatable conditions necessary to pioneer new materials and perfect manufacturing processes. They are the tools that bridge the gap between theoretical potential and tangible, reliable performance.

Ultimately, HIP is a statement—a commitment to absolute integrity. When you need to guarantee performance and eliminate the possibility of hidden flaws, the journey begins with foundational research and development.

To explore how the right laboratory equipment can unlock the potential of your materials, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

- Laboratory Split Manual Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

Related Articles

- Beyond Tonnage: The Subtle Art of Specifying a Laboratory Press

- Pressure Over Heat: The Elegant Brutality of Hot Pressing for Dimensional Control

- The Unseen Variable: Why Controlled Force is the Foundation of Repeatable Science

- The Platen's Paradox: Why Bigger Isn't Always Better in Laboratory Presses

- The Internal Architecture of Strength: Why Hot Pressing Forges a New Class of Materials