The Illusion of Perfection

An aerospace engineer inspects a turbine blade. A surgeon handles a ceramic implant. To the naked eye, these objects are the definition of solid—flawless, uniform, and strong.

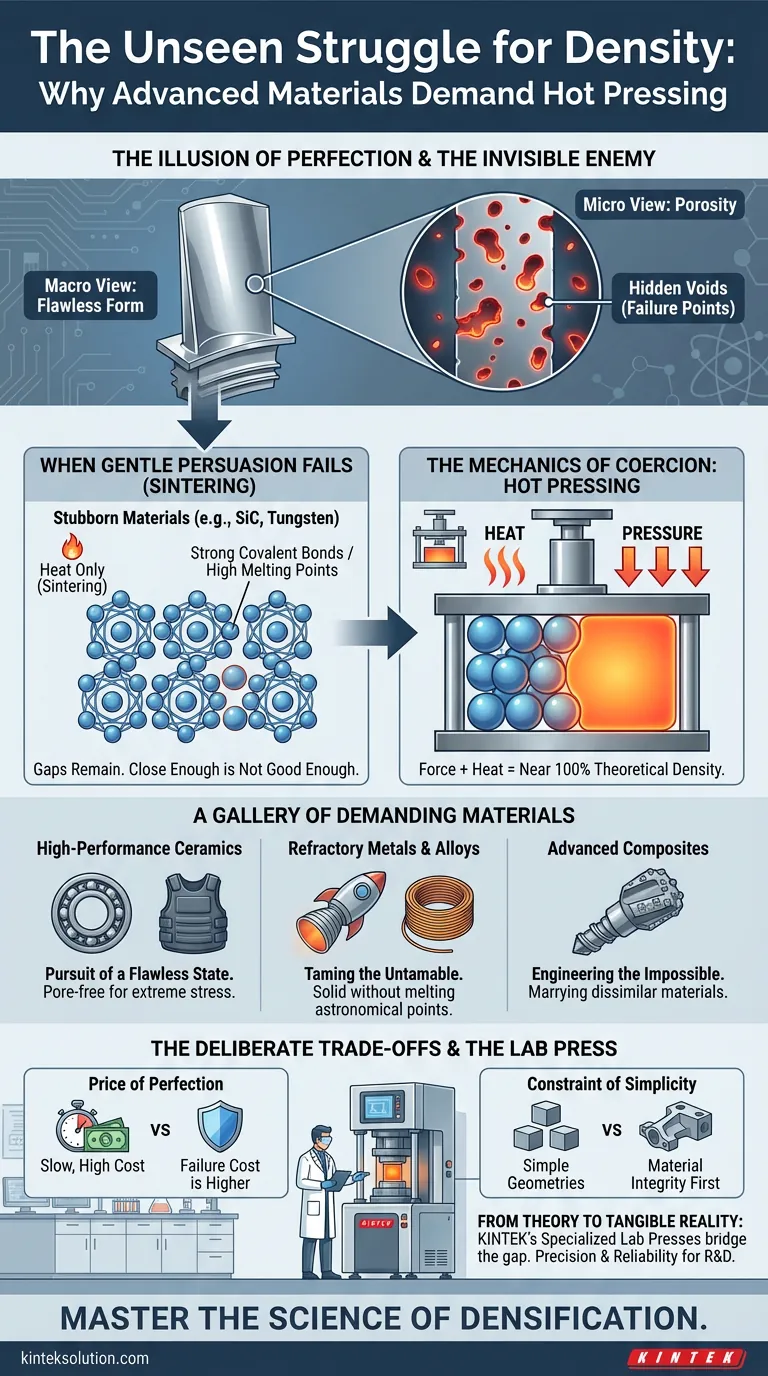

Our minds have a bias for the whole. We see a finished component and assume its internal structure is as perfect as its external form. But at the microscopic level, a battle has been waged against an invisible enemy: porosity. Voids, even minuscule ones, are the starting points for catastrophic failure.

The central challenge of modern materials science is that our most advanced materials—the strongest, hardest, and most heat-resistant—often resist becoming truly solid.

When Gentle Persuasion Fails

Traditional manufacturing, like sintering, is an act of persuasion. You take a powdered material, heat it below its melting point, and wait for atomic diffusion to gently coax the particles together, closing the gaps between them. For many materials, this works beautifully.

But high-performance materials are not easily persuaded.

- High-Performance Ceramics (like Silicon Carbide) have incredibly strong covalent bonds. Their atoms are locked in place and refuse to move.

- Refractory Metals (like Tungsten) have such high melting points that the temperatures required for effective sintering are extreme and impractical.

Sintering these materials is like asking a crowd of stubborn individuals to huddle together for warmth. They might get a little closer, but gaps will remain. For applications where failure is not an option, "close enough" is not good enough.

This is where persuasion gives way to force.

The Mechanics of Coercion: Hot Pressing

Hot pressing applies simultaneous high temperature and high pressure. The heat makes the material just pliable enough, and the immense, direct pressure mechanically forces the particles together, eliminating voids through plastic deformation and particle rearrangement.

It's no longer a suggestion; it's a command. The result is a component that is as close to 100% of its theoretical density as physically possible. This isn't a brute-force factory process; it's a precise, controlled operation often perfected in a laboratory setting to unlock a material's ultimate potential.

A Gallery of Demanding Materials

The decision to use hot pressing is driven by the material's inherent difficulty and the application's non-negotiable demand for performance.

High-Performance Ceramics: The Pursuit of a Flawless State

For silicon nitride (Si₃N₄) in ball bearings or silicon carbide (SiC) in body armor, internal voids are fatal flaws. Hot pressing is the only reliable way to create a fully dense, pore-free ceramic structure that can withstand extreme mechanical stress without fracturing.

Refractory Metals & Alloys: Taming the Untamable

Materials like tungsten and molybdenum are prized for their performance at temperatures that would turn steel into liquid. Hot pressing, as a form of powder metallurgy, allows us to consolidate these metal powders into solid, near-net-shape parts without having to reach their astronomical melting points.

Advanced Composites: Engineering the Impossible

Hot pressing excels at being a "marriage broker" for dissimilar materials. Consider a diamond-metal cutting tool. The process can consolidate a metal powder matrix around industrial diamond particles, creating a composite tool with a hardness and durability that neither material could achieve on its own.

The Deliberate Trade-Offs

Hot pressing is a specialist's tool, and its power comes with clear, intentional trade-offs. Choosing it is a strategic decision, not a default.

- The Price of Perfection: It is a slow, batch-based process with high energy costs. You don't choose hot pressing to save money on a part. You choose it because the cost of failure is infinitely higher.

- The Constraint of Simplicity: The uniaxial pressure typically limits designs to simple geometries like discs, blocks, or cylinders. This isn't a weakness; it's a creative constraint that forces engineers to focus on perfecting a component's material integrity over its geometric complexity.

From Theory to Tangible Reality: The Laboratory Press

These material breakthroughs don't happen on a production line. They are born from countless hours of experimentation in a research and development lab.

Scientists must test new formulations, fine-tune process parameters, and create prototypes to validate performance. This is where the precision and reliability of the equipment become paramount. The gap between a theoretical new material and a real-world component is bridged by the quality of the lab press.

For the materials scientists and engineers on this frontier, tools like KINTEK's specialized lab presses—from automatic and heated presses to isostatic systems—are the critical instruments. They provide the controlled environment needed to transform stubborn powders into the high-density, high-performance materials of the future.

Ultimately, hot pressing is more than a manufacturing process. It is a direct response to the defiance of our most capable materials. It is the focused application of force and heat to achieve a state of near-perfect density.

Whether you are developing next-generation transparent armor or pioneering novel metal-matrix composites, mastering the process is everything. If you're ready to master the science of densification, Contact Our Experts.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates for Laboratory

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

- Laboratory Split Manual Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Hot Plates

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine With Heated Plates For Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Certainty: How Hot Pressing Controls Material Perfection

- The Internal Architecture of Strength: Why Hot Pressing Forges a New Class of Materials

- Beyond the Furnace: How Direct Hot Pressing Reshapes Materials Research

- The Architecture of Strength: Mastering Material Microstructure with Hot Pressing

- Beyond Tonnage: The Subtle Art of Specifying a Laboratory Press